The exhibition is taking place during a popular uprising as well as a pandemic

No one can doubt the Bangkok Art Biennale’s resolve. Its organisers, led by artistic director Apinan Poshyananda – formerly the permanent secretary of Thailand’s Ministry of Culture – are forging ahead with its second edition at a time when the country’s borders have yet to reopen to tourists in any significant way. In light of the blockbuster numbers proudly bandied about after the inaugural 2018 edition – three million visitors, according to lead sponsor, drinks conglomerate ThaiBev – this seems counterintuitive.

Adding to the cognitive dissonance are unique events on the ground: this year’s edition is taking place during a popular uprising as well as a pandemic. The streets just outside the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre (BACC), the biggest of the Biennale’s nine venues, recently saw clashes between unarmed protestors – students, mostly, calling for new elections and reforms to the constitution and monarchy – and lines of police backed by trucks spewing furious jets of blue-tinted water. As of writing, the heightened state of emergency announced in the wake of this 16 October showdown has been rescinded, but the protest movement shows no signs of abating. Twenty-five of the Bangkok Art Biennale’s artists (only eight of them Thai) have signed an open letter in support of it.

‘The theme of this year’s Biennale is Escape Routes, which according to the Biennale, explores how art can help us understand and search for ways out of the many predicaments that we are living through in the world today,’ they wrote. ‘We believe that any attempt at imagining the possible futures that lie ahead of us must begin by confronting our present realities. This means that as artists we must not only maintain art as a space for reflection and debate on the issues of the day but also be able to speak directly to the situations that have literally arrived at our doorstep. We therefore unequivocally condemn and call for the immediate stop to the use of violence against the protesters and express our support for their struggle for democracy.’

Meanwhile, the Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB) opens on 29 October at nine venues – including three famous city temples – with a ‘a line-up of 82 world-renowned artists from 35 countries in five continents, who will elevate and energize the Thai art scene with over 200 artworks’. ArtReview Asia spoke to Poshyananda during final preparations, at a moment when his conceit, ‘an attempt to understand and search for ways out of this cataclysm’, could hardly seem more pertinent or, we’re sad to say, hopeless.

ArtReview Asia Firstly, what is the BAB’s official response to the open letter?

Apinan Poshanyanda The artists have the freedom to be able to say what they wish, the right to state or stress that, as Bangkok Art Biennale artists, they are against violence. We want to stress that we too, of course, don’t support violence. More than that, we want to create a platform whereby there can be debate. Whether it’s those artists that signed, such as Ai Weiwei or Anish Kapoor or Prateep [Suthathongthai], or those that haven’t, we want to create the opportunity for them to discuss. Peace is the thing that we most long for. It all ties into our theme, ‘Escape Routes’ – how can we find a way out?

ARA How did the decision to go ahead with the Biennale come to pass?

AP It was touch and go. We were monitoring the situation a lot. We kept on hearing all biennales had been postponed or cancelled. As well as art fairs and museum openings. It was like dominos. And understandably so. I was prepared for any outcome. One option was to make it 2021 and hope that everything will be on the mend. Another was to shift a little bit but still make it 2020. But in the end, Khun Thapana Sirivadhanabhakdi, the President and CEO of Thaibev [BAB’s main sponsor], was the one who decided to go ahead. It was a brave choice.

ARA What was the rationale behind his decision? There are, of course, often annual budget timelines to consider when it comes to corporate sponsorship.

AP It’s not so much the budget. It was a matter, I think, of wanting to help the image of Thailand. Also, back in May we decided that if we wait until next year there’s going to be so much congestion… if things get better that is. Now, we’re one of the first art events in Southeast Asia to be having something happening during this time.

ARA The theme was chosen pre-pandemic, but how has it taken shape, resonated with artists since the pandemic?

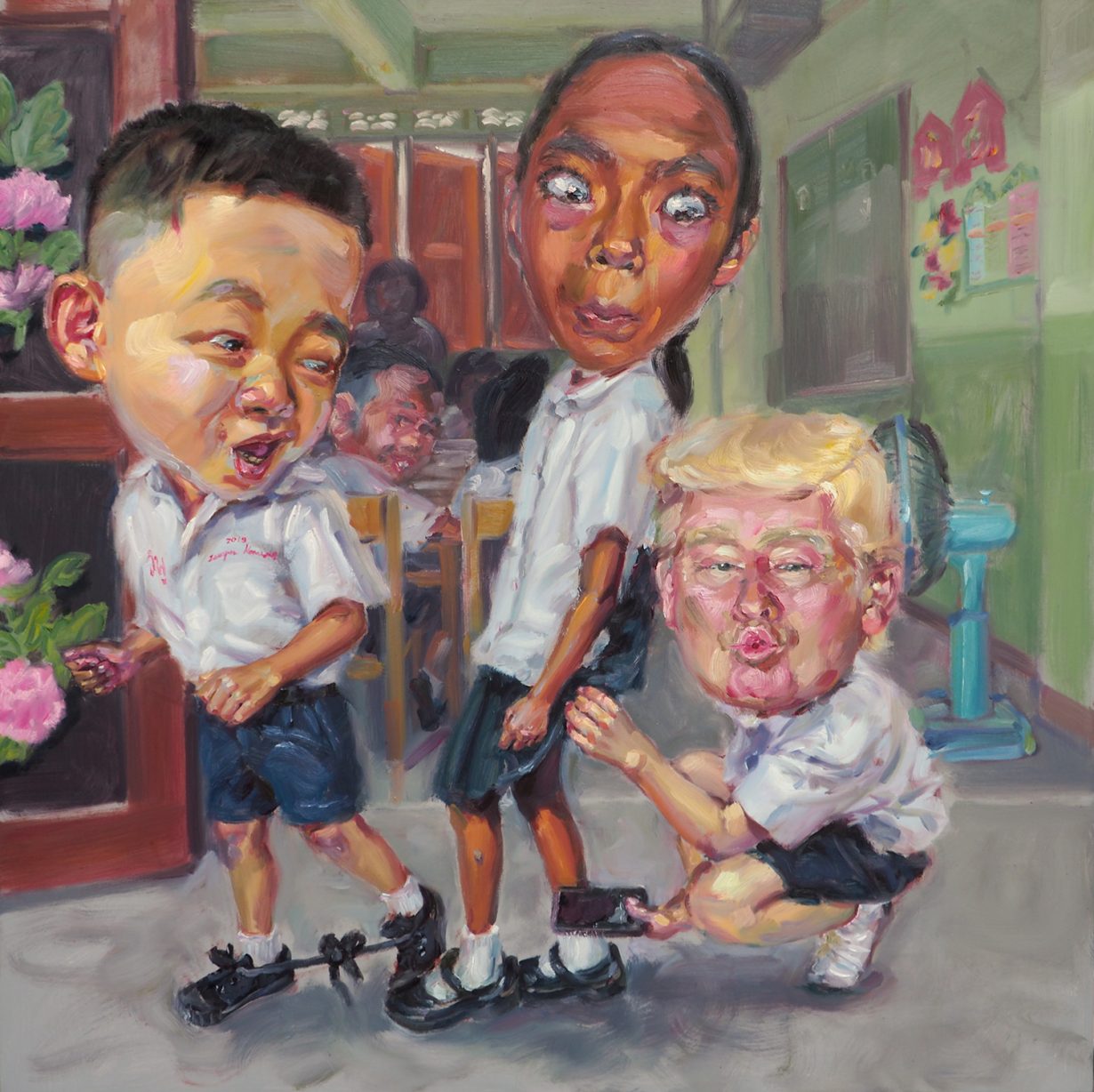

AP Last time our theme was ‘Beyond Bliss’, which implied a land of plenty while in fact what we were really asking was ‘Is the world really happy? Is blissfulness what we really want?’ And by the way, at that time we were still living under the coup d’etat government. But this time we wanted the artists to go deeper by exploring their definition of escape routes. We were originally thinking in terms of climate change, disease, migration, pollution and alienation. Those were the general parameters, but not in such a way that everything had to be so grim. We were open to the work being joyful or satirical, as well, depending on the artist. But then COVID-19 came, so ‘Escape Routes’ now has additional meanings. And now some artists are channeling COVID-19 and isolation, and angst, and even racism. So this is part of the reason why we wanted to go ahead with it now.

ARA Did many artists creating new commissions change direction after the pandemic hit?

AP Yes, you can see it in the work of several artists. Initially the theme was more connected to the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. These ask: How do people adapt to climate change and environmental crisis? It began like that. That’s why we have works such as Marina Abramovich’s VR piece about melting glaciers but then COVID-19 came and gave another aspect to the theme, and now we also have politics playing out on the streets here. Everybody is trying to escape something. Even the military are trying to escape… the military have become escapees from the trap that they invented.

ARA How have you and your curatorial team opted to arrange the works?

AP We didn’t want to box them in… Climate change, diaspora, gender, politics – all these themes are here. But we didn’t want to make one place the diaspora zone and one place the gender zone. We mixed it around. So it is not always thematic, it’s often the practicality of how to place works. And sometimes the artists also had a say.

ARA Did the main sponsor, ThaiBev, have any sway in terms of the selection process and what can and cannot be shown?

AP They never get involved. That’s the good thing. When I worked in the government, as Minister of Culture, everything we did had to be so politically correct. And in the case of BAB they just look at the works. I’m not saying that they understand everything. But they don’t come in and infringe, which is, I think, very good.

ARA But you’re a very astute and experienced curator: you know where the line is vis a vis censorship in Thailand. For example, you have talked before about the street artist Headache Stencil. If you had selected his works there would be issues, no?

AP I have sat down and talked a lot with Headache Stencil. In his case, the cat and mouse game has helped him gain fame. In the graffiti artist circle in Thailand, there’s a lot of this. You know how artists play with things. I’m not saying that he actually planned every single step, as he has gone through a lot, you know: soldiers monitoring him, following him, stalking him. But he actually went to challenge them.

We are showing works that could be considered the equivalent of Headache Stencil. But it’s a matter of explaining, of contextuality. Last time we had works that touched on Rohingya issue, dictatorship. And the soldiers came, not to monitor, but to see the show, and they took selfies standing on the ramps at the BACC with the Rohingya images. And they didn’t understand. They only saw aesthetically. We want to include messages like that, where you have to do your homework as well.

ARA Your roster of artists is skewed towards international artists, many of them big names, and more emerging Thai. What’s the philosophy behind this?

AP Well, we refuse to select [Thai] National Artists [a title given annually by the Office of the National Culture Commission of Thailand, that comes with a salary and a lifetime healthcare allowance]. They’re not up to it – I’m sorry. So that removes the seniority and takes off a load of the pressure, phone calls. So when you do that, you’re left with mid-career artists, emerging artists, some very young artists. National Artists can show anywhere. The [Thai] Ministry of Culture helps them. They have a salary, they can show abroad or here in Thailand. That’s fine. But I wanted to create a stage whereby other Thai artists can connect on this international platform.

Also, I think the art scene here has been starved of international artists, the chance to see people with stature. I’m not just saying that because they’re superstars, but at least the Thai audience get the chance to see the standard. What is the standard for them to be showing alongside Bill Viola or Anish Kapoor. It’s a big deal not just for Thai artists but Southeast Asian artists. In the future we may be more regional, but then again regional means you risk falling in the trap of the Asian miracle, where we pat each other on the back and then ASEAN [the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, an intergovernmental organisation] will move in. ‘Oh, we want to be involved’. And when they’re involved its: ‘Oh, we don’t like this, that content isn’t flattering enough, etc.’

ARA The inaugural edition of the BAB took place shortly after the inaugural Bangkok Biennial, which had an open-source format and consisted of autonomous pavilions. This time around BAB will directly overlap with the first chapter of the Bangkok Biennial. What is your take on the Bangkok Biennial?

AP Honestly, I loved it last time. Even though I was so immersed in BAB, I tried to have time to go and and see it, because it came just before and offered so many artworks. And, you know, there is cross-pollination. New Territories, the architecture studio founded by François Roche, was in the Bangkok Biennial and is now in Bangkok Art Biennale. After the Bangkok Biennial I went to see his works in the Talad Noi area and commissioned him to take part.

ARA Long before the pandemic the merits of biennials were being questioned. What do you think the pandemic has added to, or subtracted from that debate?

AP It’s shaking up the system. It’s sifting. It’s a jolt. It’s a hit on the nose. It makes us stop and think. We have to survive and survive in such a way that we make art have a message for the audience. It should be something healing, hopeful, offer something of value to its host city.

ARA Given that Thailand’s doors are yet to fully open to international tourism, are you now resigned to the likelihood that BAB 2020 will remain a local affair?

AP Yes, but we tried very hard. There have been so many attempts to get pilot projects off the ground, and we still have three months for things to open up. But plan two is to give viewers within the country, both Thais and non-Thais here, the opportunity to see our biennale. Plan three is to have online walkthroughs, that lead us through as if you are walking, so that viewers can see everything online, at all nine venues.

ARA What has it been like preparing when borders are closed and artists unable to visit?

AP What has been refreshing is that all the artists have stuck with us. They have not been deterred. All the shipping of works or live performances still went ahead. For example, three of Anish Kapoor’s assistants came and did quarantine just to install his works. And in terms of commissioned works, we’ve adapted in such a way that some works were made here. For example, Reena Saini Kallat from Bombay worked with us online using Zoom. We constructed a very large work relating to migration and the problems of the pandemic here. Digital media has allowed us to communicate from far away, and to work simultaneously. Other artists who have produced new commissions, such as Lu Yang and Leandro Erlich, came here before COVID-19. Ditto Rirkrit Tiravanija, who has done a gigantic new commission for us outside the BACC.

ARA Have there been many logistical hiccups?

AP Not many, but the installation of Anish Kapoor’s works was really, really difficult. At Wat Arun we have Sky Mirror, a beautiful piece between the temple’s prang, the giant statues and the Bodhi tree, and because it’s been raining all the time we had to put this piece up in the nighttime as the temple wanted everything clean. And we had to finish it a few days before the Her Majesty the Queen came to Wat Arun with her entourage. And at Wat Pho, meanwhile, his work is in the Sermon Hall, which is the oldest building in the temple complex, not the one with the reclining Buddha but the one with a seated Buddha. There are chandeliers, nineteenth-century lamps imported from Holland, Carrara marble and all these restored paintings. And in the middle of all this, we’ve installed Kapoor’s gigantic red wax piece, which is three tons. Because it’s a heritage building, the process has been hard. We had to cover everything with plastic sheets so the red wax doesn’t touch anything. The installers were all dressed in PPE-like outfits. It’s been fun.

ARA Regarding the temple venues, how involved are the abbots in the process of selecting and staging the art at them? Or do they trust you?

AP It was a learning process with the first BAB. But by the end of it some of them were actually giving lectures or preaching to audiences as many works were related to religion. This time around I think they know what we’re doing. We are quite sensitive about it and we respect each place.

ARA How have you enjoyed the challenge of putting a biennale together mid-pandemic?

AP There were moments when we said, ‘Oh my god, are we gonna get over this hurdle?’ But I’ve enjoyed seeing BAB 2020’s evolution and we hope to do a summary of our experiences to help other biennales in a similar situation.

The Bangkok Art Biennale 2020: Escape Routes opens on 29 October and runs through 31 January 2021