A Gathering of Tomorrow at Starch, Singapore finds the answer in the now

“I come from a future you probably cannot imagine.” Dressed in a white spacesuit, and with a traditional Nepalese gold nose ornament hanging from her septum, the time traveller is trekking through the pristine mountains and rivers in present-day Indigenous Sherpa Nation and Yakthung Nation in East Nepal. Her voiceover narrates her personal story – she has jumped timelines to look for her missing father here – and gives a brief outline of the society from which she hails. There, Indigenous peoples remain sovereign owners of their native lands, their cultures are preserved and their advanced technology enables intergalactic and time travel. The current world, in which Indigenous peoples are disenfranchised, enrages her. “Even as a kid,” she says, “it didn’t take me long to realise that colonialists, Brahminists and capitalists were complete fuckers. I would have kicked their asses if I was [here], I used to think.” But because of the ‘Thakthakma protocol’ – a noninterventionist directive – she is forbidden. Instead, the fight is still ours.

This is Ningwasum (2021), a feature film by Subash Thebe Limbu. The film, with its earnest and urgent political messaging, has become a classic of Asian Futurism, the wide-ranging movement that explores alternative futures through Asian cultures, histories and experiences. It is one of the works in A Gathering of Tomorrow, a group show of four artists curated by Gillian Daniel and Kristine Tan. They ask: ‘How do we connect the coordinates of our past to orientate ourselves in the present and look towards the future?’

Despite the future-oriented title, the show is mostly rooted in the now. The works here (all but Ningwasum made in 2024) present interpretations of Asian cultural heritage combined with technology to explore non-Western ways of thinking and being, by a tech-savvy generation of Asian artists who are also connected with their local cultures and aesthetic traditions.

Advocating for a peaceful coexistence between Asian traditions and more contemporary, globalised influences is the sound installation Antara Muka, by musicians Syafiq Halid and Rosemainy Buang, who work together as ANTARMUKA. The work comprises a series of Malay and Indonesian musical instruments, including drums and gamelan pieces, which hang from wooden frames in the gallery. Placed on and around these instruments are speaker cones, whose vibrations are used to ‘play’ these instruments. On the floor, another set of speakers play the metred clicks of a Western metronome. Elsewhere, other speakers play tracks composed by the artists on the pentatonic or heptatonic scales found in Malay music, and which have a less rigid rhythm that expands and contracts depending on the performers. The overall effect of the installation is an easy-going drift of beats and melodies that flow in and out of focus. The patchwork quality of the music, in which old and new, East and West, exist in suspension, suggests a syncretic form of creativity that values conversation between different musical forms over resolution.

Meanwhile, Arabelle Zhuang’s Interpolations, a group of installations inspired by her travels to Mount Bromo and the Ijen volcano complex in Indonesia, and the caves of Perak and Sarawak in Malaysia, suggests a loose affinity with the environment and native craftwork, with the use of natural materials and traditional mat-weaving techniques. Jute weavings hang from the ceiling; a heavy pile of brown mat is crumpled up to resemble a mountain, on which images of caves are projected; and spindly twigs and sticks, tied together to make fragile geometric structures, are propped against a wall. The curators write that the work ‘meditate(s) on the possibility of a closer relationship to the natural world based on care and consideration’. Perhaps. But the work’s intentions and efforts are too diffuse, and feel more like a work in progress as the artist continues to digest and process her experiences of these sublime volcanoes and caves.

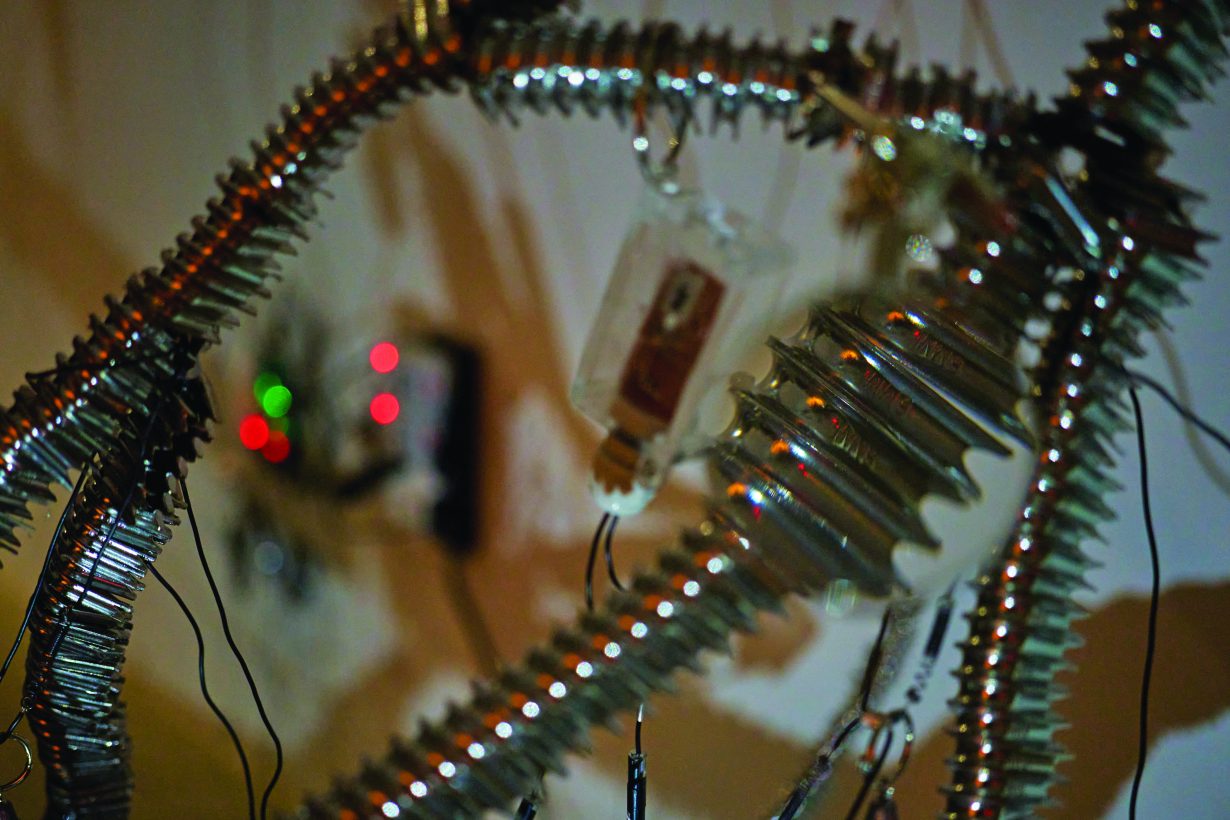

Operating at the more advanced end of the tech scale are Chok Si Xuan’s kinetic assemblages made from machine parts or technical materials. Her works often play in the entanglement between the organic and the artificial, bodies and machines – which speak to a current reality of increasingly bionic bodies with the use of pacemakers, credit card chip implants and so on. Are bodies an extension of technology, or is technology an extension of bodies? For the sculptural installation Prosthesis, Chok dismantled body massagers – very big in the Asian market – tying the motor parts together to make weird machines that jerk and roll against their bindings. They look a little like malfunctioning robotic dogs. Society is awash with anxieties about the ‘rise of the machines’. But these machines, originally made to service the human body, seem themselves broken, their actions compulsive, clacking and clumsy; they are animate but not really intelligent. If this is a vision of the future, it’s a postapocalyptic one in which these servile machines have risen up and eventually gone to seed. But who says ‘Asian futurism’ has to be optimistic?

A Gathering of Tomorrow at Starch, Singapore, 6–28 August