ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2015 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the lead-up to the Venice Biennale opening.

Camille Norment is representing the Nordic pavilion. The pavilion is in the Giardini.

What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

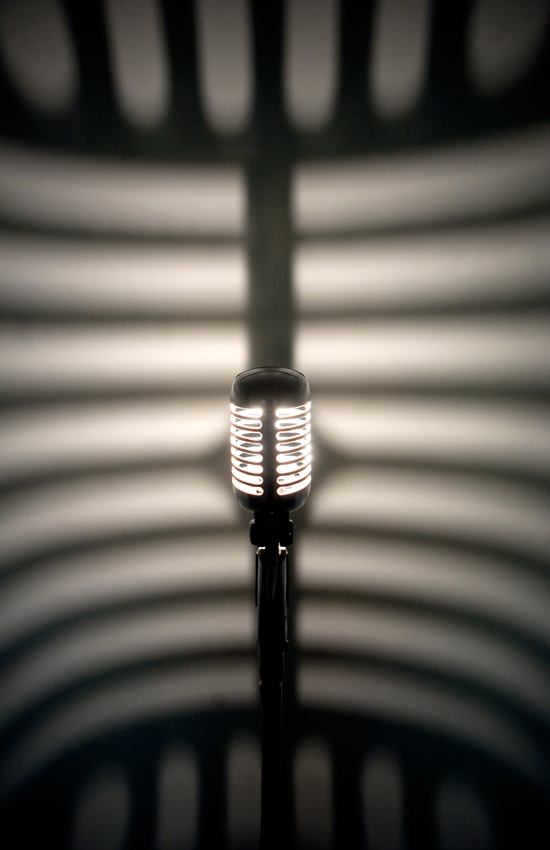

In Rapture in the Nordic Pavilion, I will create a multisensory sonic and sculptural space traversed by a strong dynamic force such as the wind, intense sound, or a historical moment so that after leaving the pavilion there appears to be a state of excitation and an ongoing, unfinished moment – a situation hovering between poetry and catastrophe. Within the pavilion visitors will hear a new composition of a chorus, and the sounds of the Glass Armonica which will emanate from the glass membrane of the pavilion. Sculptural elements based on projectile boom microphones, and shattered glass (reflecting the windows whose panes have been ‘over-excited’) reinforce the sonic experience.

Are you approaching this show in a different way as to how you would a ‘normal’ exhibition?

The architectural structure of the Nordic pavilion is one that unites the outside with the inside and is open to the elements in a way that is elegant, but very challenging as a contemporary exhibition space. As an historic artifact, the pavilion itself is an ‘untouchable object.’ Practically and conceptually, I treated the pavilion as a space that must contend with external forces, such as nature, weather etc. There is also an interesting resonance that the notion of ‘inside/outside’ has with some of the social challenges occurring in the Nordic region and across all of Europe today. As such, it is a site-specific installation. Approaching a site in consideration of its specificity is something I’d certainly consider normal for my way of thinking.

What does it mean to ‘represent’ your country? Do you find it an honour or problematic?

Of course, it’s an absolute honour to participate in the Biennale, and certainly to exhibit in the Nordic pavilion. But I can’t really say what ‘representing’ a country is supposed to mean. A lot of discourses in recent years, certainly within the context of the Venice Biennial pavilions, have sought to deconstruct the very notion of representation. It’s not so much about a person representing a country as it is about a particularly relevant art practice, perspective, and conceptual focus that can be offered as a new platform for perception, thought, and discussion. There are many precedents in the biennial, so I find it more interesting to keep pushing the dialogue beyond and forward.

How are you approaching the different audiences who come to Venice – the masses of artist peers, gallerists, curators and critics concentrated around the opening, and the general public who come through over the following months?

I hope I am treating the audiences as I might always do. My work is built upon layers of perception, beginning with immediate sensual and sonic experience, which is available to everyone. There is a lot of other information that can augment the experience if one is interested in delving deeper. However, I want to make the installation, performance series, and publication accessible and substantial on many levels, while offering space for varied individual interpretations.

What are your earliest or best memories of the Biennale?

Absolutely 1993 – my virgin year at the Biennale. Before then, I was largely attracted to expressionist modes in Modernism and hadn’t yet fully understood, much less fully articulated a voice among contemporary modes of art practice. It was like a being kid in a toy store from the future. I was most impressed by the Arsenale, and always look forward to experiencing how the Biennale themes unfold through the exhibitions. One of my favorite works from all of my Biennale visits was Hans Haacke’s installation in the 1993 German pavilion. I was particularly struck by the sound created by walking over the broken floor. Personally, to some extent, I’ve returned to re-adopt some of the earlier poetic or expressionist executions I had previous to that time, but more consciously combined with a discourse of the subjective body related to that time. I feel it’s timely and makes sense; the times have cycled back to similarly relevant issues.

You’ll no doubt be very busy, but what else are you looking forward to seeing?

I really want to carve time to run along the beach on the Lido. More so, I hope that I can find a feasible enough route to have a run on the way to the pavilion in the mornings. I lived in Dorsodoro as a student, so the San Marco crowds, and biennial force was something in the distance – I had to travel to get to it. I hope to find that quiet space again and be able to experience Venice with a distance and closeness that I haven’t before. There are also particular historical aspects of the city I want to understand better, such as the history of the glassworks, trade, and the now fetishized presence of the Moors. Perhaps this will be another start.

How does a having a pavilion in Venice affect the art scene in your home country?

Art seeks to operate beyond frameworks defined by political structures so it’s no surprise that I’ve only been congratulated and offered a lot of support. Many have found it curious that I should be exhibiting in the Nordic pavilion (given that I am American-born), but just as immediate is the thought that this should be irrelevant. We’re all quite used to, and rarely question the fact that national sports teams are typically comprised of players from all over the world, I was recently told. It’s interesting because, of course, it is still very relevant today, especially given such a strong return to nationalist ideals of recent years. I feel my participation represents the desire for a positive moving force.

Read all responses to the Venice Questionnaire 2015 edition published so far

Read all 30 responses to the Venice Questionnaire 2013 edition

Online exclusive published on 9 May 2015.