A third-generation ‘veteran’ of the Second World War takes on silence, cultural dislocation and Orientalist myth in an increasingly experimental body of filmwork

“War has stayed unimaginably alien to me,” says Sylvia Schedelbauer in her first work, Memories (2004). Yet the role that the Second World War had in shaping the filmmaker’s identity connects the film – and therefore her oeuvre, in which the theme of war figure extensively – to more contemporary narratives of displacement, often themselves a consequence of conflict-ridden countries.

Schedelbauer, born in Tokyo in 1973 to a German father and a Japanese mother, moved to Berlin in her twenties to study at the Berlin University of the Arts and has lived there since. Her films, which have screened at numerous festivals and institutions, were presented in a retrospective at the latest edition of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, held each spring in Germany.

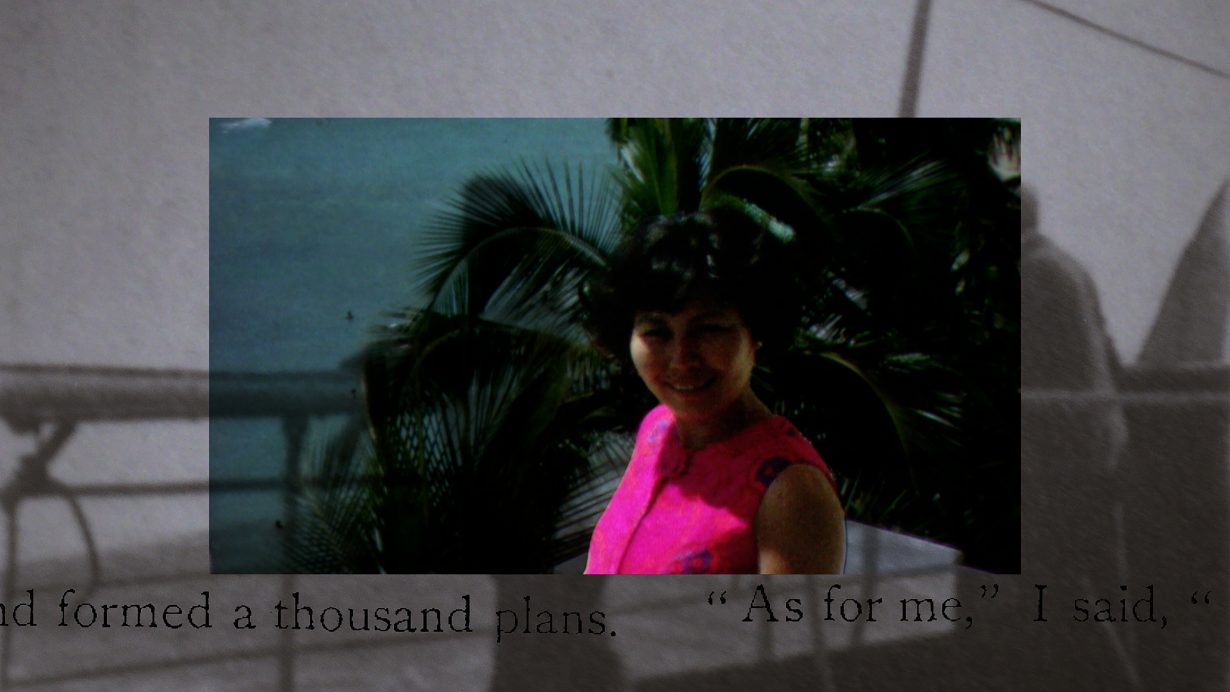

Oberhausen, one of the oldest short-film festivals in the world, kickstarted Schedelbauer’s career with Memories, a profoundly personal short documentary film on the unreliable nature of memory and cultural identification in a transnational context, which was presented at the festival the year it was made. In it, Schedelbauer attempts to (re)construct her family history, using family photos to map out what led to her parents’ meeting in Japan, the details of which were never disclosed to the filmmaker. In a voiceover the filmmaker admits to having based her version of the family’s history (including mentions of her grandfather’s involvement with the Nazis) on fragmented conversations she had with her father. Her mother, on the other hand, had always been reluctant to share details of her past. Intriguingly, although Memories strives to critique the limits and fallibility of human memory, it also demonstrates how much history is susceptible to distortion and subjectivity. Photos of Schedelbauer’s parents are presented in a slideshow, but the filmmaker’s voice is the only one allowed to comment on them. Because of her parents’ silence about their past, Schedelbauer grew up in an identity vacuum, stripped of the cultural coordinates to make sense of her mixed-heritage existence within the fractured geopolitical landscape of the late twentieth century. Memories ultimately reflects on the generational trauma of the children of the Second World War – Schedelbauer’s parents – and the rippling effects it had on the filmmaker and her own generation.

After Memories, Schedelbauer abandoned linearity and narrative in favour of an experimental approach, slowly building a pulsating, cinematic assemblage. In Anna L. Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World (2015), assemblages are described as ‘open-ended gatherings’ that ‘allow us to ask about communal effects without assuming them’ and ‘show us potential histories in the making’. Although inspired by the ecology of mushrooms, Tsing’s assemblages are further qualified as polyphonic, hence shifting the attention to a specific mode of observing their multiplicity, which encourages temporal and spatial simultaneity. Schedelbauer’s films are composed of manifold synergic strata – aural, visual, cognitive – that offer the viewer a heightened experience through the use of the flicker (or strobe effect), found footage and immersive soundscapes. In Schedelbauer’s next film, Remote Intimacy (2007), words and images are no longer in direct relation, meanings are often hidden and the rhetorics of dreams take control. The film relinquishes the confessional commentary of Memories and embraces a multilayered narrative composed of personal experiences, fictionalised writing and literary quotes. Schedelbauer’s early preoccupation with the unreliability of memory here morphs into a grander discourse about cultural dislocation and the impossibility of identifying with a monolithic national historical narrative. Various types of archival documentary footage are used in the film, including home movies, newsreels and educational films, most of which were shot in the United States and Japan. However, locations remain unidentified in the credits, meaning they are recognisable only to those potentially familiar with the trans-Pacific landscape of postwar American–Japanese relations. To all others, these images are abstract and unplaceable, and yet they seem to be drawn from a collective consciousness of shared media, the recollection of which resurges as in a hazy dream. Thanks to this pervasive use of found footage, Remote Intimacy gestures towards a subconscious realm, a primordial soup of intertwined memories and experiential connections that lulls the viewer into an oneiric torpor.

Sounding Glass (2011) is another journey into these liminal, mnemonic spaces, in which Schedelbauer’s use of found footage, and particularly here of 16mm ‘orphan film’ (an umbrella term that emerged during the 1990s among archivists to describe moving-image work abandoned by its owner or copyright holder for lack of commercial potential; the concept was later expanded to refer to films that had suffered neglect), is mirrored in the film’s own significance. A man, described by Schedelbauer as ‘one of the grown-up half-Japanese orphans’, stands in a forest and stares into the lens of the camera, acknowledging and sustaining our gaze, before disjointed images of quotidian life are juxtaposed. The flicker is employed extensively in the work with a hypnagogic effect, while the forest surrounding the man seems to allude not only to a place of personal introspection but also to a spiritual locus, a mycorrhizal network of splintered human interconnections reminiscent of Tsing’s organic assemblages. It’s an environment visited again in Wishing Well (2018), a hallucinogenic collage film that follows a boy as he roams alone in the woods collecting and planting seeds. The images of the boy, which, as Schedelbauer explains in a statement, were taken from an educational short on environmental pollution made during the 1970s and then matted frame-by-frame by the filmmaker, flick through the film, cross-dissolved on luscious pictures of trees and images of celluloid film damaged by water. ‘I didn’t want to make an instantly recognizable environmental film,’ she writes, which is why any concerns about the ecological crisis we’re facing become apparent only when details about the film’s source materials are disclosed. Ultimately, Wishing Well’s reading remains slippery, its visuals transcending clearcut spatial and temporal markers. However, such a thematic porousness complements the film’s visual structure, allowing the human and natural worlds to collide.

In her most recent work, Oh, Butterfly! (2022), Schedelbauer orchestrates a symphonic and multifaceted critique of American imperialism via the Orientalist story of Madama Butterfly (1904), blending in elements of her own family history, which thematically connects the work to Memories. Based on the semi-autobiographical novel by Pierre Loti, Madame Chrysanthème (1887), and the short story ‘Madame Butterfly’ (1898), by John Luther Long, Giacomo Puccini’s opera recounts the tragic story of Cio-Cio-San, a young geisha who marries a US Navy officer and eventually commits suicide after being abandoned by the man. Similarly to her previous works, Oh, Butterfly! combines superimposed images – archive footage of a nineteenth-century steamship, various opera productions and film adaptations of Madama Butterfly, 8mm home movies of Schedelbauer’s family – with text and sound to construct a kinetic palimpsest weighing in on a larger discourse on multiracial love and its historical connotations, often dictated by colonialist power dynamics. Audio clips and scenes from David Cronenberg’s subversive M. Butterfly (1993) tessellate the film and perhaps illuminate a different and quite radical interpretative path, in light of Cronenberg’s upending of common tropes of Western dominance and Asian submission. Eighteen years after the critical commentary of Memories, Schedelbauer rearticulates her personal mythology by releasing problematic markers of national and gender identity to the warm embrace of a communal psyche.