ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2015 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the lead-up to the Venice Biennale opening.

Vincent Meessen is representing Belgium – together with guest artists Mathieu K. Abonnenc, Sammy Baloji, James Beckett, Elisabetta Benassi, Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, Tamar Guimarães and Kasper Akhøj, Maryam Jafri, Adam Pendleton. The pavilion is in the Giardini.

What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

The Belgian Pavilion will host an international group exhibition titled Personne et les autres: Vincent Meessen and guests. In an attempt to break the traditional format of Belgium’s representation in Venice to date – which has mostly featured solo or duo exhibitions by Belgian artists – my project Personne et les autres challenges the notion of national representation by opening up the Pavilion to include multiple viewpoints. I developed the exhibition concept in close collaboration with curator Katerina Gregos and we invited ten other artists from four continents, all of whose work has explored the question of colonial modernity. For the first time, the Belgian Pavilion also features artists from Africa. Personne et les autres explores the consequences of political, historical, cultural and artistic interactions between Europe and Africa during the time of colonial modernity, and after. Probing unknown or overlooked micro-histories, the exhibition reveals alternative forms of modernity generated by colonial encounters and the aftermath of African independence.

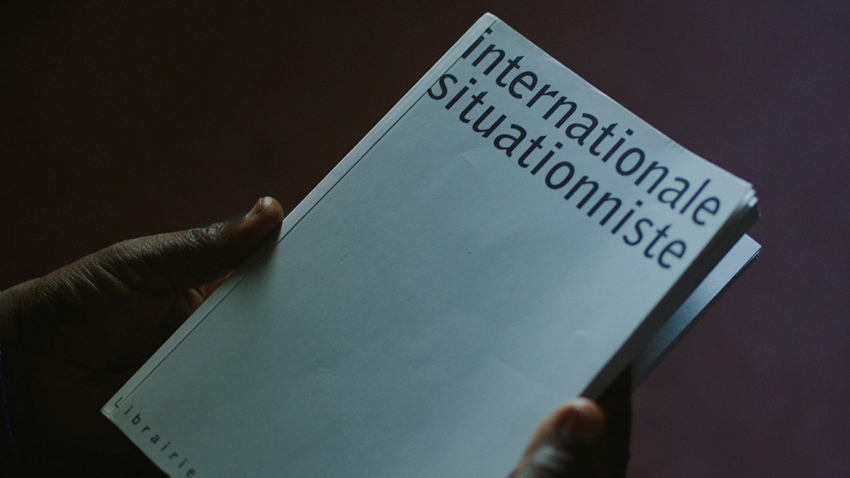

The work circumvents the trap of Situationist mythology, in which Guy Debord has been consecrated as the hero and epicentre of a revolution, and reveals the little known participation of African members in the Situationist International

For the show I have produced a three-channel video installation set in an immersive sculptural setting. Entitled One.Two.Three, the work revisits the role of largely unknown Congolese intellectuals within the Situationist International. Pierre-Olivier Rollin, the director of BPS22 – the museum and contemporary art centre in Charleroi – unexpectedly alerted me to the existence of an unpublished document: the lyrics of a protest song, signed by a former Situationist, Joseph M’Belolo Ya M’Piku, written in Kikongo in May 1968. The document revealed a totally unknown episode of the Situationist Internationals history, so I worked with Joseph [the writer] to re-interpret the text in the form of a musical work. For this I collaborated with a group of female Congolese musicians and the Grammy award-winning musical producer Vincent Kenis (producer of Congotronics), and filmed their version of the song in Kinshasa in the nightclub Un Deux Trois, established in 1974 by the legendary Congolese musician Franco Luambo (1938 –1989), bandleader of the famous rumba orchestra OK Jazz. One.Two.Three circumvents the trap of Situationist mythology, in which Guy Debord has been consecrated as the hero and epicentre of a revolution, and reveals the little known participation of African members in the Situationist International, the last of the international avant-garde social movements.

Are you approaching this show in a different way as to how you would a ‘normal’ exhibition?

I am really interested in the idea of ‘collective intelligence’, as I call it. Choosing not to have a solo exhibition in the Belgian Pavilion might seem rather unconventional, but in fact a large part of my practice is based on collaboration. Also in my ‘para-curatorial’ activities, I often invite artists with similar concerns to collaborate on projects. So my exhibition project for the Belgian Pavilion is very much in line with my practice to date, which has always involved a dialogue with others and the creation of a shared space of artistic exchange.

What does it mean to ‘represent’ your country? Do you find it an honour or problematic?

The Belgian Pavilion as I conceive it, is not a space of national nor communitarian representation. It restages a kind of internationalism that has structured the last century, and that is said to be swept away in 1989. Officially, I represent only one part of the country (the French-speaking part that is now called the Federation Wallonia-Brussels), as the two main linguistic communities of Belgium alternately ‘inherit’ the Pavillion. The funny thing is that my work is actually better known in the (Dutch-speaking) north of the country. But my proposal for the Belgian Pavilion – that opens it up to artists from other countries and continents – is precisely seeking to get out of this communitarian logic, and clearly rejects the deadly tendency to identify only with one’s ‘own’ community. We are all the ‘other’ to someone. Difference is the basis of all creation.

How are you approaching the different audiences who come to Venice – the masses of artist peers, gallerists, curators and critics concentrated around the opening and the general public who come through over the following months?

Although the exhibition is very much anchored in the past, it re-considers history with a view to making a link with present-day issues through visual art. Both myself and the artists in the exhibition share a concern for history: in particular the rewriting and re-contextualising of deliberately marginalised histories. We bring them into the present to be viewed alongside contemporary concerns, offering an alternative understanding into how the past can impact the present.

Also, it is an exhibition of a very visual nature, with some works that are very impressive by form, so I believe the exhibition will already intrigue the visitor at first sight to dig deeper into some of the more complex historical, political and social issues that are being explored within it. Mediation is also very important in this case, especially with so many visitors coming to the Biennial who are not necessarily contemporary art specialists. So we are producing an exhibition booklet which will be freely distributed, that elucidates the concept of the show and the key ideas behind the artists’ works.

What are your earliest or best memories of the biennale?

I haven’t been a regular visitor of the Venice Biennale, but I have some good memories of Ed Ruscha and Stan Douglas from 10 years ago. Sometimes artworks can inhabit you for a long time.

You’ll no doubt be very busy, but what else are you looking forward to seeing?

Joan Jonas, who is going to bewitch the American Pavilion. Also, prehaps more unexpectedly, I am looking forward to exploring the Armenian Pavilion and I hope it will provide an occasion for Armenian artists of the diaspora to enrich the discourse and to offer perspectives other than the single one of the memory of the genocide – which is of course a crucial issue, but it sometimes weighs too heavily on the back of the artists.

How does a having a pavilion in Venice affect the art scene in your home country?

That is a difficult question to answer as Belgium is already present at the Venice Biennale since 1907. In fact, the Belgian Pavilion itself was the first foreign pavilion to be built in the Giardini, during the reign of King Leopold II (a prominent figure in the colonial interaction between Belgium and the Congo). Nowadays, the investment from the Federation Wallonia-Brussels in the Biennale is relatively big in contrast to the rather limited financial support for the visual art scene at home. So art professionals expect a lot from it, and righteously so. We hope that the tremendous work done by the artists, the curator and the team will live up to these expectations.

Read all responses to the Venice Questionnaire 2015 edition published so far

Read all 30 responses to the Venice Questionnaire 2013 edition

Online exclusive published on 6 May 2015.