Hangman (2007) defies nearly all that we know and expect of the artist

Many of us are, by now, familiar with the compositional choices that have come to define Amy Sherald’s practice over the last decade or so. The artist positions her sitters at the centre of the canvas, the lower edge of which meets the body around their knees or thighs. Each figure faces us frontally and gazes towards the viewer: soulful eyes, relaxed smile, quiet confidence. Sherald is an impeccable stylist and masterfully renders the distinct textures of seersucker and satin, lace and poplin, ruched and ruffled blouses. Most notably, her sitters exist within a flat, yet vibrantly chromatic space, as she de-emphasises context and narrative and focuses our attention solely on an individual and the vastness of their humanity.

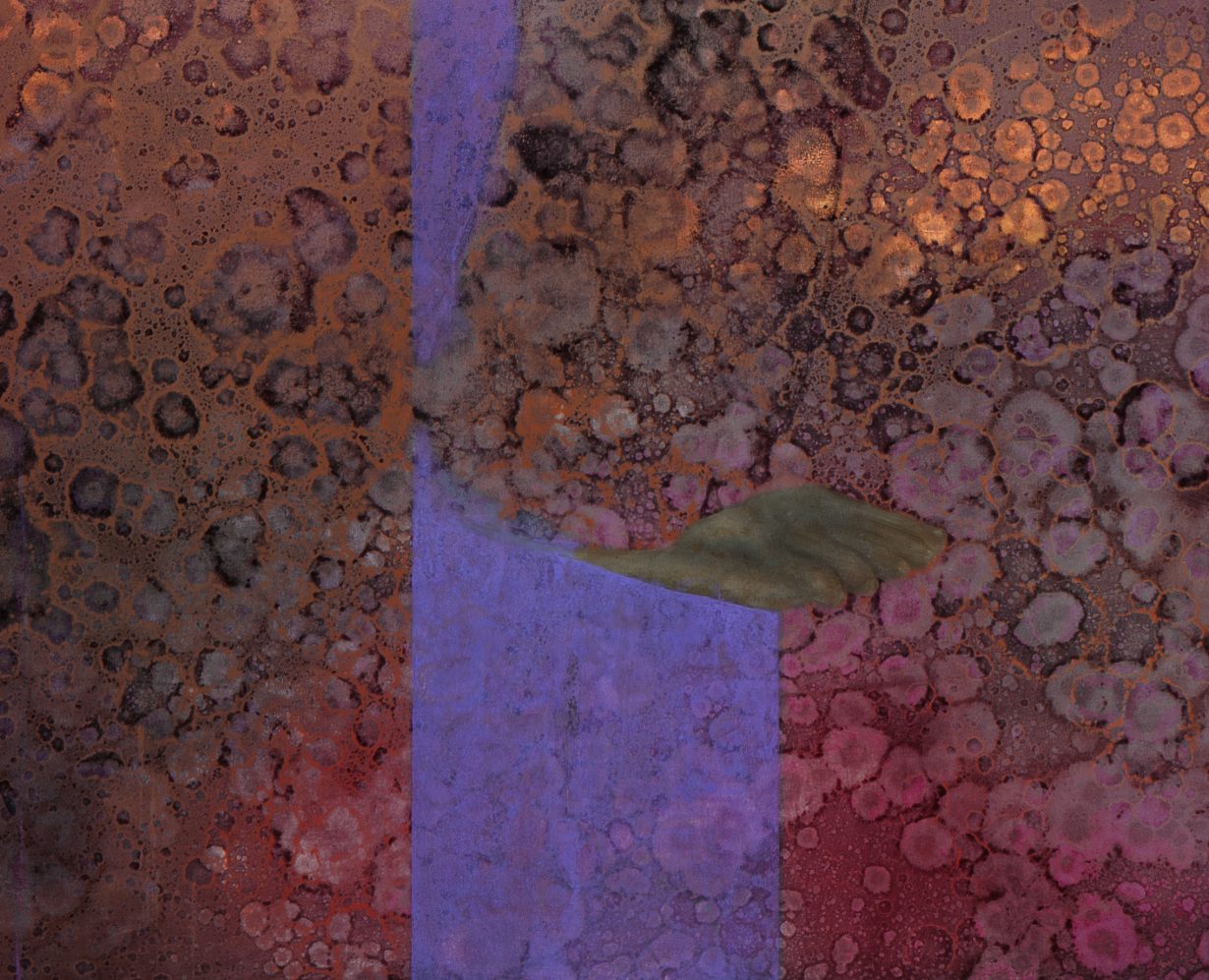

I was stunned when I first saw the artist’s 2007 painting Hangman, as it defies nearly all of the above parameters. Hangman depicts a male figure, viewed from the side. He hovers midair, just left of centre, with his feet floating impossibly above the bottom edge of the canvas. Unlike so many of Sherald’s elegantly posh subjects, he dons a modest, white ribbed undershirt and his facial hair seems about a day or two overgrown. Though the artist does not depict any instrument of torture, the pairing of a dangling body with titular allusion to a hanging tells us all we need to know. Yet the man is at peace: his eyes are closed, his chin lifted slightly, his face illuminated by soft light.

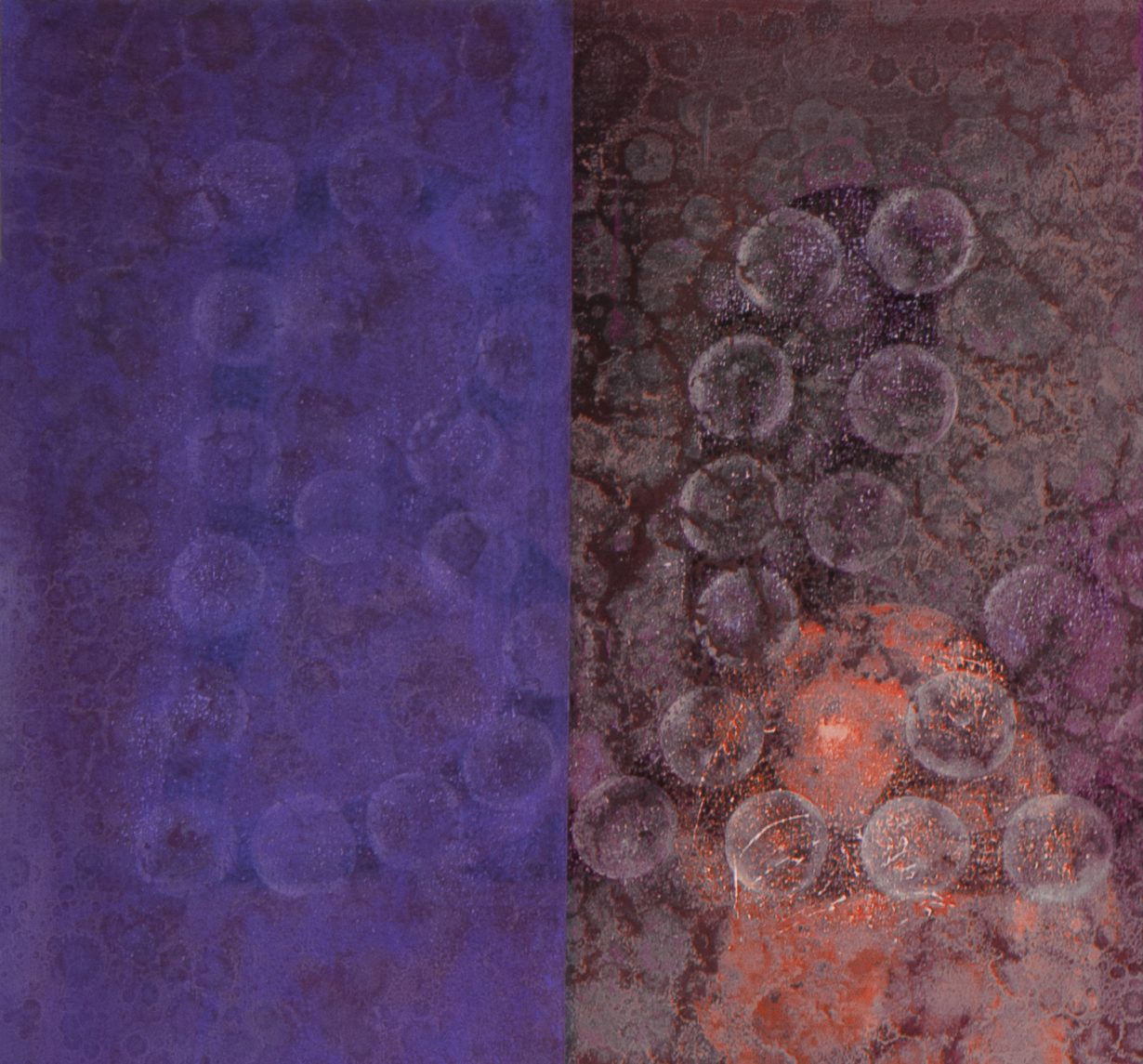

I am confounded by the construction of space in this deeply layered painting, which seems to be built up through liminal veils of pigment that rise towards the surface in splatters, like boiling water, from a subaqueous, amber depth. The man’s lower body either emerges from or dissolves into this primordial abyss, as if returning to stardust. Sherald sections the composition with four semitransparent purple columns, which create just enough contrast so that we can faintly discern at least three more bodies, trapped beneath the painting’s skein: at left, for instance, I see a shadow of one figure’s gently raised head and graceful neck, her arm falling limply to the side of her hip.

The uppermost register contains the most enigmatic detail of all. An array of circular marks coalesces into cursive lettering, yet teases the viewer with near-total illegibility. I could make out the leftmost ‘B’ and looping lowercase ‘l’ written just behind the crown of the central figure’s head. Yet I stood squinting in the gallery for several minutes, angling my posture back and forth, attempting to complete the phrase: Black Life? Black Hope? Black Magic? I go on guessing.

I remember playing the game ‘hangman’ as a kid – during roadtrips or recess. All you need is a paper and pencil. One player thinks of a word, marks out the appropriate number of blank dashes and draws a simple gallows. The other player begins guessing letters. If she guesses correctly, that letter is written out within its designated space. If she guesses incorrectly, her opponent begins drawing a stick figure, stroke by stroke, at the noose: beginning with a circle for his head, then a line for his spine, followed by each limb. The goal is to figure out the word before the figure is fully drawn – and hanged – and the game is over.

Looking back, I’m astonished by the premise of overt, unmasked violence in a children’s game, but I suppose we were all, at one point, naive to any such affect. ‘Hangman’ likely dates to seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Europe. Some accounts trace it to a barbaric execution practice wherein the condemned was offered one last chance, to play a guessing game that could potentially spare his life; in one variation, planks were removed below the condemned man’s feet with each incorrect guess, drawing out the emotional torture of anticipating one’s own death. I’m not sure if these theories hold any muster. But the Wikipedia entry for ‘hangman’ includes a newspaper clipping from turn-of-the-century Philadelphia that chronicles the popularity of ‘White Cap Parties’, Klan-themed festivities wherein attendees dressed up in white robes and masks, and played ‘hangman’ in place of, say, a round of pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey. It remains starkly evident in our time, of course, that if you can dehumanise another person, it becomes quite easy to play games – war games, mind games, power games – with their life.

Sherald has stated that she conceived of Hangman as a ‘reverse lynching’. Indeed, the alternating purple towers seem to form a row of trees cast in moonlight, while the crackling blaze of orange recalls the Klan’s ritualised violence. As in the children’s game, both the body and the written word compete for in/visibility. Yet we see no noose or gallows. Instead, the figure’s body is gracefully lifted – an analogy to the Ascension, in Christian art, rather than the Crucifixion. Saved from the earthly inferno, he rises into some divine realm.

In canonical representations of Christ’s resurrection and ascension into heaven, earthly intercessors such as the Virgin, apostles and other devotees occupy the lower register, as Christ raises his arms and soars triumphantly towards the sky, and the angels gather to receive him. The more sombre palette of Hangman reminds me of versions such as Rembrandt’s, of 1636, in which the witnesses and angels nearly disappear under a tenebristic shroud of darkness as Christ faces upwards, basking in holy light. Indeed, after completing her MFA at Baltimore’s Maryland Institute College of Art, Sherald interned in the studio of the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, whose work is marked by feathery brushwork, an aura of mysticism and moody sfumato – à la Titian and Rembrandt. Hangman has a certain place within this tradition of spiritually humanist art: it prompts us to reflect on questions of sacrifice and redemption, and to confront our own complicity in society’s many injustices. The central figure is both anonymous and familiar – but also miraculous, transmutable: one life, an entire world, a cosmos.

In the course of thinking through Hangman’s connection to religious art, I found myself compelled to revisit Sherald’s now-iconic memorial portrait of Breonna Taylor, commissioned for the cover of the September 2020 Vanity Fair. In March that year, Taylor was murdered in the middle of the night during a botched police raid – a tragic echo of the lynch mobs of Jim Crow America. Viewing Sherald’s portrait, we are burdened with the knowledge of her sitter’s untimely and senseless death. Yet Taylor’s gaze is also disarmingly present: she confronts us directly, with quiet dignity, almost as if extending us her grace. For reasons I can’t quite explain, the painting reminds me of Masaccio’s Holy Trinity (1425–27) in the Basilica di Santa Maria Novella in Florence, wherein the Virgin Mary addresses viewers and points towards her son’s hollowed, wounded body, compelling parishioners to remember his sacrifice and atone for the sins of humankind. I think of Tamika Palmer’s grief, sensitively acknowledged in the title of Allison M. Glenn’s 2021 exhibition Promise, Witness, Remembrance, which is drawn from Palmer’s reflection on how the project might best honour her late daughter’s life. Sherald’s portrait is both a lamentation and a memento mori. We cannot resurrect our own departed, but we can answer the call to collectively world a more just future.

After completing Hangman, Sherald decided not to continue the ‘reverse lynching’ series, and has since eschewed any overt reference to racial violence. Yet her practice shines a sublime light that is as powerful as any darkness, attending to the miracle of Black joy – the confident self-regard in Sometimes the King is a Woman (2019); the boyish flirtation in Handsome (2019); the uncontainable romance in For Love, and For Country (2022) – and celebrating, thusly, the promise of every individual life.

Hangman, 2007, is on view in Amy Sherald’s retrospective American Sublime, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 10 August

Allison Young is an art historian, writer and curator based in New Orleans

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.