A group show at Jameel Arts Centre reflects on liminal spaces and in-betweens in a city shaped by migration and displacement

Earlier this year, as part of Hiwa K’s remarkable retrospective at the Jameel Arts Centre, a concrete staircase was installed in the courtyard between the centre and the Palazzo Versace hotel. The stairs led to a small, wall-less room furnished only with a single bed and an antenna. It was devastatingly effective as a twinned invocation of place, namely Kurdish cities under neoliberalism and the increasingly unaffordable bedsits of Dubai. It finds ghostly resonance in Do Ho Suh’s Staircase-V (2008), which occupies a double-height gallery inside the centre. This flight of stairs is a red gossamer recreation of the staircase that connects his New York apartment with his landlord’s. A couple weeks prior, at Neon in Athens, I saw a pink-and-blue recreation of the apartment itself. The multiple cities and shows begin to whirl together like a Mr Krabs meme.

The liminal space, the interstitial, the barzakh. Temporary spaces filled with, in Gulf Return novelist Deepak Unnikrishnan’s phrase, ‘temporary people’. All fitting if somewhat tired metaphors for Dubai, which also serve as the subject of this thoughtful, subtle show, despite its extremely trying description that cites ‘isolation, movement, boundaries, displacement, confinement and waiting’ among several other bromides.

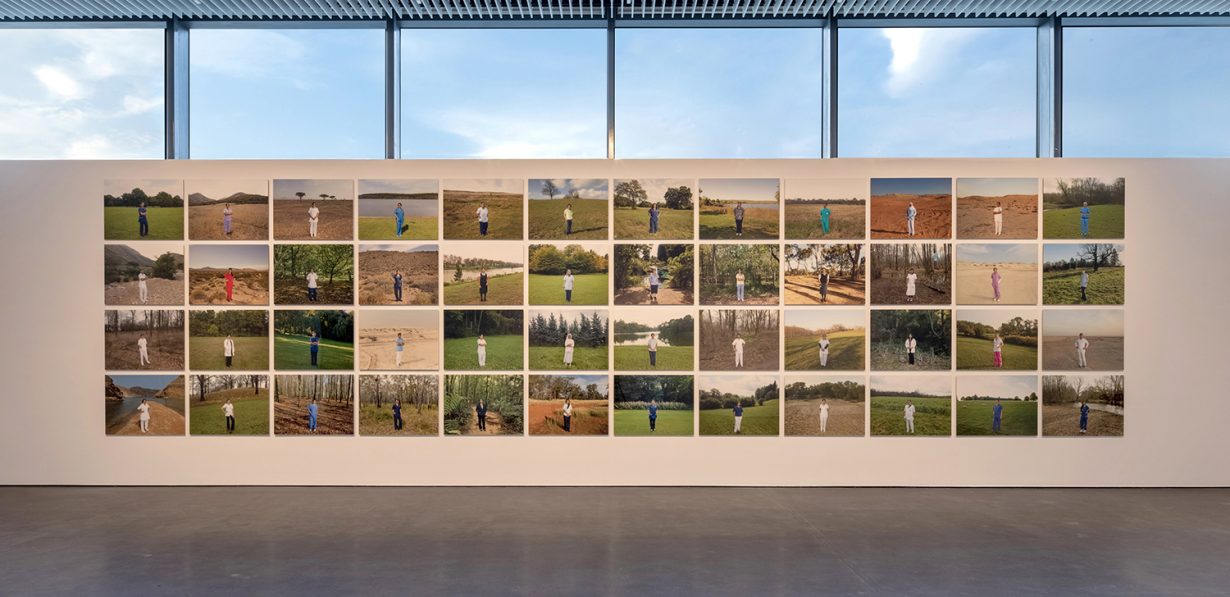

Gulf Return, or the wider feedback-loop of migration from Kerala to the Gulf states and beyond, is writ large in Anup Mathew Thomas’s Nurses (2014), a grid of 48 colour photographs covering one long wall. In each, a woman wearing scrubs poses in an outdoor setting close to the hospitals or care facilities in which they work. We see a variety of landscapes, from sand dunes to the verdant fields and barren wintry forests of more temperate climes, and a range of expressions, too, from stoic to smiling. Nearby, two copies of a small accompanying book provide more information about each person and their migration routes. We learn for example that Shinumol K Pulickal, who is shot hands on hips against a scrubby desert, is currently a cardiac ICU nurse at the Zayed Military Hospital in Abu Dhabi and has previously worked in Bangalore, Kochi, Mumbai and Al-Taif.

Remarkably, the wide, stylised shots and exterior setting mean that these images of dislocation and neoliberal circuits of remittance don’t immediately invoke COVID-19, despite the subject matter. But the pandemic seeps through in the palpable economic anxiety and desperation in Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s A Letter Can Always Reach its Destination (2012). Here, spam emails – fantastical solicitations, pyramid schemes, desultory scams – are performed by amateur actors. They appear as holograms superimposed onto a video in which the other actors line up to await their turn to perform, as if to listen and offer silent support. Even as the work feels a little, well, mean, this backdrop crowd creates a powerful sense of a speaker at a rally or a politician giving a press conference. These are epistolary communiqués from real individuals, yes, but also emissaries of an entire global system of asymmetric access to power, money or simply having your voice heard.

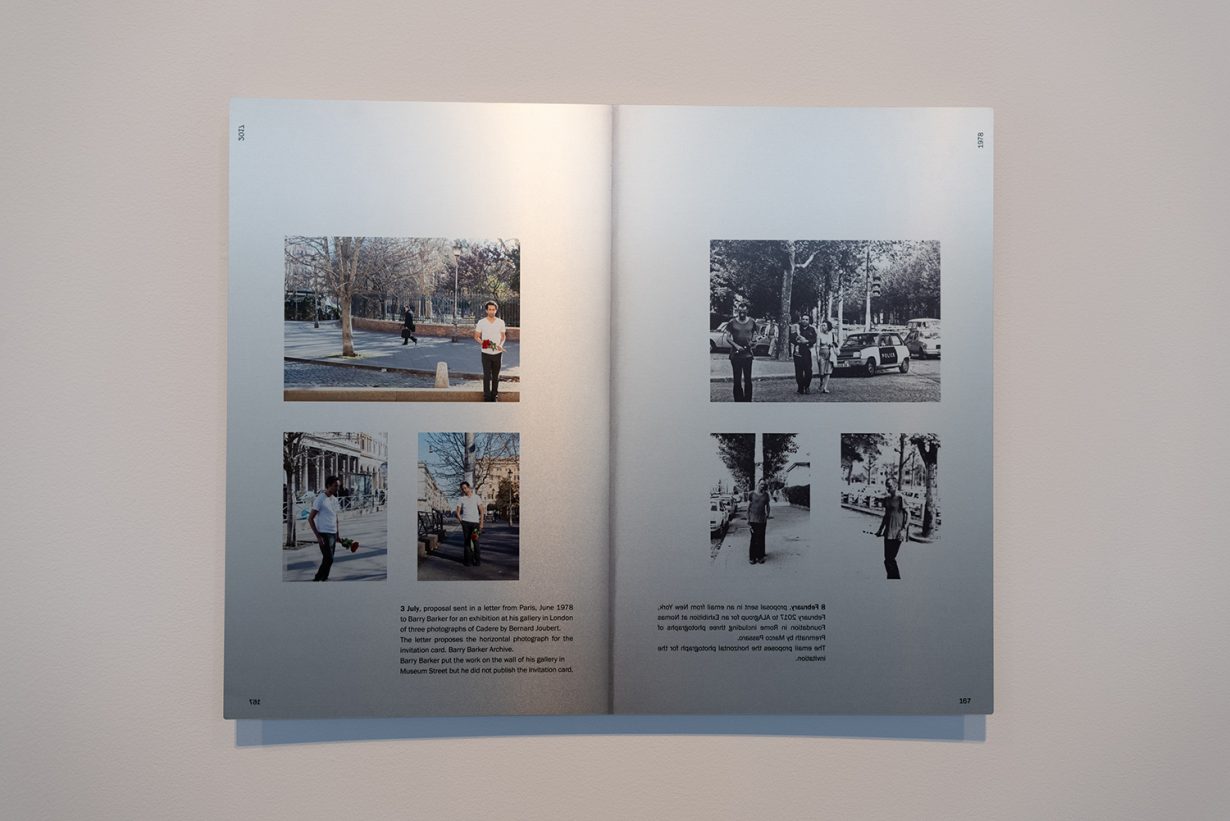

A similar dynamic of entreaties from the Global South to the West – and in turn to the post-West of Dubai – suffuses the show. Among the loveliest works on view come from Sreshta Rit Premnath’s project that links Bangladeshi rose sellers in Rome and Polish conceptualist André Cadere. The latter was best known for his Barres de Bois Rond (1970–78), segmented lengths of doweling that he would surreptitiously lean against the wall at the openings he attended, like immigrants in other people’s exhibitions. In Recto/Verso (2017), images of Cadere holding a striped rod in various city settings are juxtaposed, on the facing page, with images of Premnath, who replaces the rod with a long-stemmed rose: the immigrant artist, then and now. He is further invoked in Premnath’s The Law of Identity series (2017), which collapses the distance between the rose and the rod. Here, painted lengths of wood lean against lined paper featuring short poems: ‘There are two languages one for love another for commerce. Two Euros is a suitable price,’ for example. Later, I realise that its red margins are drawn on and ruled at a leaning diagonal.

Disparate bodies disintegrate into each other in Mona Ayyash’s Folding Bellies (2020), a newly commissioned video in which five participants practise movement exercises. The gestures are small and repetitive, and the video evinces a generative, almost algorithmic accumulation reminiscent of the stock videos filmed for cheap in several more marginalised elsewheres and used as training data for machine vision. But bodies are never so present as in their absence in Hrair Sarkissian’s Background (2013), an elegiac paean to the fading regional tradition of studio portraiture. Posed in front of these backlit images of backdrops, you could be anybody, anywhere: a scuba diver, a piano player, a bibliophile, a patriarch in a single ornate chair. Here, displacement gives way to a familiar feeling of stasis and resignation: of being stuck, making the same old moves in an in-between space.

The Distance from Here, Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, 8 September – 22 January 2022