Alongside its refreshingly naked politics, A Time Between Ashes and Roses explores the various disconnections of the world

These days, we visit a triennial or similarly largescale exhibition to witness it proposing an argument or establishing a narrative that plots some sort of pathway through the ‘issues’ of our times. It’s no longer enough for the works on show simply to be aesthetically marvellous or even just interesting, or, as old-fashioned people might put it, ‘good’. That said, in this exhibition an extraordinary series of 27 paintings and drawings by former miner (he started that gig at the age of six) and later mid-twentieth-century-painter (he started that gig in his sixties) Yamamoto Sakubei would have you shrieking ‘bingo’ if ‘marvellous’ were on your scorecard. Art people are needy people after all; lost sheep in need of shepherding. (Yamamoto’s works, through text and image, explain the processes of mining, illustrating them as involving men, women and children – entire communities burrowing underground.)

The narrative – let’s not load it up more than that for now – of A Time Between Ashes and Roses unfolds across the work of 62 artists and collectives spread across three primary venues: the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya, Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum in Seto, a centre of the ceramics production for which this area is historically known, and downtown Seto City itself. The triennial’s title originally unfurled half a century ago in lines written by the Syrian poet known as Adonis (it was the title of a 1970 collection of his poetry), reflecting on the aftermath of the Arab–Israeli Six-Day War of 1967. Then it served as an acknowledgement of the trauma of that conflict and the potential for new beginnings in its wake. You don’t need me to tell you that current conflicts involving Israel are something more than a subplot to what’s on show here; but in case you did, the Free Palestine rhetoric loomed large in opening remarks by artistic director Sheikha Hoor, the first foreigner to direct this event.

In the exhibition itself, the sheikha – who leads the Sharjah Art Foundation and its own attendant biennials – was slightly more circumspect, using an introductory statement affixed to a wall in the Arts Center to talk more broadly about a present marked by genocides and ethnic cleansing. While not explicitly naming Gaza or Palestine (she didn’t really need to), the text did point out the equally obvious resonance of Adonis’s line with the twentieth-century history of Japan and, more broadly still, as a metaphor for humanity’s conflicted relationship to its environment.

All of the above are evidently in play in Robert Zhao Renhui’s video installation Seeing Forest (2025; an adapted version of the artist’s video installation in the Singapore Pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale), which looks at areas of deforested or developed land in his homeland that have since been reclaimed by nature: the secondary forest. The installation appears as a rubble of disintegrating wooden shelving and dried branches, bottle fragments and other detritus: as if it were a museum display highlighting entropy rather than order. The three-channel video The Owl, The Travellers, and The Cement Drain (2024) offers CCTV-style footage of wild animals making themselves at home in anthropocentric infrastructure (bins, drains, culverts) in such a way that the landscape-cum-trashscape becomes an entangled palimpsest of human and nonhuman occupation: favouring neither the one nor the other. A wall text tells us that some of the bottles and debris displayed in the installation were left by Japanese soldiers during their occupation of Malaya during the Second World War and discovered by the artist while rummaging through the forests, which serves to link violence done to nature with violence done to humans, and people to place.

Of course, the fact that a label tells us this consciously highlights the fact that the experience is museological rather than real: that this installation exists at a safe remove from the unruly world it describes. If the show, per its title, is about a space between ashes and roses, then the space we’re looking at exists between image and caption, fact and metaphor. It’s a tension that recurs throughout the triennial, notably in Mulyana’s knitted diorama of marine life Between Currents and Bloom (2019–). Featuring corals and subaquatic animals in vibrant living colour and bleached-out, skeletal versions, this presents a distinctly cute cycle of life not so far removed from a world of Labubus and Pop Mart, and perhaps offers as much succour to our trashed planet as the latter does. The aforementioned tension is more cuttingly present in works from Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographic series ‘Dioramas’ (1975–99) of displays of exotic taxidermied animals in their ‘natural’ environments at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. ‘The stuffed animals positioned before painted backdrops looked utterly fake, yet by taking a quick peek with one eye closed, all perspective vanished, and suddenly they looked very real,’ the artist said of that series. ‘I had found a way to see the world as a camera does. However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real.’ Or, these days, once you’ve made an artwork about it. Art, we’re invited to consider, often lies.

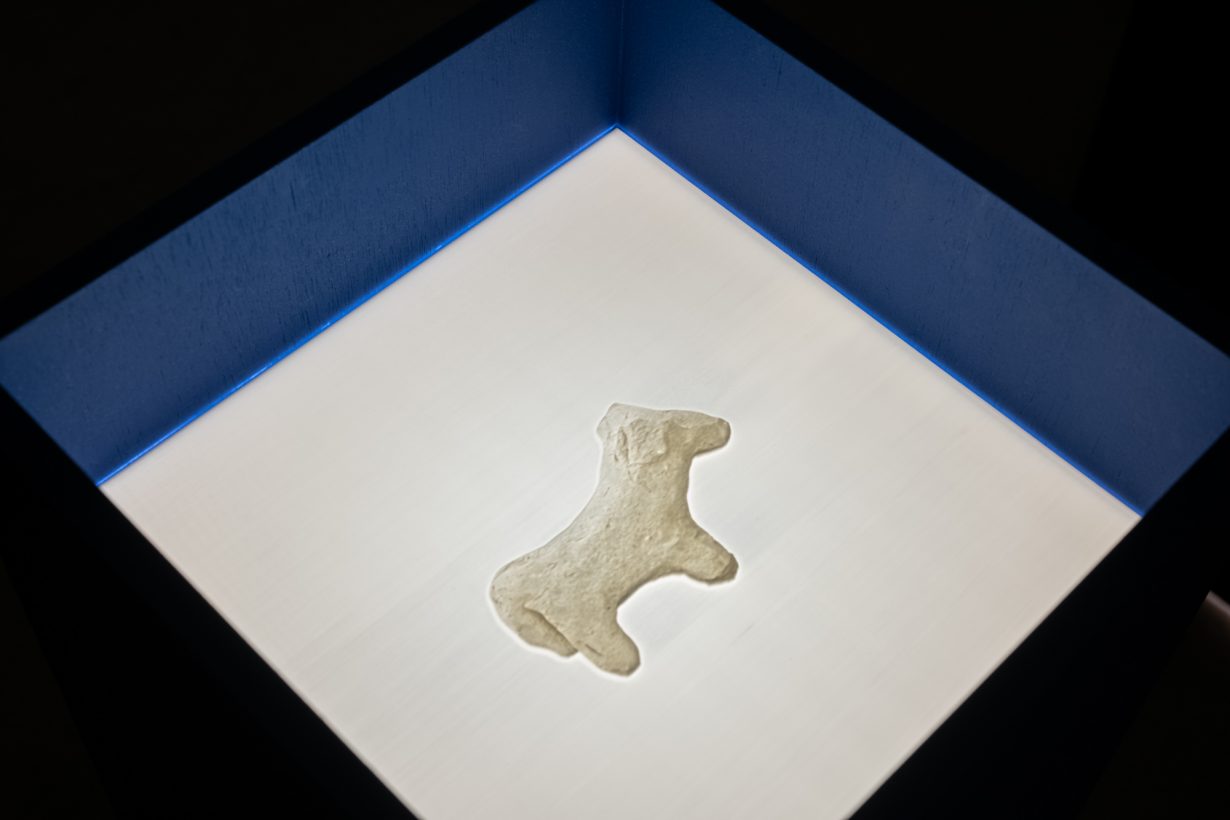

That sentiment might also be applied to Ota Saburo’s 1948 murals of animals in their natural environments for Higashiyama Zoo in Nagoya, here neatly juxtaposed with Sugimoto’s works. They were painted to make up for the fact that most of the zoo’s large carnivores had been culled during the war at the military’s request: the place now felt, according to the wall caption, ‘lonely’, as if to cure an affective disorder that exists on an institutional level. As you progress through the Aichi Arts Center, you can’t help feeling that a similar role is performed for humans by works such as Hrair Sarkissian’s Stolen Past (2025), featuring lithophanes (a translucent plaque backlit to reveal a 3D image) documenting some of the 8,000 historic, Paleolithic-era-onward cultural artefacts once housed in the Raqqa Museum and looted or destroyed during the Islamic State occupation of Syria. And if Sarkissian’s work speaks also to the human desire to be rooted (as well, of course, as the seemingly equally human desire to uproot others), then that’s something just as knowingly played upon in Dala Nasser’s largescale sculpture Noah’s Tombs (2025). It’s a deconstructed, mini ark-cum-rest stop, made of dyed and rubbed fabrics, wood and netting that collages architectural elements drawn from the three different sites that claim to be the diluvian animal-herder’s tomb. You leave the sculpture with the lingering feeling that what it really describes is some sort of human equivalent of Ota’s murals or Sugimoto’s photographs. Even if there’s no attempt to replicate a plausible ark or a particular archaeological site, the idea subsists that it’s as good as real.

A different kind of tomb forms the material for Sasaki Rui’s installation Unforgettable Residues (2025) in a former bathhouse in Seto City. There, she has installed a series of glass sheets that were pressed together around a plant and then fired so that, similarly to the nonfunctioning bathhouse, the plant was reduced to ash but its form remains. The plant species, we’re told – via a label once again – record the various eras of Seto’s development, from the pre-ceramics age to the time when the place was denuded to provide fuel for kilns, to the present. The end results look alien, like plankton seen under a microscope, and offer a similar type of palimpsest to that of Zhao’s secondary forests. Sasaki has talked previously about this type of work developing after a time spent away from Japan and a period of wanting to reconnect with her mother country. Like much of the work on show here, it disputes the colonial idea that there is such a thing as terra nullius. That’s an idea more directly attacked by Robert Andrew, a descendent of the Yawuru people of Western Australia, whose work at the Kasen clay mine takes the form of two large, monolithic lumps of Seto clay. One, What Lies Within (2025), is gradually deconstructed, so as to reveal its various strata, by a rotating string connected by a series of weights and pulleys to a loom; the other, Language in Buru (2025), is eroded by dripping water that spells out the word ‘Buru’ on its top, which, in the Yawuru language, we’re told, might approximate to the concept of land, in all its complexities. After all the captions and labels that seem such a necessary part of the rest of this triennial, Andrew’s work is refreshingly direct. You don’t need to turn the land into culture, the work suggests; the culture is in the land itself.

Aichi Triennale 2025: A Time Between Ashes and Roses at Aichi Arts Center, Nagoya and various venues, 13 September – 30 November

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next 13th Seoul Mediacity Biennale review: Spiritual science