ArtReview sent a questionnaire to artists exhibiting in the various national pavilions of the 2019 Venice Biennale, the responses to which will be published daily in the lead-up to the Venice Biennale opening on 11 May.

Milovan Farronato is the curator of the Italian Pavilion, which features work by Liliana Moro, Enrico David and the late Chiara Fumai (1978–2017). Here we have combined the answers of Moro, and that of Farronato, who introduces the work of Fumai. The pavilion is in the Giardini.

What can you tell us about your exhibition plans for Venice?

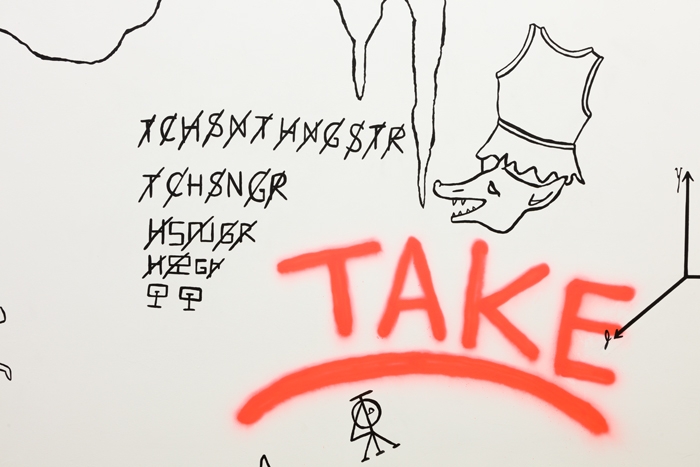

Milano Farronato: Chiara Fumai, born 1978, would have been the youngest of the three artists in the exhibition Neither Nor: The challenge of the Labyrinth and I wished her presentation to focus mainly on one significant new work. Titled This last line cannot be translated, Chiara’s piece will be exhibited publicly for the first time in the Italian Pavilion. It is a large mural which will appear in parts, fragmented and dispersed throughout the labyrinthine display, but also in its full extent within one single room. Chiara had been working on it for one year previous to the last months of her life, originally conceiving it for the exhibition Si Sedes Non Is that I curated at The Breeder, Athens, in 2017. The show was thought as a space for the activation of energies within the visual boundaries of what we had initially intended to be a large mural able to encompass the whole space and embrace elements proposed by other artists too. Chiara was supposed to execute this wall drawing as well as coordinate with me the contributions by the other artists. We immersed ourselves in a draining exploration of a maze of ideas concerning her piece. She developed detailed drawings which were ready to be put into execution in situ: a continuous black line interlacing words in cursive script across the walls, spelling the invocation of the ‘Mass of Chaos’ in the version to be found in Liber Null & Psychonaut (1987) by Peter J. Carroll (a contemporary occultist and a practitioner of chaos magic). The perimeter of this invocation forms a cave, within which a series of symbols and sigils from different magical traditions are enclosed. However, we eventually decided together that it was not the right time to show this work. Its genesis was proving quite draining for Chiara and so we temporarily put it aside. I knew there would be another opportunity to exhibit it in the future.

Liliana Moro: Within the exhibition project/itinerary I will present a wide selection of my works. Amongst this selection there are less known artworks, some of them date back to my early years of production, as well as two new pieces: one, I reckon, represents precisely the way I work and the other is thought specifically for this Biennale. One could say that I traced my own path into the exhibition itinerary; the road intertwines with those created by the other two artists of the Italian Pavilion and it also illustrates what I do, what I think and my constant predisposition to research.

What does it mean to ‘represent’ your country? Do you find it an honour or is it problematic?

LM: I do not think that the term problematic is appropriate; I think that Italy finds itself in a complicated and delicate time, in which some political and cultural choices cannot be agreed with. It is not simple to feel at ease in this context, especially those people, like me, who are aware of and participate in the political and cultural progress of their own country. Nonetheless I am absolutely honoured of the curator’s acknowledgement and to represent a relevant portion of the Italian cultural and artistic panorama of the last 30 years.

Is your work transnational or rooted in the local?

LM: Due to its essence, art breaks out from borders and boundaries, it is extra-territorial, transnational. I could say that I am an international artist, who loves her territory and roots deeply.

MF: In her practice, Chiara was fundamentally interested in myriads of sources which she quoted, enacted loudly and softly, or even simply intertwined with something else. The title of the 2016 edition of the Volcano Extravaganza festival I curated in Stromboli with Camille Henrot was I Will Go Where I Don’t Belong – I believe that Chiara is one of those artists who embodies this approach. She used to explore territories that were not hers. Her performances were crossroads of different cultural and philosophical references, with a marked European/Mitteleuropean matrix.

Whilst being transnational in its full breadth, her work dialogues with the legacy of specific female characters that she used to call her ‘wretched’ and ‘noblewomen’, primarily of Italian origin. She used to quote them, give them voice by performing their history and experiences. Her research also looked at other seminal figures and genres within Italian culture. I often imagined to exhibit some of her works alongside Ketty La Rocca’s, for instance. One of Chiara’s early references was Italo Disco, which also became the theme of her last exhibition at Guido Costa Projects in Turin in 2018.

With specific regard to the work for the Italian Pavilion, I would say This last line cannot be translated is transnational by its very nature: it was conceived by Chiara, an Italian artist, through conversations with me, based in London, for an exhibition taking place in Athens, while she was in residency at ISCP (International Studio & Curatorial Program) in New York. Furthermore, we were in dialogue with many international artists inviting them to present their work within Chiara’s immersive mural, their presentations reflecting the spirit of many other cultures, in particular Western and Eastern spirituality and philosophies.

How does having a pavilion in Venice make a difference to the art scene in your home country?

LM: Italy has art in its DNA. It would be enough to say this to understand how valuable it is to have an Italian Pavilion at the Biennale di Venezia which, let’s not forget, was born in 1893 to promote the new Italian and foreign artistic tendencies. From 1999 to 2005 there was not an Italian Pavillion and I believe this was a huge fault that prevented many from acknowledging new researches and studies.

MF: The Italian Pavilion as we have it today is a fairly recent achievement. The first exhibition that was ever presented in it was the one by Giuseppe Penone and Francesco Vezzoli curated by Ida Gianelli in 2007, before then, for many years, Italy just hosted the international exhibition. It feels good to have a pavilion!

If you’ve been to the biennale before, what’s your earliest or best memory from Venice?

LM: I participated at the Biennale in 1993 curated by Achille Bonito Oliva. I know Venice very well, I also taught three years at IUAV University. It is a one-of-a-kind city, just extraordinary, and I love to go back there.

You’ll no doubt be very busy, but what else are you looking forward to seeing?

LM: For a starter, I would like to visit the whole Biennale! It takes time and attention. There are many exhibitions opening during those days in various locations throughout the city, if I do not manage to visit them all I will come back to Venice.

The Venice Biennale runs 11 May – 24 November 2019