We seem to be living in an era of competitive shamelessness

At one point on the long and successful campaign trail for the New York City mayorship, Zohran Mamdani was asked in an interview with the New York Times if he would arrest Benjamin Netanyahu if the latter came to NYC. There’s a distinction, Mamdani responded, between acting with arbitrary authority and following the verdict of the International Criminal Court (which, in 2024, issued a warrant against Netanyahu for war crimes and crimes against humanity). Mamdani said that in respecting international law and arresting Netanyahu he would be following the wishes of New Yorkers, who feel ‘there is a deep shame, an anger and a horror that we as Americans are complicit’.

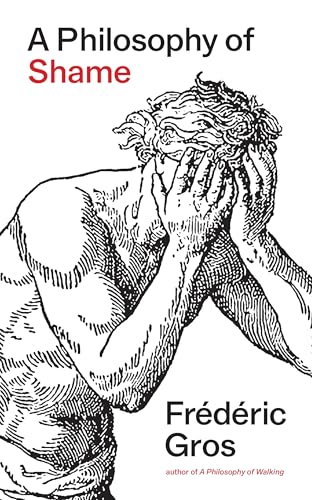

In A Philosophy of Shame, recently translated by Andrew James Bliss, the French philosopher Frédéric Gros notes that the opposite of shame is shamelessness, and that shame, rather than the latter, is a word that carries positive ethical value. In contrast to Mamdani’s evocation of shame as a basis for political action, Donald Trump spoke with characteristic shamelessness in an address to the Knesset after the Gaza ceasefire agreement was announced. He described providing Israel with weapons in response to Netanyahu’s phone calls and demands; his tone was by turns joking, petulant, self-congratulatory, and met with deafening applause. ‘‘Israel became strong, and powerful, which ultimately led to peace,’’ he said.

Gros’s philosophy strives to speak to a broad audience and to accompany, rather than alienate the reader. Alert to how shame quilts together interior psychic experiences (the personal) with a public scene (the social and political), Gros relies upon and fashions psychoanalytic theory into a sprightly vocabulary through which to think of shame as ‘an intimate space whose waters are muddied by the tread of others’. Since there is often no viable distinction to be made between self and other in psychic life, Gros asserts that shame is a reckoning with how ‘the self is encumbered with ghosts and is torn and divided’. Understanding shame requires us to hold the psychic and public dimensions together, Gros posits, avoiding a single definition.

Instead, Gros presents the feeling in its varied contexts – familial, class-based, arising from racism, traumatic as produced by rape and incest. Freed from finding a single account that is adequate to each complex circumstance, Gros can focus instead on how shame is an imbrication of the self with another, or with several others. Class-based shame, for example, involves ‘the internalisation of social contempt’ and by this logic it can also be turned away, by rejecting the system of values that has produced it. The traumatic shame of rape and incest pushes the disavowed shame of the aggressor onto the victim, who takes it into themselves, particularly in situations of incest, where the victim is often in prolonged intimate proximity to the aggressor. The experience of being racialised can produce a kind of shame that is the result of finding oneself internally splintered and constrained by the demeaning attitude of the other, where cruel judgements are taken in as uneasy self-perceptions. It is not so much that each of these instances is a separate or distinct kind of shame, but that paying attention to the conditions in which it is produced allows us to learn something about the many of dimensions of shame.

Shame, Gros suggests, can change. It has an historical dimension. Class-based shame has intensified under neoliberalism, where an emphasis on individual responsibility means systemic inequality is experienced as personal failure. And in the twentieth century, feminist writing and activism have challenged, and to a large degree shifted, perceptions of who is the shameful party in an incident of sexual violence. Gros reads both James Baldwin and Franz Fanon’s writings on shame as ways of exposing, and therefore refuting a racialised imposition of the feeling. In these instances, redirecting shame to its correct location is presented as an important political act. We could event think of it as a form of redistributive justice, with shame as its object.

This redistribution and reassignation of shame clears the ground for Gros’s project of finding an ethical value in the feeling. Drawing on Plato and Confucius, Gros presents shame as a form of restraint and reserve – as something that intervenes preemptively, to stop wrongdoing or injustice. This is not shame as guarantor of social conformity, simply stopping people from what would be frowned upon. Rather, shame functions here as an imaginative link with a future self, and as an appeal to meaningful witnesses to one’s actions – it is a way of cultivating an ‘ethical rapport’ with oneself.

By exposing the limits of one’s knowledge and the arbitrariness of strong beliefs, philosophy can also produce shame. This is not a shame of ignorance, but a shame about acting as though one has superior knowledge or is beyond question. Once again, shame is encountered as a form of restraint and as an opening into the imagination; if I don’t know everything, if I’m not always right, then there is still something for me to learn. It is correct, Gros argues, to feel shame and responsibility at the state of an unequal world, where some profit from the subjugation, both historic and contemporary, of others. Such shame is a form of anger and solidarity, of connectedness and responsibility. It is the impetus to imagine otherwise.

In politics, in displays of wealth, in an encroachment on the rights of women and transpeople, in attitudes towards migrants, we seem to be living in an era of competitive shamelessness. It is as though the appropriation and hoarding of wealth and power is accompanied also by a grandiosity of shamelessness, by a concerted effort to push oppressed people back into positions of humiliation and abjection that inflict undeserved shame. In these circumstances, Gros’s project of recovering shame as a component of ethical living, and indeed as spur for radical action, presents itself as both convincing and urgent. Imagining grounds, other than fear and resentment, on which people can come together and protest, Gros puts forward an unlikely but ultimately convincing alternative: shame. Like Mamdani’s account of the shame of New Yorkers, this also speaks to something quotidian that is not adequately represented in our politics – a sense of ordinary decency, and outrage at brazen injustice. For once, at least for Mamdani, shame won through.

A Philosophy of Shame by Frédéric Gros, translated by Andy Bliss. Verso, 2025.

Read next Is the artworld intelligent?