The year in sex: 2024 pushed everyone toward a horizon of further abjection, in which we ventured few dreams for the future, erotic or otherwise

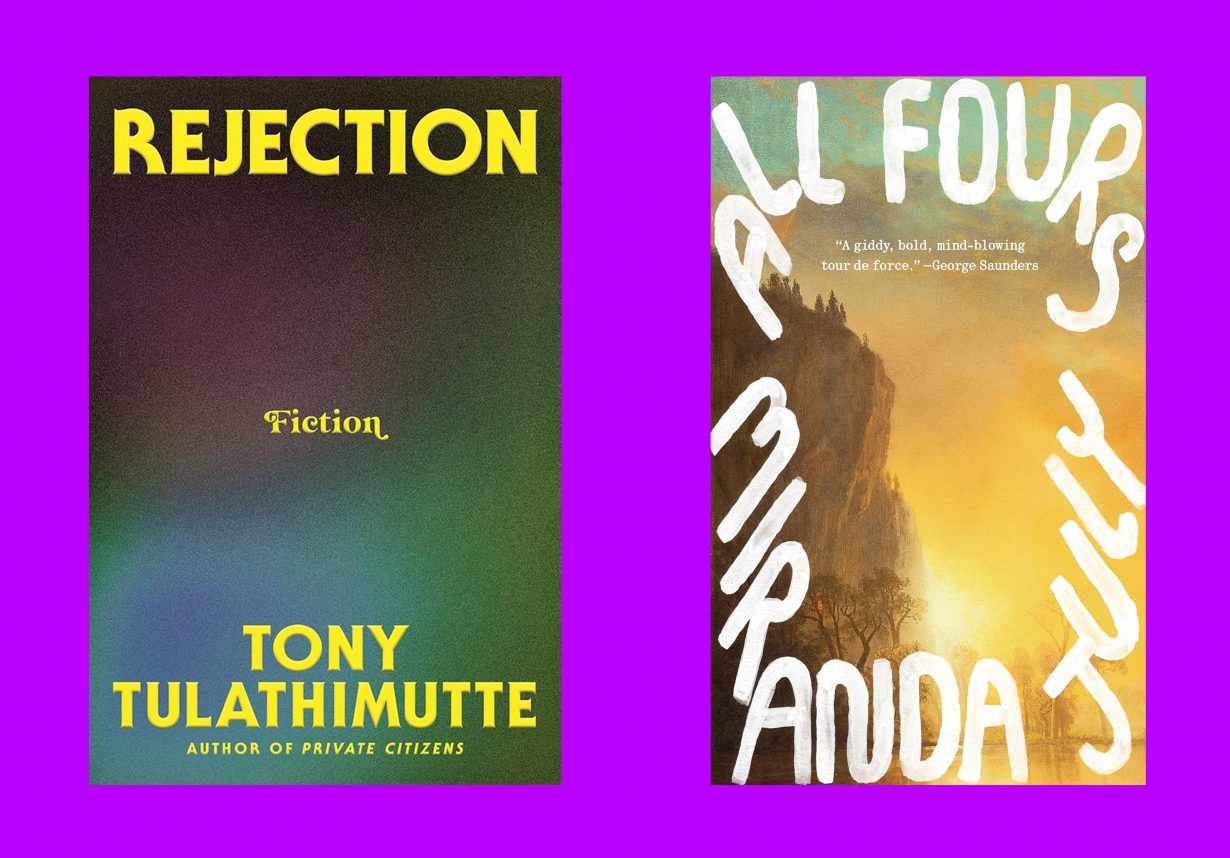

By some measures, this moment marks a golden age for perverts. The internet is replete with OnlyFans accounts, fetish subreddits and amateur erotica. Sex toy innovation has moved beyond the vibrator to devices like the clit-sucking, ballad-inspiring rose toy and the refreshingly low-tech ‘water diverter’. Female TikTok users, including but not limited to so-called BookTok gooners, have meme-ified visceral expressions of desire—a tear just ran down my leg, both my lips smiled, my fingers are tired, and raw, next question—which they deploy profligately, on fan edits of cartoons and pictures of headless mannequins alike. Famously, Gen Z is sick of dating apps but in 2024, hookup options like Grindr and Feeld increased their user base and revenue. At least two of the year’s National Book Award fiction nominees, Miranda July’s All Fours and Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection, the only two I read, contain graphic, unusual sex scenes. Further, according to my own research, today’s boylove manga and manhwa are as absurd, sweet and filthy as they are plentiful.

And yet only someone very insulated or very foolish would suggest that sex escaped the miasma of bitterness and despair that blackened 2024. Mainstream media coverage in the US centred its absence and disavowal, whether actual or threatened, with young women framed as the troublemakers. Well before America’s post-election fascination with South Korea’s 4B movement, there was a sustained swearing off of apps and casual sex due to incessant disrespect and disappointment. On social media, mass bonding over the dismal state of modern romance was and remains ubiquitous: women reported that men choked and slapped them in bed without discussion, let alone consent, running a script they learned from porn, locked into patterns forged in solitude. Even more gentlemanly lovers were prone to replicate today’s version of casual dating: degrading, asymmetrical situationships in which, to paraphrase one woman, you’re his girlfriend but he’s not your boyfriend. (An exemplary communication: 12 hours after he spooned you to sleep and mentioned that his mother would adore you, he texts that he’s not looking for anything serious.) And despite the persistent myth of the voraciously promiscuous man, a lot of them – and this is far too unacknowledged for my taste – don’t want to have sex with anyone but themselves. They’d rather collect beautiful people willing to sleep with them and get off on the denial.

Meanwhile, coupled women’s paranoia runs amok. They post screenshots of text conversations online to ascertain from strangers if their partner is cheating. (The crowd-sourced response is always yes.) They instigate intra-relationship fights about celebrities and Instagram likes, reassure one another that following a hot girl’s account is a type of infidelity. They ‘crash out’ when a TikTok they’ve made to show off how cute their man is gets too many views and the comments are full of – well, we already covered that.

Everyone has an opinion and an explanation for why people, especially the straight ones, are so hopelessly impaired these days when it comes to sex. It’s the pandemic’s aftereffects, or Botox, antidepressants or the erasure of third spaces, the unreasonable expectations set by romance novels or the government. There’s no common ground from which these discussions spring: what sex is, as well as who and what it’s for, are assumptions unexamined, and the obscured perspective changes with every new open mouth. Without foundation, these debates take place in free fall, all parties hectoring into the void. Whether sex is any good or not remains an open question. Even pundits ostensibly in favour of young people doing it more seem compelled by allegiance to heteronormativity and social reproduction than a vision of pleasure and authentic connection. As ever, sex is irresistible, incoherently conceived, dangerous, addicting, morally wrong, criminalised, confusing, unsatisfying, difficult to obtain. And if you’re not having it in a certain way, you’re acting against national interests.

Nothing does more to eradicate sex’s sexiness than its abuse as a tool for social control. Young women’s flirtation with the refusal to date or sleep with men, misguided or unconvincing though it may seem when articulated off the cuff for a 20 second video, is fully intelligible. It is an attempt to erect a wall of ‘no’ while in the US the government dismantles their right of refusal, a bid for protection in a country that’s promised they will have none. For your body to be wielded against you through rape, forced pregnancy, the denial of gender-affirming care (or healthcare of any kind) is not a footnote to one’s behaviours and desires, it is a dye poured in the bath. The tragedy of this trend is not the impulse behind it, but the atomisation of those who need collective, not individual, power, and are bereft of structures that create it—to say nothing of the economic conditions that make child rearing feel like a feasible option. (See Jenny Brown’s 2019 book Birth Strike for additional context.)

We may dwell in a pervert’s paradise, but no one invokes the spectre of sexual revolution or utopia, not anymore. We venture few dreams for the future, erotic or otherwise. Sex always has consequences, some socially designed and some biological, but human intervention can mitigate or outright remove many of them. Instead, through policy and culture, material punishments and psychological warfare, 2024 pushed everyone toward a horizon of further abjection. There will be no forgiveness and no help, suggest politicians of all stripes, not when it comes to sex or anything else—homelessness, hunger, climate crisis. This is evident in American domestic legislation and policing. It’s also seen in the genocides abroad and the relentless propaganda selling them at home.

And yet again I say, and yet. People had sex this year, good sex. Sometimes loving, transformative, nourishing sex. Intimacies are anecdotal and ill-suited for national coverage. I keep thinking of a man on Reddit who confessed his milking kink to his wife, after which they immediately drilled a hole in a table together, set up a camera and filmed ‘one of the hottest nights’ of his life. ‘Take this as your sign to trust your partner,’ he wrote, ‘and if you’re reading this wifey, thank you for loving me so good.’ My sexual utopia would be just a regular utopia; you know the one. Where people are funny and curious and kind and thoughtful, and everyone gets what they need in terms of practical resources and medical support. The perverts do their thing, the abstinent do theirs, and people swap categories at whim. We could have that, I think. Couldn’t we? And yet we are so far away.

Charlotte Shane is a writer based in New York. She is the author of An Honest Woman (2024) and Prostitute Laundry (2015)