Though famed for his self-portraits, the artist is also – and perhaps primarily – relating the recent history of his homeland

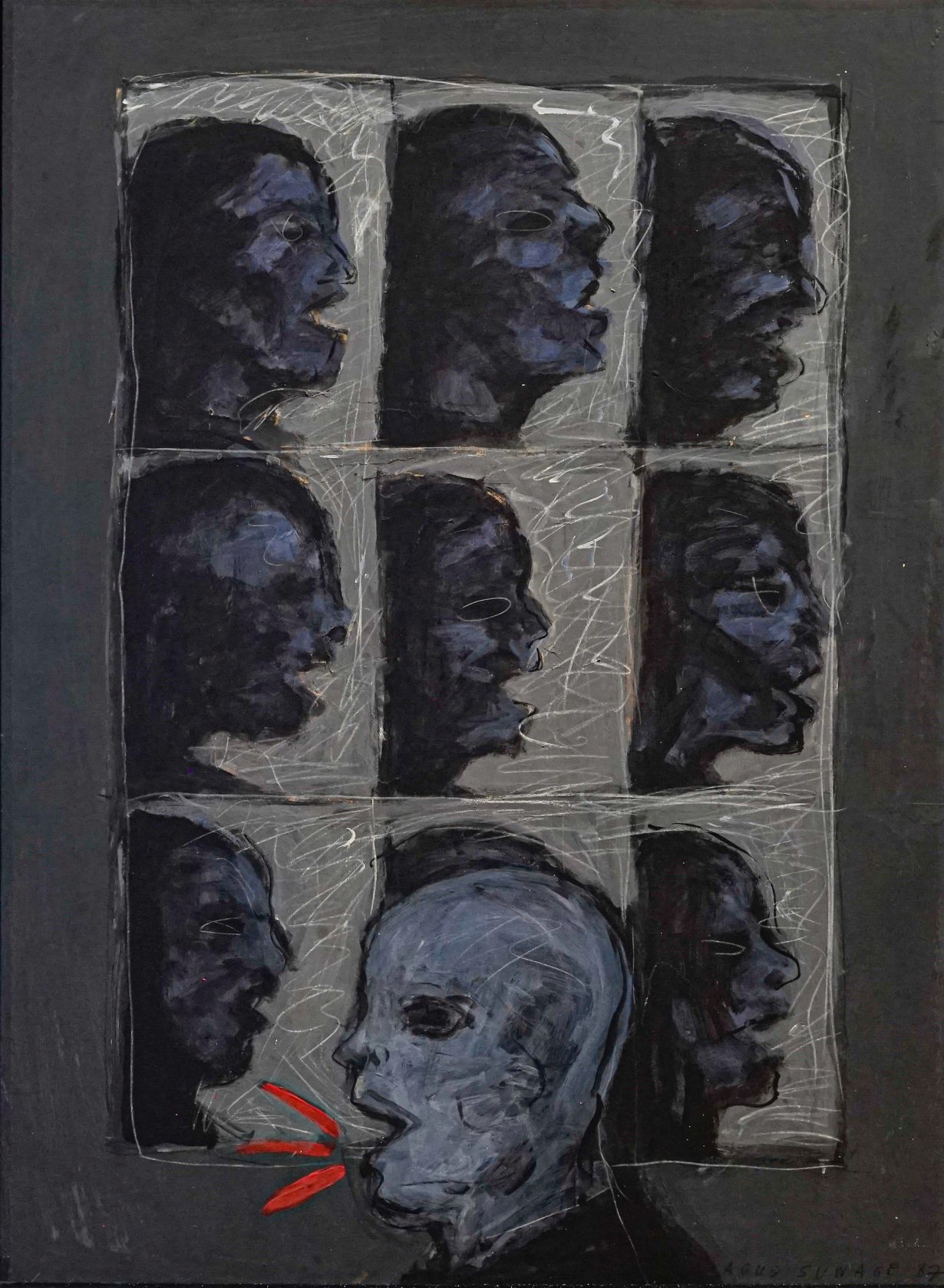

Agus Suwage, one of Indonesia’s leading artists, is known for self- portraits that are imbued with social and political commentaries. Working in painting, drawing, sculpture and installation, he started to include himself in his art during the mid-1990s, using self-portraits, he tells me when we speak in late July, as a way to critique himself before critiquing everyone else. The self-portrait, he continues, also became a space for him to make sense of the world around him, and to project and overcome his personal concerns, responses and fears in a rapidly changing society. His practice over the last 40 years has grappled with the political changes in Indonesia’s modern history, often with humour, satire and irony. Tumultuous events skewered in his works include the days of living under Suharto’s New Order regime, the fall of that regime and the riots that followed in 1998, globalisation, the rise of the internet and social media, economic crises, demonstrations, corruption, racism and oppression of minority communities.

In Agus Suwage: The Theater of Me, a survey of his works over the past 35 years at Jakarta’s Museum MACAN, one sees the changing sociopolitical climate in Indonesia through the artist’s eyes. On show are such early works as Penentang Arus (The Dissident) (1987) and Selalu Waspada (Invariably Vigilant) (1989), made when the artist was living in Jakarta and experiencing the dangers and limited freedom of society under the New Order, to more recent large-scale works like Potret Diri dan Panggung Sandiwara (Self-portrait and the Theater Stage) (2019), which comprises 60 painted zinc metal sheet cutouts of the artist in different poses – smiling, laughing, being playful. Most striking in this last work are the portraits in which he replaces/obscures his face with various objects – a gas tank, a pig, a papaya, his French bulldog, a poop emoji, a cloud of smoke. Suwage has described himself as being a chameleon, continuously shapeshifting and adapting to changing environments. In its mix of humour and satire, the installation can be read as a critical commentary on the ways in which figures such as politicians and other prominent members of society quickly change their personas and identities. The work also invites us to reflect on the multiplicity and performativity of identity, and what we choose to hide or display, especially in the age of selfies and social media.

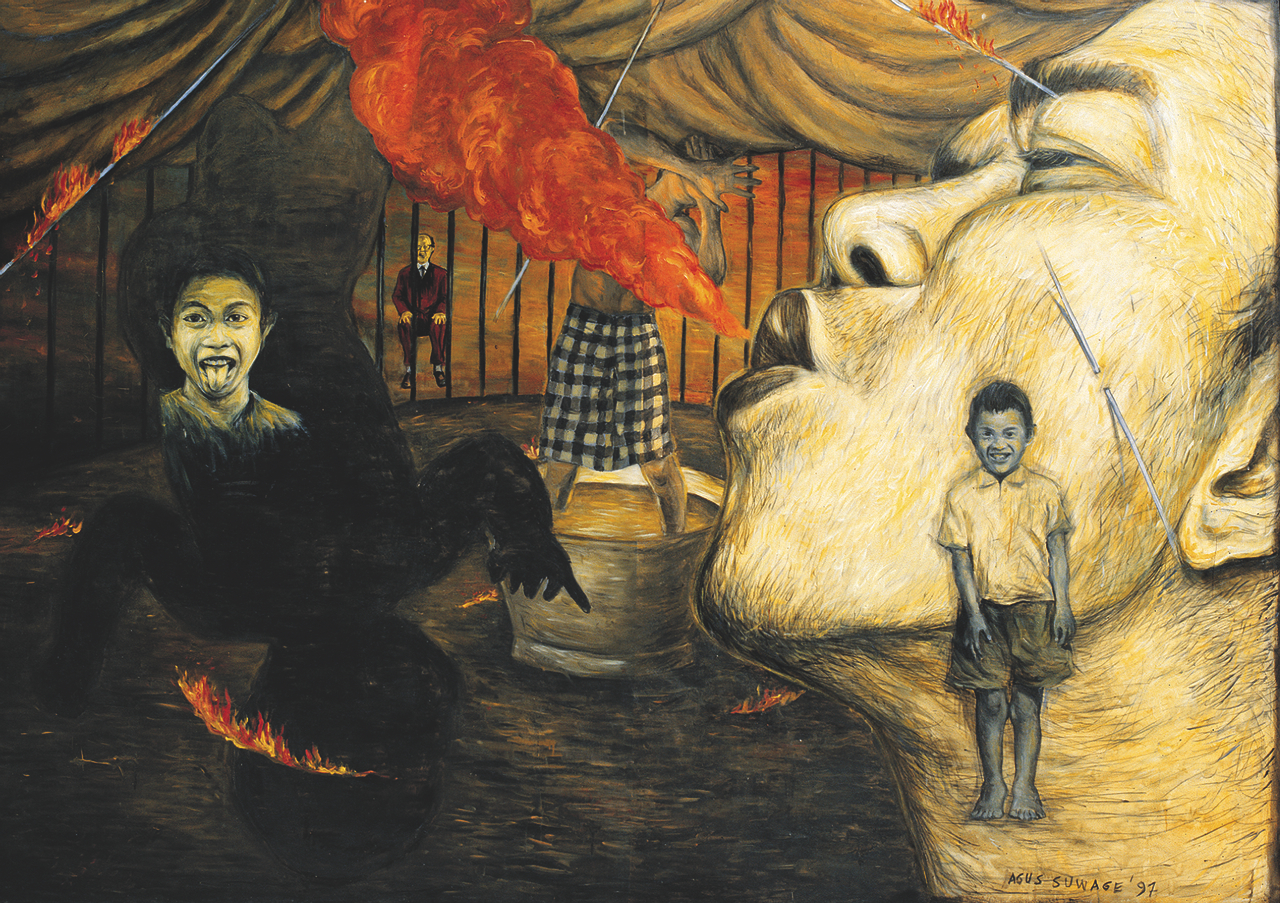

The many facets of the artist’s self are used to dramatise wider societal changes. One of Suwage’s earliest self-portraits included in the exhibition is Circus of Democracy I (1997). In this work the artist drew himself in four parts: as a baby (presented as a shadow); a child; a fire-breathing performer; and standing in a bath shielding himself against the fire. As outlined in the exhibition materials, the work depicts the cycle and transformation of the artist from boy to man, with the flames, a recurring motif in the artist’s practice, representing both danger and an act of cleansing, growth and change. In 1997 student protests broke out on the streets of Jakarta with demands for democratic reform. This was also the beginning of the Asian financial crisis, when ballooning foreign debt led to the collapse of businesses and industries, the intervention of the IMF and eventually riots and the fall of the Suharto regime. That period in Indonesian history is captured here as a kind of circus, in which the artist is at once performer, participant, victim, perpetrator and bystander. The many versions of the artist also allude to the many players within this landscape – students, protesters, the government, military and citizens. At the back of the painting is a seated man (George from the English-artist duo Gilbert & George, we’re told), suggesting that the world is watching as this social and political transformation unfolds.

Agus Suwage was born and raised in Yogyakarta, later moving to Bandung to study graphic design at the Bandung Institute of Technology (popularly known as ITB). From his early days as a graphic designer, he was interested in fine art and art history, reading and collecting exhibition catalogues for shows primarily staged outside Indonesia, he tells me – adding that one must look as much outside one’s country as within. By the late 1980s he had focused solely on his art practice and became well-known in Indonesia and internationally for his provocative and satirical works, especially the self-portraits. In addition to depicting himself, he often referenced works from Western art history, such as those by Édouard Manet, Gilbert & George and René Magritte, as though claiming a place within the broader art-historical narrative. Suwage recalls that at the time, during the mid- to-late 90s, he wasn’t sure whether his self-portraits would be well received or even of interest to the public. To his surprise, they became career-defining, when a 2001 exhibition of such works, I&I&I, at Nadi Gallery, Jakarta, sold out.

Self-representation in Suwage’s practice is not necessarily restricted to playful, chameleonic self-portraiture. He also draws from biographical material that includes family members and personal experiences. In Daughter of Democracy (1996), the artist featured his baby daughter, born at a time of political turmoil. Signalling a new hope, the child could be read as a kind of homage to the student demonstrators leading the way for change. The multimedia installation Tembok Toleransi (Tolerance Wall) (2012), Suwage says, was created after the artist’s experience of listening to a call to prayer in his residence/studio in Yogyakarta, a sound that transcends walls and other physical barriers. The work is an approximately three-by-five-metre wall composed of small zinc bricks and embedded golden ears. Each ear, concealing a speaker playing a call to prayer, invites viewers to press their own ear to the wall and listen more closely. The installation could be interpreted in response to the diversity of cultures, religions and ethnicities in Indonesia, and, in extension, to the ideas of religious tolerance and mutual respect in building an inclusive society. Suwage’s interrogation of the self in his practice demonstrates how our identities are constructed on both individual and collective levels, often overlapping with one another, allowing viewers to connect and find resonance when experiencing his works.

When thinking about the self, mortality often also comes to mind. Death is a recurring theme in Suwage’s practice, appearing most famously in his gold skeleton sculpture Luxury Crime (2009). The artist describes life and death like a cycle – where death is a part of life and they both exist simultaneously and in paradox. His interest in skeletons also speaks to notions of decay and what remains after our passing life, saying, “Skeletons are eternal… I find it fascinating that even after our existence has left this world, our physical remains, our skeletons, continue to exist and slowly persist and decay over time.” At a more intimate level, the artist says, his interest in death and mortality also projects his desire to create a legacy inspired by the Latin aphorism Ars longa, vita brevis (Art is long, life is short). Cycle in the context of the artist’s practice also relates to the repetition/reuse of materials (zinc, gold, paint, watercolour) and visual motifs, figures and themes across the breadth of his practice. The past, present and future are simultaneously present in each of his works, inviting us to think about time in relation to self, what has or has not changed, what remains visible and invisible, and our belonging to this moment in time and into the future.

Agus Suwage: The Theater of Me is on view at Museum MACAN, Jakarta, through 15 October