A new show at Yeo Workshop, Singapore celebrates the ways various objects relate to one another, creating a series of fluid alliances

Singaporean artist Aki Hassan has always been interested in the idea of interdependence, how things rely on one another and nothing quite stands alone. That is why their sculptures are typically arrangements of thin metal pipes, balanced against a wall or another pipe, and whose lines flow through and around each other. Their first solo exhibition, Entangled Attachments, which features paintings and sculptures, builds on the idea of mutual reliance. The show proposes that the skilful arrangement of objects and the balancing of forces can result in beautiful new extensions and solidarities.

The sculptures here are minimal and airy assemblages of thin steel pipes coated white or brown, bent into graceful and relaxed shapes. One slouches against a wall (Tired Posture, all works 2023). Another consists of two bowlike structures interlocked (Don’t Fall). The simplest and the longest one creeps, like a young shoot of a plant, up a wall (Dyke). The various ways objects relate to one another – leaning against, propping up, intertwining – are celebrated. Here, softness is not weakness; in fact, Aki suggests that the opportunistic use of support structures allows for movement and growth. Yet these alliances are fluid and provisional, never set in stone. One careless bump can send them all tumbling down.

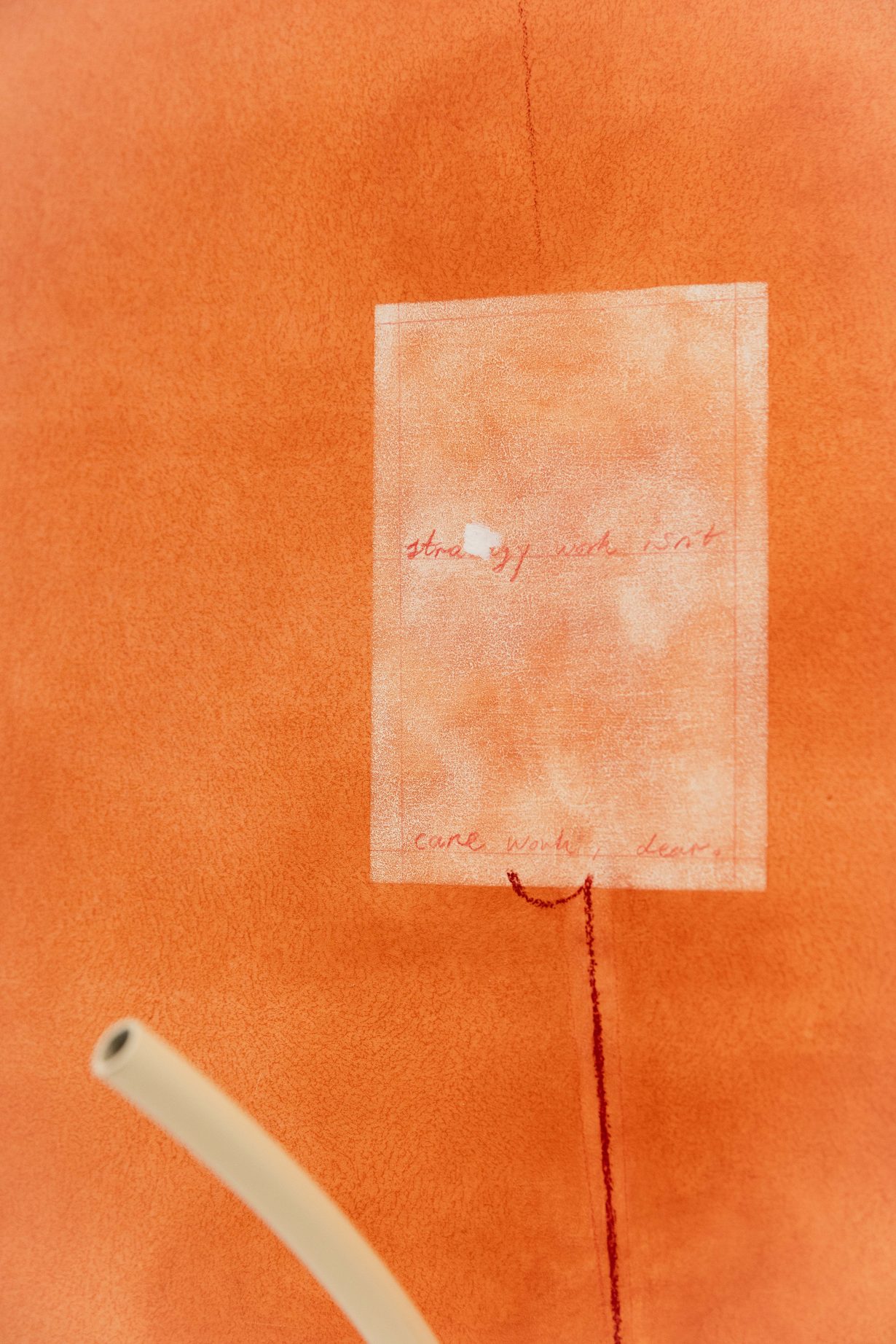

Aki, who identifies as trans, touches on trans embodiment lightly in their works. Among the abstract shapes and lines are references to the human body. For example, the pipe that extends upwards from below the painting Note for my kin suggests an erect penis. In the paintings, figuration becomes more explicit. The paintings are muted, earth-toned affairs, made up of sepia-coloured washes of pigment layered onto wooden boards. There are often gridlike compositions on them, a reference to the comics that are also part of Aki’s practice, but the squares are never perfectly aligned. Scratched out of these washes of colour are thin outlines of organic forms suggestive of fingers, breasts, buttocks, penises and bellies. These works feel carefully constructed but a little wan and hesitant, lightly figurative in a SFW way; they lack the spaciousness and presence of the sculptural works.

Nonetheless, Aki represents the arrival of an important new voice in the queer art scene in Singapore. Their voice is distinct from, say, the coded camp of Khairullah Rahim’s colourful installations that highlight the experiences of communities including drag queens and gay cruisers, as well as the highly personal and confessional performances and paintings of trans artist Marla Bendini. It is a voice that prizes subtlety, nuance and privacy – which also has some continuities with early female contemporary artists such as Kim Lim and Eng Tow, whose nature-inspired abstract work stressed weightlessness, fluidity and flow. Except that for Aki, the nonconforming body remains a persistent, grounding presence behind their elegant abstractions, and their visual style further advocates for the importance of mutual dependency and support – which makes the work relevant beyond the queer community to challenge dominant modes of thinking around the importance of self-reliance and self-help. It stresses a different sort of empowerment that says: you don’t have to do it alone – lean on others and connect in unexpected ways. Beautiful things may result.

Entangled Attachments at Yeo Workshop, Singapore, through 18 June