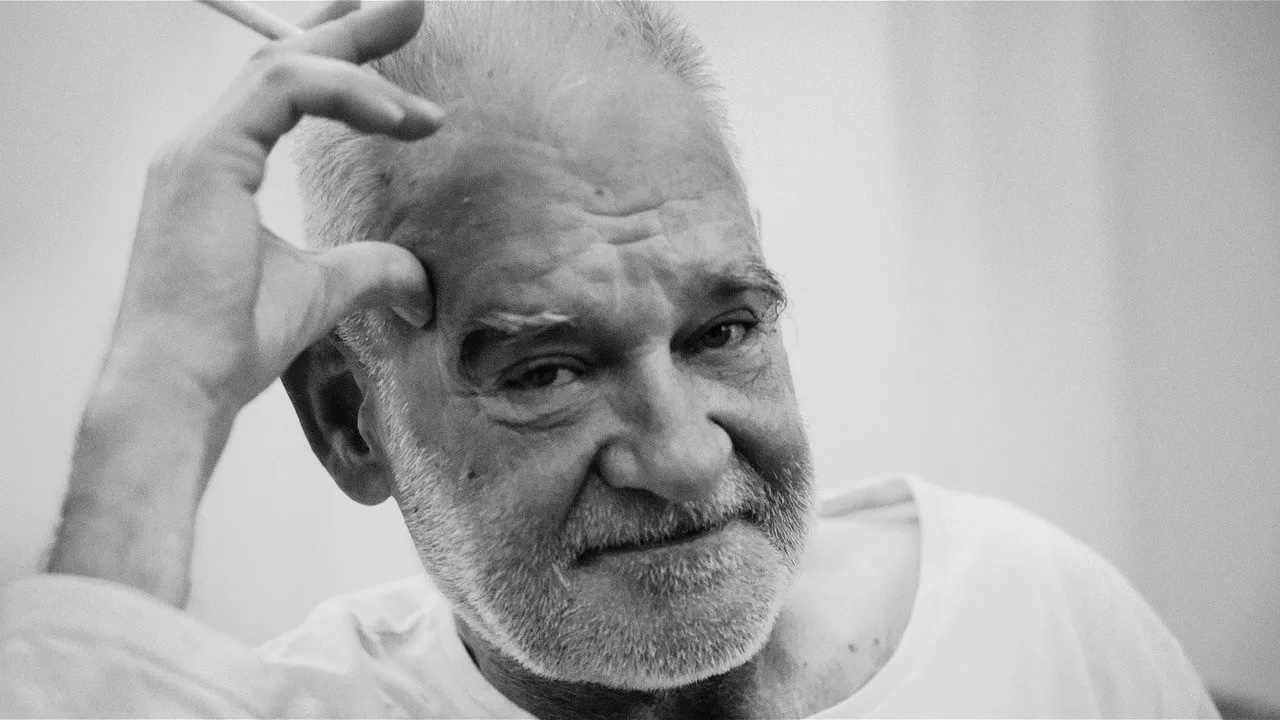

The Hungarian filmmaker, master of slow cinema, died on 6 January, aged seventy. Michael Brooke reflects on his legacy

Let’s begin at the beginning – not in the sense of Béla Tarr’s birth on 21 July 1955 in Pécs in the southwest of Hungary, but a typical beginning to one of his later films, the five made between 1988 and 2011 in collaboration with László Krasznahorkai that established him as one of cinema’s great masters. Because a Béla Tarr opening shot, typically lasting several minutes, is an emphatic statement of narrative, aesthetic, tonal and philosophical purpose.

Take the magnificently take-no-prisoners start of the seven-hour-plus Sátántangó (1994), in which an unbroken seven-minute take calmly observes unsupervised bovines emerging from a barn, an opportunistic bull mounting a bored-looking cow (presumably unplanned, but with comically perfect timing). The camera then tracks slowly – very slowly – leftwards, following the animals as they amble through what appears to be an otherwise deserted farming village, the black-and-white cinematography emphasising the textures of rusting metal, wood and mud, as we’re invited to spend a few minutes thoroughly exploring the space in which the human-driven action will eventually play out. It comes as a shock to catch up with Krasznahorkai’s source novel and clock the adjective ‘yellow’ in its opening sentence. I was one of around one hundred people who braved a Sátántangó all-nighter at the vast BFI IMAX in the summer of 2024, an experience I’ll never forget.

Or there’s the opening of Werckmeister Harmonies (Werckmeister harmóniák, 2000). Over the course of ten similarly uninterrupted minutes, some drunken, shambling barflies are choreographed by a wide-eyed visionary (Lars Rudolph was cast specifically because of the intensity of his gaze) into a working scale-model of the solar system and its irregular oval orbits. This entire sequence could be cut without affecting the film’s central narrative about a mysterious ‘Prince’, his gigantic stuffed whale, and the massed fanaticism that their visit engenders, but it establishes the overarching world-out-of-joint theme long before we get to the mid-point discussion of how Andreas Werckmeister’s equal-tempered musical scale is responsible for the world being out of kilter today.

Equally emphatic was Tarr’s attitude towards his work; in just over three decades, he made eight films, announced that he’d said everything that he wished to say, and simply stopped. Not for him the post-‘retirement’ life of an Ingmar Bergman, expanding his filmography for two full decades after his official swansong Fanny and Alexander (1982). And unlike Krzysztof Kieślowski, who died not long after announcing his own retirement, Tarr stuck around for nearly fifteen years after the February 2011 premiere of The Turin Horse (A torinói ló), enjoying life as a peripatetic film guru until his death, earlier this week, on 6 January 2026. He even ran his own Sarajevo-based film school, although he preferred to call it a ‘workshop’ and his students ‘colleagues’, echoing his collaborative approach to his own films.

They’re often described as ‘films de Béla Tarr’ as if they’d sprung from a single brilliant mind – often a misapprehension when it comes to films, but auteurists gotta, um, auteurist. But the onscreen credits usually credit Tarr’s editor wife Ágnes Hranitzky as co-director, a detail elided by rather too many Tarr commentators. The Man From London (A londoni férfi, 2007) is ‘a film by’ the pair of them, Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies are each ‘a film by László Krasznahorkai, Ágnes Hranitzky and Béla Tarr’, while the more expansive authorship attributions at the start of Damnation and The Turin Horse span half a dozen names.

Because, for all the evident loftiness of Tarr’s artistic ambition, at base his films are about small, close-knit communities, the thread that directly links the more internationally celebrated work to the scrappier, John Cassavetes-inspired Family Nest (Családi tűzfészek, 1979), The Outsider (Szabadgyalog, 1981) and The Prefab People (Panelkapcsolat, 1982). He told Hungary’s independent Partizán channel in 2023, ‘I still consider myself an anarchist’, and he loves his characters in all their misshapen squalor, while sharing their instinctive opinion that external forces of any kind are something terrifying and apocalyptic.

This is explicitly dramatised towards the end of The Turin Horse, via another extended take in which a father and daughter hesitantly venture beyond the onscreen horizon and are so horrified by what they see on the other side that they come straight back to their isolated shack with its familiar potatoes and palinka. Born a year before the abortive Hungarian uprising of 1956, Tarr lived through János Kádár’s ‘goulash Communism’, Viktor Orbán’s growing authoritarianism, and the financially devastating period of turbo-capitalism in between, so it’s little wonder that his films so frequently show people clinging to reassuring certainties. After all, we don’t have many left in this increasingly mad world.

Read next Ira Sachs on Peter Hujar