The 58th edition, Is it morning for you yet?, attempts to substitute the internationalism of the art market for cross-cultural solidarity

An exhibition is a living body, a curator once told me. If that’s true, biennials have lately needed some resuscitation. In response to this year’s Documenta, The New York Times declared, ‘The dream of a global art world has died’. I’m not so sure, but I’ve lost track of all the glorified group shows that have buried market trends beneath woke discourse and inscrutable poetics. To cast the latest edition of the quinquennial Carnegie International with the lot would be to ignore the earnest success of curator Sohrab Mohebbi’s endeavour. This capacious and heavily researched exhibition features 142 artists and collectives from 40 territories. Many of them are little known in the US, putting Carnegie’s internationalism to the test.

Anchoring the show is a series of historical capsule exhibitions featuring works from parts of the world that have been subject to US imperialism (an almost impossibly broad category). In ‘Refractions’, one moving presentation – mostly focused on US intervention in Latin American from the 1960s to the 1980s – includes photographs by Susan Meiselas documenting the struggles of the Sandinista revolutionaries in Nicaragua’s bloody civil war; Isabel De Obaldía’s watercolours of gruesome atrocities committed by Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega; and posters designed by Claes Oldenburg and Thuraya Al-Baqsami to protest US support of totalitarianism in the region. Several works reflect on the legacies of the Vietnam War, most powerfully Võ An Khánh’s ethereal photographs of Viet Cong soldiers training and tending their wounded in jungle camps. In this tensely agitprop atmosphere, a rarely exhibited work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres stands out for its quietude: Forbidden Colors (1988), comprising four monochrome canvases painted green, red, black and white, respectively – a combination, the artist notes in a wall label, then forbidden in the State of Israel for its association with the Palestinian flag. Alongside ‘Refractions’, loans from the Museum of Solidarity Salvador Allende in Santiago de Chile, founded during Allende’s presidential-election campaign and continued in exile after his 1973 assassination, include works in support of the Chilean resistance from as far afield as Mongolia.

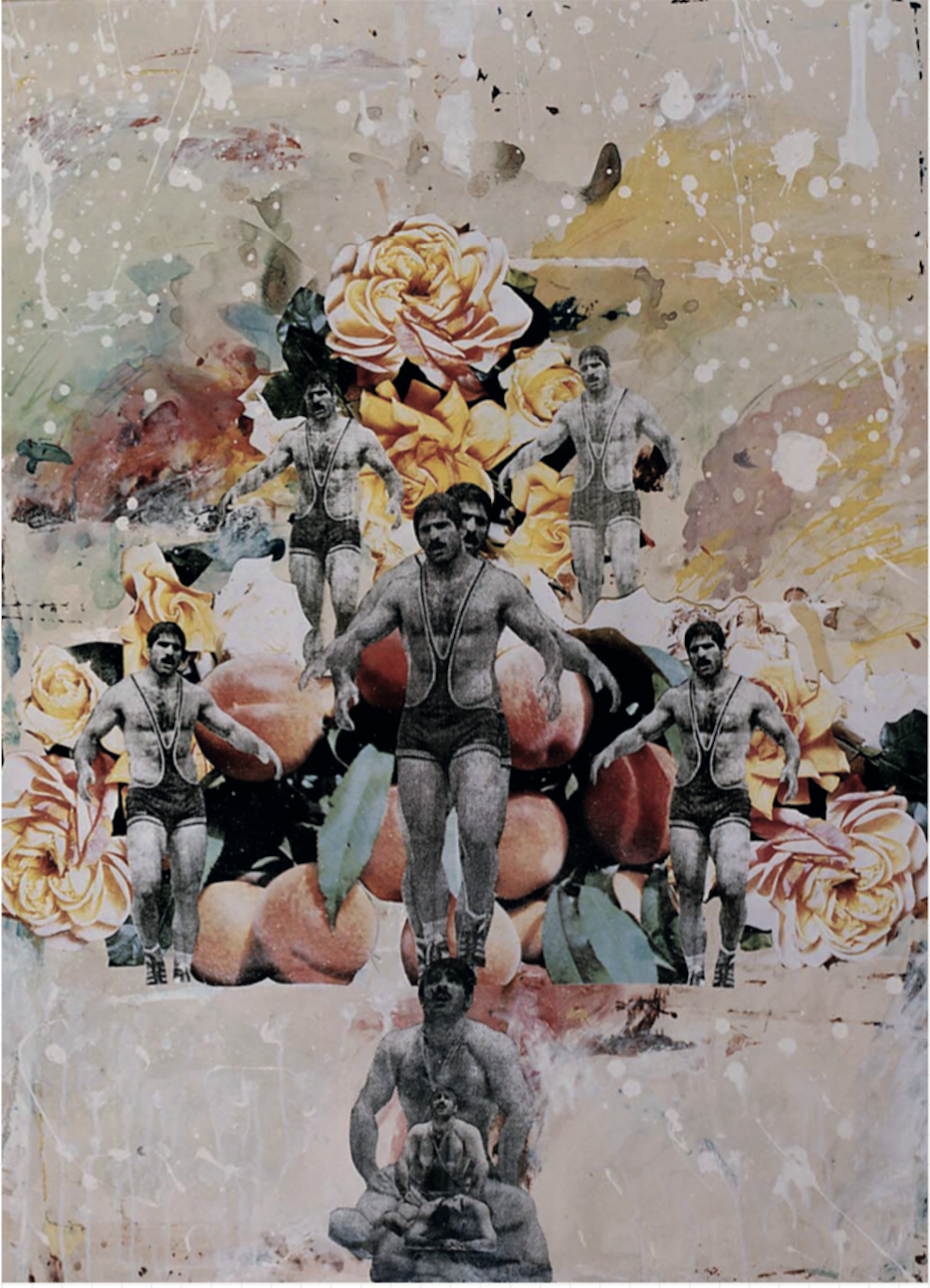

More astonishing still is a dense salon hang collected over several decades by Iranian artist Fereydoun Ave, who ran a gallery in a disused Tehran garden shed until 2009. Many of the works – including homoerotic, painted-on photographs of wrestlers by Ave himself and intricate, surrealist coloured-pencil drawings by Reza Shafahi – are unabashedly feminist and queer. Although Ave is now based between Paris and Dubai, it feels like a minor miracle to see these works in Pittsburgh, especially as protesters fill the streets of the Islamic Republic demanding an end to the ayatollah’s regime.

Counterposed to these historical works is a newly commissioned presentation by younger artists, many from the Asia Pacific region. Of note are dreamy erotic paintings by Balinese artist I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, recalling the canvases of Christina Ramberg. Tith Kanitha’s sculptures, made from coiled and cut wire, resemble those of Ruth Asawa, but with an unsettling frailty, as though at any moment they might unspool. A ‘temporary garden’ by Truong Công Tùng, comprising chains of hanging gourds threaded with plastic tubing, a monumental curtain made of cacao beads and gorgeous wooden panels in which plants and animals recede into layers of darkening lacquer, invoke the industrialised farmland near the artist’s home in Ho Chi Minh City.

You won’t find many Instagrammable moments here, with one exception: towering gold balloon sculptures by Banu Cennetog ̆lu that fill the Carnegie’s grandiose neoclassical atrium. Each bunch of letter balloons spells out an article from the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but impossible to assemble here. They’ll slowly deflate during the exhibition, a devastating commentary on the erosion of democracy around the globe. Around the perimeter, haunting photographs by Hiromi Tsuchida of objects left behind by victims of the US bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki make their neighbours resemble gilded mushroom clouds.

The pairing reminded me of Alain Resnais’s film Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), a classic meditation on the ways language often fails us when we’re faced with love or loss. At its best, this Carnegie International tackles tough subjects without didacticism, preferring to show rather than tell. The curatorial statement suggests that the exhibition considers ‘the geopolitical imprint of the US’, though most of the younger artists thankfully seem preoccupied with other subjects. “Like any political structure, art works against it,” Mohebbi noted at the preview, an admission more in spirit with the exhibition. Art, here, works against pat chronologies and regional divisions; it trades the internationalism of the market for cross-cultural solidarity. If this show is a body, it’s very much alive.

58th Carnegie International: Is it morning for you yet? across various venues in Pittsburgh, through 2 April