Our editors on the exhibitions they’re looking forward to this month, from a radical archive of LGBTQ+ experience in Brazil to the Bangkok Art Biennale

A Memorial for Catherine Christer Hennix (1948–2023)

Performance Space, New York, 9 November

Members of the Kamigaku Ensemble – a group led by the late Swedish musician and composer Catherine Christer Hennix – will perform her final work, Kamigaku, as part of an all-day sound program dedicated to this icon of drone music. Kamigaku is a durational composition featuring trumpets and the shō, a handheld Japanese mouth organ consisting of seventeen bamboo pipes. At Performance Space New York, it will be activated by Ellen Arkbro, Amir ElSaffar, Mattias Hållsten, Marcus Pal and Amedeo Maria Schwaller in an event marking the anniversary of Hennix’s passing, co-presented by Performance Space and the Brooklyn-based nonprofit Blank Forms, which has been compiling and releasing selections from Hennix’s archive since 2018. Notably, Kamigaku will proceed in accordance with an ethical principle Hennix developed in the 1970s – a time that saw her collaborating with the likes of Le Monte Young and Henry Flynt in the downtown New York art scene, teaching logic and math at MIT and SUNY New Paltz, respectively, and leading the just intonation band The Deontic Miracle, which played a single show at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm – that musicians ‘should be allowed unrestricted space and time’ to ‘play (only) when they feel inspired and (only) for as long as they feel inspired’. Jenny Wu

Arquivo Queer Br

Casa do Povo, São Paulo, through 16 November

In an unassuming residential district of São Paulo, Acervo Bajubá was founded in 2010. It is a small but densely-packed, growing library of archival materials relating to the LGBTQ+ experience in Brazil, historically and today. There are pamphlets, underground zines, newspapers, records, cassette tapes, theatre programmes and protest literature. On one shelf sits a complete collection of Cassandra Rios’s books, author of lesbian erotica, the first Brazilian to sell over one million copies, despite also being the country’s most censored writer. Some of this treasure has been moved temporarily to Casa do Povo, the radical-left Jewish centre in São Paulo’s downtown for an exhibition curated by one of Acervo Bajubá’s researchers, Angel Natan, and Matheus dos Reis of the OtherNetwork, an international coalition of off-spaces. Items include a poster for the first mass meeting of gay men in 1990 amid the AIDS crisis; the ID card of Neon Cunha, the first trans woman to officially change her name and gender without a medical certificate; and copies of Lampião and Femme, publications aimed at LGBTQ+ Brazilians. The archival material is contextualised with work by Natan herself and sculptors Paulo Assis, as well as historical work by Caetano de Almeida, Dora Longo Bahia, Félix González-Torres and Luiz Schwanke pulled from private collections by Reis. Oliver Basciano

The Living End: Painting and Other Technologies, 1970–2020

MCA Chicago, 9 November 2024 – 23 March 2025

‘Stupid like a painter,’ was Marcel Duchamp’s snooty opinion of artists who daubed paint on canvas without stopping to think too much about what they were doing. But this didn’t stop Duchamp from turning out his own archly ironic and theoretically self-aware paintings, and, by doing so, arguably turned painting into a much more conceptual endeavour ever since, in which painters have grappled with what kind of ‘technology’ – or what kind of image-making practice – painting might still be. MCA Chicago’s rangy group show takes on how artists since the 1970s have rethought painting even when the rise of mechanical image-making was supposed to have meant the ‘death of painting’. As it turned out, painting was both something you could blow up beyond its old boundaries (look out for Carolee Scheenman’s performance-installation 1971 Up to and Including Her Limits, where the artist dangled on a harness reaching out to mark canvases almost out of her reach, while mocking the macho gesturing of the earlier abstract expressionists); or a way to reflect on the status of screen-based mass culture, while absorbing its new technologies into painting – see Miriam Shapiro using early 3D rendering computing as the basis for her hard-edged geometries, or Warhol’s often overlooked mid-80s Amiga digital paintbox screen-monitor ‘paintings’. After all, who really needs brushes, when the all-encompassing ubiquity of digital culture means that younger artists are now effortlessly incorporating digital processes into the making of paintings? Take Petra Cortright’s Photoshopped concoctions of painterly motifs, printed direct to aluminium, or Avery K Singer’s sketchup rendered airbrush canvases of CGI painter-avatars hard at work in the studio. Old ideas about touch, mark-making and self-expression may be long dead, but as The Living End seeks to show, painters have found there’s a lot more for pigment on canvas still to do. J.J. Charlesworth

Rita Mawuena Benissan: One Must Be Seated

Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, 13 November 2024 – 5 October 2025

Born in Côte d’Ivoire to Ghanaian parents and raised in the US, Rita Mawuena Benissan’s practice travels in two simultaneous directions. She looks backwards, as a vocal and engaged activist in the African cultural heritage restitution movement, believing that you need to see your history to know – and be empowered – by it. And she faces forwards with artmaking across sculpture, tapestry and digital media that conjures an aesthetic of West African identity informed by an imagining of what it, re-empowered, might look like. One Must Be Seated centres the Akan people and their chieftain tradition of the royal umbrella and stool. Each room captures a stage in the process: the titular film of the exhibition introduces you to the tradition of a chief’s enstoolment, or coronation. An embroidered tapestry, We Process at Sunrise (2024) depicts an Akan palace at dusk, Benissan’s deep-ridged technique blurring the image as in a photograph or memory; while in the latest in her series of umbrella-works, each ornate velvet-canopy is embroidered with icons and patterning. Nothing here is simulating realness; Benissan acts as interlocutor between tradition, the preservation of which is perennially under threat, and modernity, an irrepressible idea forced on the continent by coloniality. In the final room, a lightly-embossed throne awaits, empty, spotlit in the dark. Alexander Leissle

Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gerome

Mathaf, Doha, through 22 February 2025

Jean-Léon Gérôme’s paintings can be found in many places, including on the cover of the first edition of Edward Said’s 1978 Orientalism – his Snake Charmer (1879) shows a teenage boy performing with a serpent coiled around his naked torso, watched by Islamic tribesmen sitting in front of an ornately tiled wall. Gérôme’s painting is fastidiously – and misleadingly – naturalistic, which would have made his painting look realistic and truthful. But the event is purely imaginary, and (although the architecture is based on a photograph of Topkapi Palace in modern-day Istanbul) the artist took the liberty of making up parts of the Arabic calligraphy depicted on the wall for aesthetic purposes. In the end Said tells us that Orientalist works show not so much about the Eastern world but were largely about the West and its desire to fetishise and dominate the ‘Orient’. It is remarkable then that Gérôme will be showing in Qatar. Comprising three sections that explore the artist’s life, his use of photography and contemporary reflections on his legacy, Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme will be presenting nearly 400 works gathered from the large collection of Orientalist painting owned by the Lusail Museum (the show’s organiser), as well as the collections of international museums. New commissions by Babi Badalov and Nadia Kaabi-Linke will also feature. Gérôme’s paintings will be examined against the Négritude movement and Iraqi modernist work such as Jewad Selim’s A Portrait of Lorna Selim (1948). Together the exhibition sees Orientalism as a product of colonialism – but one that can ‘motivate productive debate about old and new power structures and forms of identity’. It answers a question posed by the Lusail Museum: ‘how can Orientalist art be presented today, in a museum in the Arab world?’ Yuwen Jiang

Bruno Zhu: License to Live

Chisenhale Gallery, London, 22 November 2024 – 2 February 2025

The global circulation of mass-produced goods underpins the intimate, playful work of Portuguese artist Bruno Zhu, for whom the often-unthinking design of seemingly unremarkable spaces and objects in modern life has much to reveal about taste, consumption and power. Zhu, who has a background in fashion design, is all-too familiar with how design trends have a tendency to strip away context both historic and geographical, from the European craze for Chinoiserie in the 18th century to the factory reproduction of ornate willow-patterned plastic plates destined for mass retail in the 21st century. For over a decade Zhu has invited international artists to stage exhibitions at A Maior, the home furnishings and clothing store run by his parents in Viseu, Portugal; with each exhibition situated among the stationery, plant pots and toys, the latent hierarchies of culture and commerce are set idiosyncratically (at times uncomfortably) in situ. In License to Live, this provocative outlook is turned to a written licence agreement in which Zhu details a guide to the design of the exhibition, covering paint colour, flooring, ornamentation including bows to be tied around objects, and elaborate wall mouldings. A reflection on the authorship and agency of the artist, the licence brings to the fore the often-overlooked aspects of spatial display when it comes to the presentation not only of art but of products for sale. Conversely, each room of the gallery will remain empty of objects for the duration of the exhibition. Subsequent iterations of the show at other institutions will take on the same agreeement, with new artworks gradually introduced by Zhu into each restaging of the design as it morphs and takes on a life of its own – much like the endless stream of imports and exports shaping the global market today. Louise Benson

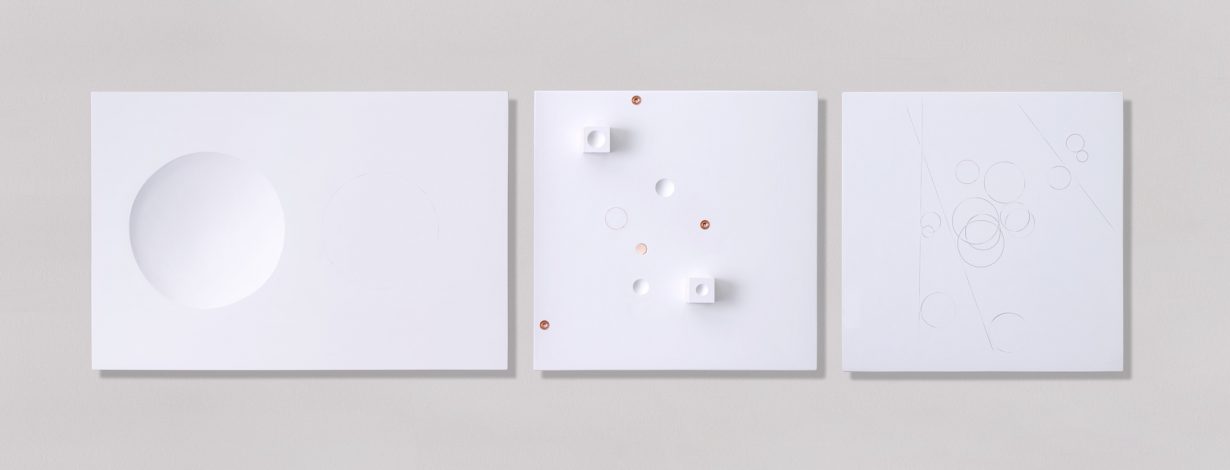

Prabhavathi Meppayil

Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, 12 November–21 December

Born to a family of goldsmiths spanning multiple generations, Prabhavathi Meppayil has taken the traditions of her ancestors and put them to use in the construction of something completely different: a painterly minimalism. The Bangalore-based artist creates her works by using a traditional thinnam (a goldsmithing tool), which she presses into white paint to create indents. Sometimes these marks stand out; sometimes they are almost imperceptible. But God is very much in the details here. It’s as if a bird or an insect had walked across some freshly poured concrete but did so with a sense of purpose. The results appear both static and active, vibrating curiously between their two- and three-dimensional properties. And these properties are only enhanced in works (such as m/twenty-three, 2024) that push the sculptural possibilities further with the inclusion of found objects and white cubes into Meppayil’s customary gesso surfaces. It’s proof, if you like, that ‘traditional’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘unchanging’. On the subject of which, this is the artist’s first solo show in Mumbai for 16 years. Nirmala Devi

SOUTH WEST BANK – Landworks, Collective Action and Sound

Palazzo Contarini Polignac, Venice, through 24 November

For those catching the final weeks of the Biennale, South West Bank is an archive of sorts, capturing actions and artworks made in the Palestine’s West Bank. The exhibition of 18 artists predominantly makes use of photography and film to act as documentary testaments to Palestinian lives. The large black and white photos of Adam Broomberg with Rafael González’s Anchor in the Landscape (2022) capture writhing, gnarled trunks of ancient olive trees, while Jumana Manna’s ambulatory, quietly seething film Foragers (2022) follows people who attempt to pick wild thyme and artichoke that grows in the area (a practice deemed illegal by the Israeli government). Curated by Jonathan Turner, and put together with the organisation Artists + Allies x Hebron working with Emily Jacir’s Bethlehem project space Dar Jacir, jugs of oil and wine from the South Bank sit on one table, while on another balls of dough are left out, with instuctions for a ‘kneading ritual’ as part of Shayma Hamad’s project The Distance of Death from my Hands to my Mouth (2023). Duncan Campbell’s short film Nothing Impossible (2018), captures the restoration and repair of a 1987 Peugeot car, as a community performance of sorts that took place during Campbell’s residency at Dar Jacir; while on a wall nearby hang small sachets of seeds from Vivien Sansour’s seed library. The documents here hold onto a present, but within them is also the potential for transformation and renewal. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Bangkok Art Biennale: Nurture Gaia

Various venues, through 25 February 2025

According to Greek mythology, the first being to emerge from the primordial goop of Chaos (the first entity, often characterised as the Great Abyss) was Gaia, the matriarch of all existing things and the personification of Earth. It seems to be a popular thing now (in the sense that it has reached mainstream art) to invoke the mythical and magical as a means of connecting and engaging with a contemporary global state of polycrises – of which war, climate change, pandemics and the continuous destruction of our world number a few. Nurture Gaia is the somewhat nebulous title and theme of this edition of Bangkok Art Biennale – an exhibition presenting works by 76 international artists. Three things not to miss: Aki Inomata’s video Think Evolution #1: Kiku-ishi (Ammonite) (2016–17), for which the artist’s research into ammonites led to the ‘recreation’ of these prehistoric creatures by introducing a 3D-printed shell to an octopus, and which is more generally a ‘thought experiment’ on how collaborating with nonhuman entities might lead to a reshaping and rethinking of our relationship with the natural world; Tongan-Gadigal artist Latai Taumoepeau’s The Last Resort (2020) draws on faiva, a body-centred performance practice, that sees the artist and collaborators wearing brick sandals and smashing glass bottles with ‘ike (traditional Tongan mallets) – the violent action highlighting the destructive impact of climate crisis and ocean pollution in the Pacific; while at Queen Sirikit National Convention Center, Kanya Charoensupkul presents Whitewash for Mother Earth (2024), an epic 14-metre-long mixed-media painting into which sand, water and other natural elements are incorporated, resulting in an abstract work in hues of grey, white, green and faded red, all of which gives it the quality of a slab of bloodstained raw marble. Fi Churchman

Jam Session: The Ishibashi Foundation Collection × Yuko Mohri: On Physis

Artizon Museum, Tokyo, 2 November 2024 – 9 February 2025

How long can a ripe pineapple power a lightbulb for? For Yuko Mohri, who is currently representing Japan at the Venice Biennale, such whimsical questions are there to be answered. In her often-improvised work, created in-situ and using everyday objects found and purchased in the local neighbourhood, she seeks to bring into focus the otherwise invisible forces that shape our world, from rainfall to magnetic fields, electricity to decomposition. And so pineapples and other fruit, fresh from the market, are connected up to circuit boards and lightbulbs; as they decay, their moisture levels change and the lights flicker on and off. At Artizon Museum in Tokyo, her interest in the gentle chaos of these unpredictable elements is heightened by the pairing with works by the likes of Monet, Matisse, Brancusi and Duchamp, chosen by Mohri from the archive of the museum’s Ishibashi Foundation Collection in the latest of their annual ‘Jam Session’ collaborations with contemporary artists. A combination of restaged works by the artist and new pieces created in response to the collection, she introduces instability and experimentation into the orbit of an otherwise static art-historical canon. Mohri’s kinetic works are best characterised by the noises they produce, from the drip-drip of leaking water to the clanking of metal against metal, or the notes of a solitary piano. In On Physis, these combine in a fuzzy, ambient wash of sound and motion, as rich with surprises as people-watching on a crowded street. Louise Benson