Unions in the US are experiencing their highest support since the 1960s. American Job at ICP New York surveys the 80 years that led to this

American Job: 1940–2011 surveys the recent history of organised labour in America using black-and-white photographs drawn mostly from the International Center of Photography’s collection. Some of the earliest of its over 130 gelatin silver prints, displayed chronologically, date to the mid-1940s, around the end of the Second World War, during which Franklin D. Roosevelt and the US’s two largest unions had agreed to halt strikes in support of the war effort. The show begins with photographs originally taken for newspapers that emphasise the size of workforces and walkouts during what the wall text calls ‘the postwar rebound of work stoppages’. In Arnold Eagle’s Changing Shift in a Shipyard (1944), a large group of men, both in and out of focus, are shown leaving work for the day; large walkouts are pictured at a 1947 rally organised by the Congress of Industrial Organisations (CIO) and the 1948 Waterfront Strike.

In particular, the exhibition emphasises the role women played in the history of labour in the US. It highlights the 1947 National Federation for Telephone Workers strike, for instance – the largest walkout by women at the time (the union was 75 percent women) – by including a photograph by Seymour Snaer of a group of police officers attempting to push a group of female demonstrators off the street. Elsewhere, a print from Nina Leen’s life magazine photo essay The American Woman’s Dilemma (1947) shows a lone woman holding a broom, surrounded by beds, ovens and washing machines, and W. Eugene Smith’s Nurse Midwife (1951) follows Nurse Maude Callen in rural South Carolina, attending to other women. Proud and glamorous female professionals in the 1970s, like those photographed by Freda Leinwand, assume a variety of roles: sound engineer, painter, lawyer, air traffic controller.

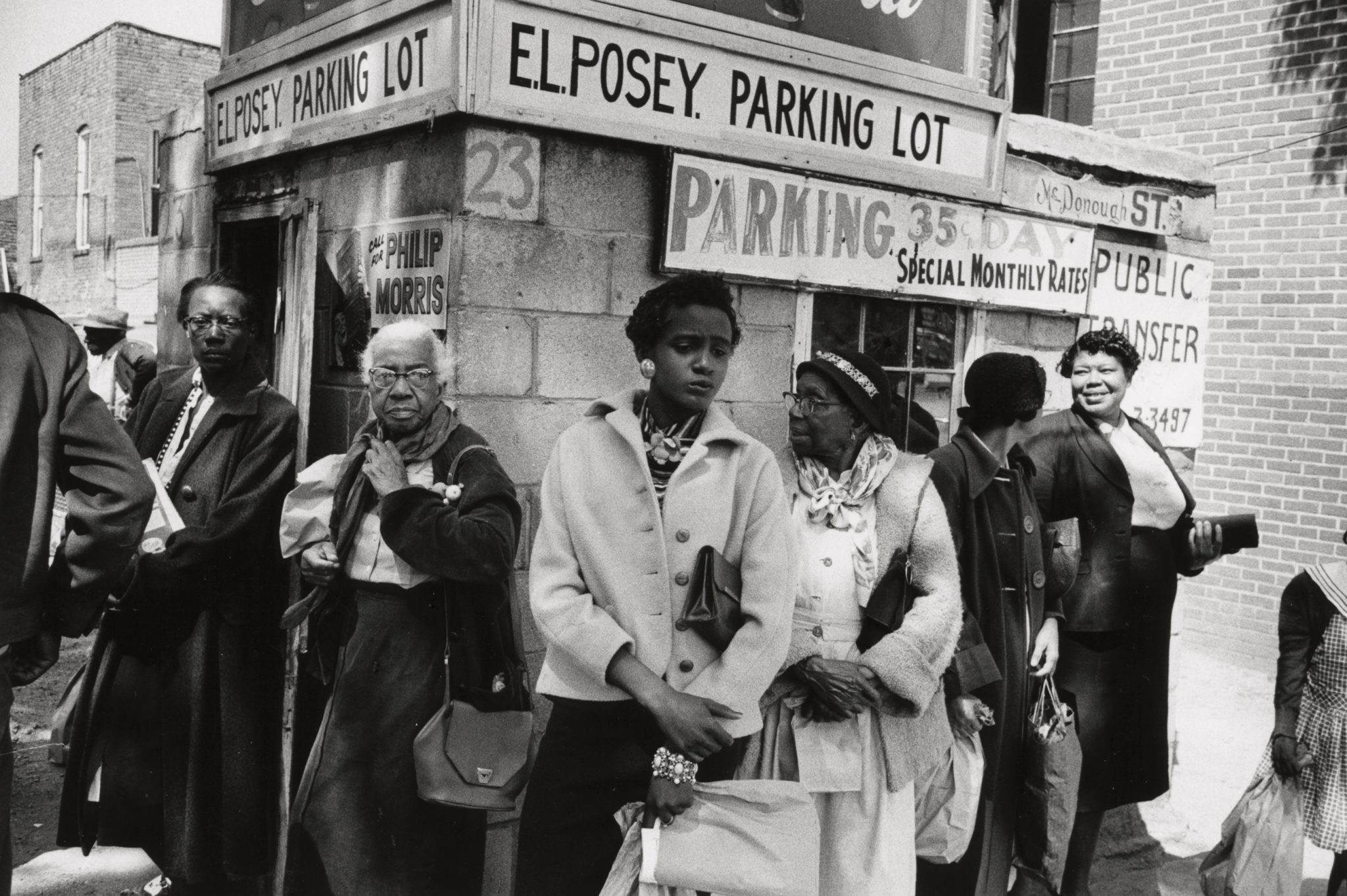

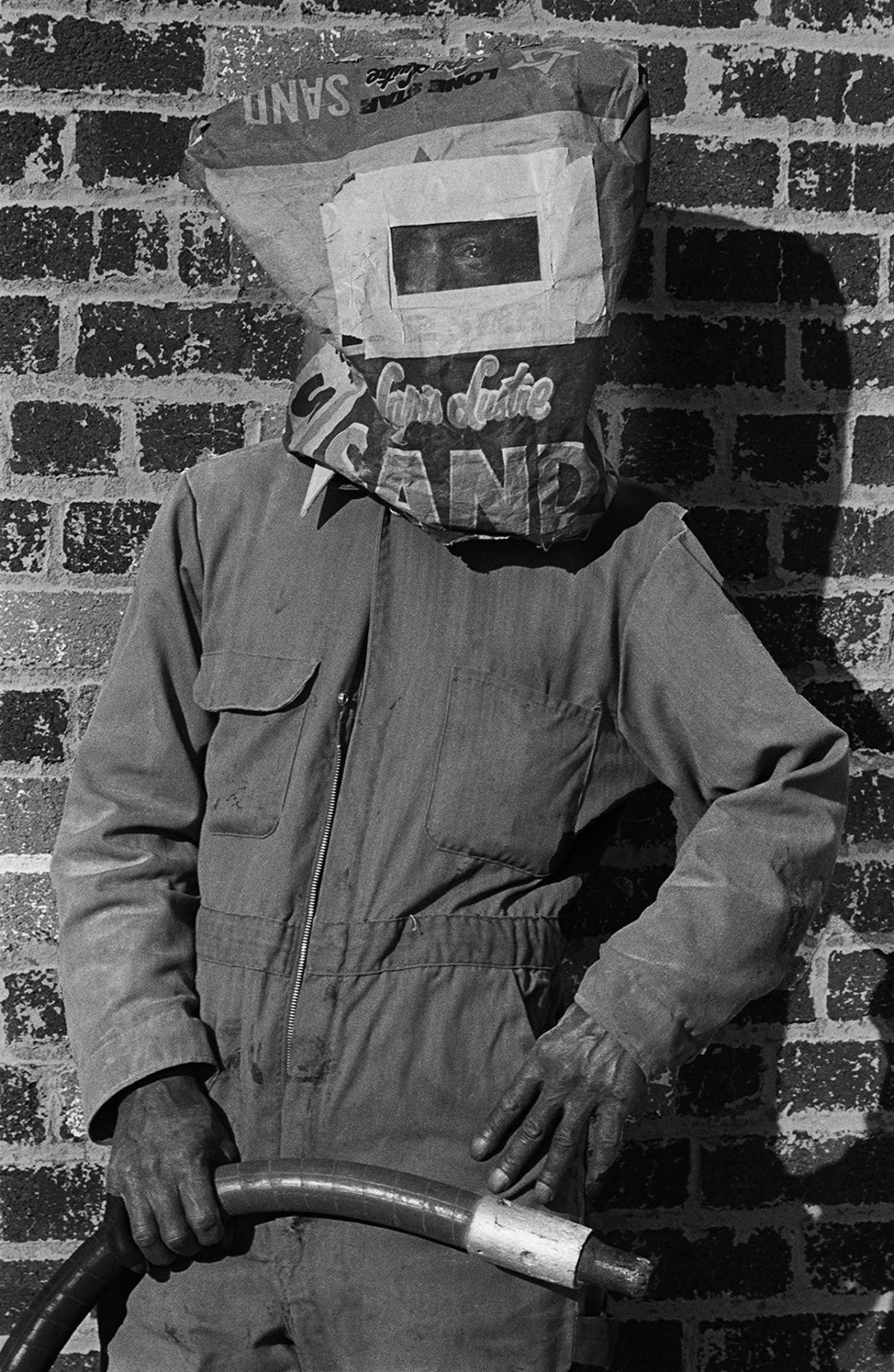

American Job likewise highlights the prominence of unions in advocating for racial equality during the civil rights era. There are photographs of the United Packinghouse Workers of America on strike for better pay; according to the wall text, this interracial union also campaigned in Mississippi on behalf of Emmett Till’s family after his murder. An image by Ernest Withers from 1968 shows African-American employees of the Memphis Department of Public Works staging a walkout after the death of two Black employees caused by a malfunctioning truck.

Following the rapid decline of industrial jobs and the union-hostile Reagan administration during the 80s, the show gets patchier. Joseph Rodriguez’s series East Side Stories (1992–2017), a visual representation of Los Angeles gang members offering a contrast to the stereotypes that circulated nationally during the 1992 LA riots – a girl leaning on a friend’s back for support, a mother and her children sitting at a kitchen table – feels like an afterthought. American Job ends with ten of Accra Shepp’s portraits of protesters from the Occupy Wall Street movement, taken in Lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park in 2011. The wall text references the 1947 protest organised by the cio, stating that both movements adopted the same rationale for organising – growing profits concentrated in the hands of a few – but it’s a parallel that doesn’t really convince.

Unions in the States are experiencing their highest support since the 1960s. Since 2011 we’ve seen the unionisation of Amazon workers, organisings in media and museum sectors, and the film industry strike of 2023. Perhaps the ICP sought not to tangle itself with organised labour’s relation to the political present, but it makes for a show that is anticlimactic when it could have been galvanising.

American Job: 1940–2011 at International Center of Photography, New York, through 5 May

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.