ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists and curators exhibiting in and curating the various national pavilions of the 2017 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the lead-up to the Venice Biennale opening (13 May – 26 November).

The NSK State Pavilion takes its cue from NSK State-in-Time, founded by artist collective Neue Slovenische Kunst (NSK) in 1992, which was a utopian formation without physical territory or national affiliation. The pavilion seeks to questions ideas of the state, citizenship and identity through collaborations with migrant communities and stateless individuals. Turkish artist Ahmet Öğüt has been selected to shape this first iteration of the Pavilion. You can find it in Palazzo Ca’ Tron, Santa Croce 1957, IUAV University.

What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

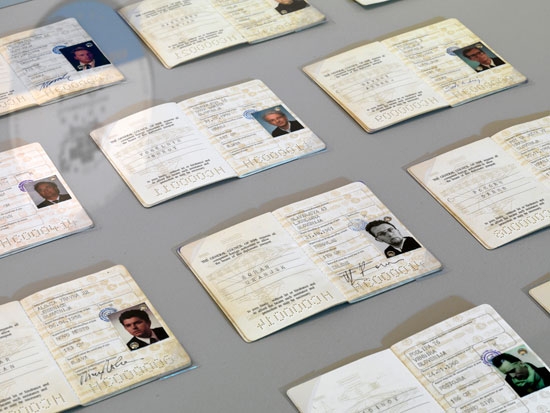

In early 1992, shortly after the collapse of Socialism and the tumultuous break-up of Yugoslavia, the NSK State-in-Time (Neue Slowenische Kunst) emerged at a moment when a radical rethinking of the nation state was necessary. Since then NSK State-in-Time has not manifested itself geopolitically, but has instead become a unique state that has an open form of citizenship in contrasts with spatial states. This, the first NSK State Pavilion, is commissioned by IRWIN, curated by Zdenka Badovinac and Charles Esche, and directed by Mara Ambrožič. I was invited to design the Pavilion. I took this challenging task and created a new set of installations that will give a physical experience of gravity. The Pavilion will be governed in collaboration with Humanitarian Protection Applicants, Sans Papiers, and stateless individuals. The space will be experienced in different parts: “An Apology for Modernity”, a room including over 100 responses from contributors, and a NSK Passport Office. There will also be an inaugural lecture by Slavoj Žižek.

How is making a show for the Venice Biennale different to preparing a ‘normal’ exhibition? Or another biennial?

In 1987 Venice and its lagoon were added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. This alone makes it a very unusual place to work. Often arranging things that would elsewhere be simple can become very complicated in Venice. At first everything seems impossible because of regulations, but with enough creative thinking many things are possible.

There are a huge number of biennial exhibitions across the world nowadays. Do you think the Venice Biennale still has a special status, and why?

I think the time of specific biennials being ‘must see’ brands is over. Each edition of a biennial must reinvent itself not only in respect to its own heritage, but also as a challenge to itself in order to continue to have a lasting effect on civil society.

What does it mean to ‘represent’ one’s country? Do you find it problematic?

We are no longer in 1910s when the notion of nation state pavilions made sense at a major world fair. That notion must be playfully challenged and redefined. I find it more interesting when an artist represents another country’s pavilion.

The Venice audience is a diverse group. Who is most important to you? The artists, the gallerists, curators and critics concentrated around the opening, or the general public which visits in the months that follow?

In the last year I have visited Venice several times and have had chance to experience a very different kind of Venice. A kind of Venice that most art audiences and art professionals don’t know. A kind of Venice that regular tourists don’t ever experience. For me, the most important thing is that while being connected with the art audience, we give priority to finding sincere ways to connect with the people who actually live in and around Venice.

What’s your earliest or best memory from Venice?

Climbing on top of off-duty vaporettos at 2am in August. Also traghetto rides for hidden shortcuts.

How do you think having a pavilion in Venice can make a difference for the migrant communities, humanitarian protection applicants and stateless individuals it seeks to represent?

A durational pavilion cannot make a difference alone. But NSK State-in-Time is a long-term initiative that has been existing over decades. The NSK State Pavilion will be a non-hierarchical zone that is equally governable by its whole community: from marginalised, undocumented, stateless communities to migrants and citizens. And what we learn from this can be carried on collectively through future platforms.

You’ll no doubt be very busy, but what else are you looking forward to seeing?

Beside NSK State Pavilion, I am looking forward to see Cevdet Erek’s new work .IN at the Turkish Pavilion, the result of the collaborative presentation by Erkka Nissinen and Nathaniel Mellors at the Finnish Pavilion, Candice Breitz and Mohau Modisakeng’s works for the South African Pavilion, Katja Novitskova’s installation at the Estonian Pavilion and Wendelien van Oldenborgh’s work for the Dutch Pavilion.

Click here to read all the Venice Questionnaires so far

3 May 2017