Anthea Hamilton’s art speaks the language of design. Her work is often a reconsideration of classic forms: tables, rugs, boots, tiles, wallpaper, kimonos. For her Turner Prize exhibition in 2016, she exhibited a doorway in the shape of a man’s ass, an idea she lovingly poached from the designer Gaetano Pesce. Yet this piece, like her other work, stretches design beyond its function, which is perhaps why she ultimately feels more at home in the messy experiment of contemporary art.

Hamilton refers to herself as indecisive, but her work expresses a bold freedom from any decided field. Like an interdisciplinary scholar, she slides fluidly between subject matter and source material. As with the Pesce-related work, she elegantly folds other artists into her practice, through curation, collaboration and collection. Her performance The Squash (2018) in Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries, for example, rooted itself in an old photo of choreography by Erick Hawkins to create an otherworldly experience of movement and installation. All of Hamilton’s work is a kind of collage, playing with nostalgia: a young John Travolta, the size of a wall, gazes at you; a cropped R. Crumb drawing looms overhead. As in a dream, the work’s very familiarity makes it all the more disorienting.

I spoke to Hamilton on the phone in late summer. She was warm and voluble and spoke openly about her life, while remaining at the measured distance of a business interaction. At that moment, she was emerging out of a pandemic-long hiatus from art and had just started thinking towards a fall show at O’Flaherty’s in New York.

Ross Simonini Your next show is two months away. Where are you at in that process?

Anthea Hamilton I’m always slow to start. I get tentative and nervous about committing to works, keep everything propositional and wait till nearly the last minute before diving into things. I must be waiting for a final kick up the ass to do it.

RS Do you usually need some external push to get moving?

AH I always like things really to be in dialogue, whatever shape that dialogue might be, a deadline or conversation with someone or reading a text. I’m someone who uses reciprocity to make things happen.

RS Is art communication for you?

AH I’m interested in the idea of performativity within an exhibition context. I like to use the endpoint as a performative moment, there’s a transition of performing from myself to the viewer and it’s over to them to animate the work.

RS You seem to take the audience into account quite a bit. Is that accurate?

AH I think it used to be more accurate, in the sense of prescribing what I think the audience is. For me, it’s a museum-going demographic. And maybe they’re the ones most designated to understand how they’re functioning within that space. I’m recognising their physical behaviours – how people tend to move, how long they stay within a space, how they’re being invited to think about something via information offered from the institution – and then trying to use that as material, as a way to create a framework for how a work can function. But it’s also thinking about potential audiences or those who don’t tend to go to those spaces – my shows can be designed for uses that may never occur. I don’t just mean people who might be underrepresented in gallery-going statistics but people from other places, times, animals, vegetables, and so on.

RS Is sociological behaviour an interest of yours?

AH It’s more like observation of an etiquette: recognising the patterns of behaviour but trying not to have them be too prescriptive. It was always something I thought about in a sculptural and formal way, how to scale a work to make someone look at it or stand next to it in a certain manner, or what would happen when you would make something superhuman size, and then have somebody be in proximity to it. Or what happens if you make someone peer really closely at something? Sometimes it can be a good idea to put something high up on the wall so everybody can see it, not just that person who likes to squish themselves in front of it. What if your viewing height is lower than average and you can’t see something? It’s not a fair experience for them either. So I’m just trying to offer different types of people different experiences. I tend to lead with the visual but process it alongside the other senses.

RS When you find an image that compels you, is your first instinct to use it?

AH I used to see everything as an image, whether an object or a space, and what was pertinent about images is that they had edges.

Plus I was interested in what fell outside of their visual space. But I don’t necessarily think in images now. I’m trying to think about what happens when I take that kind of framework and zoom out and go extradimensional. Like how can those sensations or that kind of methodology work when I step further back?

RS What do you think about originality? Does it matter?

AH I’m more aware of the term ‘ownership’, and that maybe something was made by someone else’s hand. And perhaps that loops back to the idea of performativity and the multiplicity of perspectives. Because the search for originality is quite exhausting. Normally what happens is that there’s something in the air, people feel it and make it present at the same time in batches of responses but only one or two may be declared of the author of that moment. Novel things happen in waves. I find it hard to separate readings of the term ‘original’ from a territorial, divisive attitude.

RS If you were working on something and then you saw someone else was doing something similar, would you change what you were doing?

AH When you’re at art school, it’s very much about staking your own territory. Like, these are my tools and this is what I’m going to do, and these are my signatures and this is my brand. That very much seemed the language, and competitiveness was actively encouraged. But normally, if you had made the same thing, the reasons why were driven by different ideals. Or, inversely, you might share an ideology and that competition was there as a destructive move to stop alliances forming. Whatever it was [you made], it was just the right object at that time in culture and had a capacity to speak in a number of different ways. So I would be wondering whether what I’m interested in is just participating in the contemporary conversation, or whether the work itself was significant.

RS Has this happened to you?

AH Many times. The thing wasn’t important – on one occasion just a cigarette – but it kept appearing in people’s work. I realise I wanted to engage in a current conversation, to say hi and be friendly somehow. It entered the work at SculptureCenter [in Cigarette Pipes, 2016] as a pipe work in the courtyard. And maybe I just needed to get through it, you know? It supported me through that moment of wanting to make that work.

RS That’s such a nice, noncompetitive perspective.

AH Yeah. Maybe that’s a thing of being a bit older. My battles and ambitions lie elsewhere now. A notable artworld figure once said to me that the first ten years of working as an artist is a gift. Does that imply that you only have ten years’ worth of ideas within you? My first ten years is already up. I expect that person was trying to psych me out.

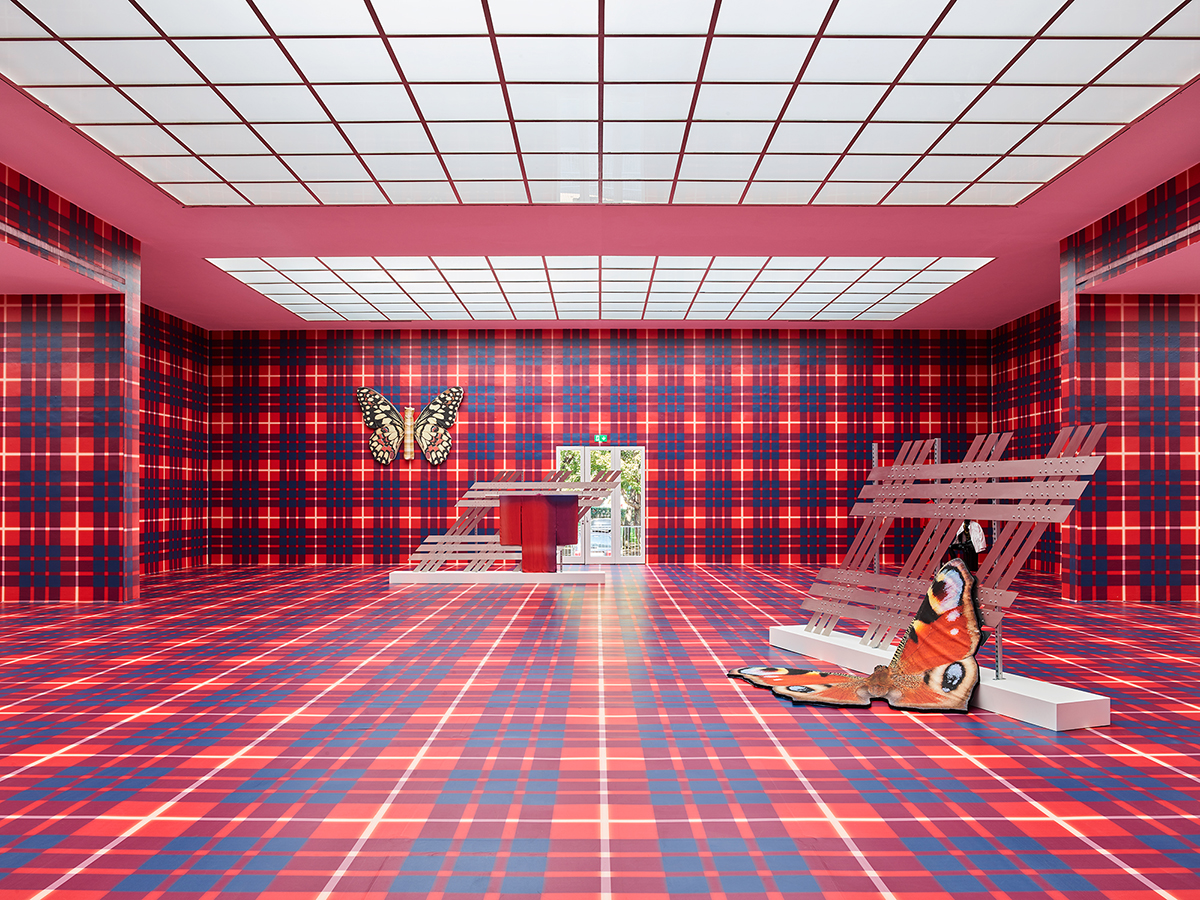

Anthea Hamilton: The New Life, 2018 (installation view, Secession, Vienna). Photo: Sophie Thun/Secession. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery, London & Naples

RS You return to some formal ideas, like the various kimonos you’ve made, but not others, like the cigarettes. What brings you back to an idea?

AH I can be super uptight when I’m really agonising over what things to do. I try not to declare myself indecisive because I feel that’s negative, but it probably appears to people I work with that I’m incredibly so. For instance, it took a month to decide the width of grout for The Squash at Tate Britain. It was only a millimetre’s difference, but it was important to me. It was a vast space, so the decision would have equally vast impact, and resonance. It needed that level of care – the performers would have been framed poorly otherwise, and therefore they’d be compromised.

So how that lives in the work is that things are associated with freeness. A kimono, it’s like somebody in LA walking down a glass staircase, just out of the shower, and they wrap themselves round in it: it’s silky, it’s chic, or it’s like the kimono-wearing geisha, who’s been declared by others as a site of sexual freedoms. The kimono has been so battered culturally, but it doesn’t ever lose its formal shape or visual impact. It’s a very stable object, I think. That’s why I come back to it. It can deal with whatever kind of absurd combination of imagery I might place on there.

RS How do you end up making grout-level decisions?

AH Oh my God. Usually someone’s messaging me furiously saying, ‘We need to know now’. And this forces a moment of epiphany, when I can recognise what decision to take to make the objects or materials perform as the most like themselves. And it turns out that five millimetres was the answer in that situation and the use of the black grout with white tiles ties the work to Superstudio’s Quaderna works, [French Nouveau Réalisme sculptor] Jean-Pierre Raynaud and cheaply installed municipal bathrooms. I think people may assume that the work is just quite visual, but really I’m just working with images to make other, nonvisual activity happen.

RS In retrospect, do you usually feel as if you’ve made the right choices?

AH I’m happy if I’ve finished something, but really finished it. I want to know I’ve considered something all the way around, inside and out. If I have to rush something, I just can’t enjoy it, even if it works. Because it would just feel cheap.

RS Do you get decision-fatigue in your daily life?

AH Oh, totally. I was decisioned out for quite a while for a couple of years or so. It was horrible. I’ve been working on the new public garden for Studio Voltaire in London, and when the invitation to take part in it arose I felt it would be really healthy to work on a garden because, you know, gardens are meant to be restorative, a site of sanctuary. But it was the same problem, just in a different format. It was decision-making fatigue and also infrastructural mess but with horticulture rather than fabric, tiles, press texts.

RS You can’t escape yourself.

AH That’s why I like to collaborate with other people, seeing how other individuals or industries make decisions, or what a decision is constituted from, or how it behaves in another field. Decision-making itself is a practice.

RS Do you live by a schedule?

AH At the moment I wake up early and have two hours of reading in the morning: summer schedule. I have a young kid and they have their own timescale that doesn’t map easily onto anything else. It requires a shift in what the creative process is.

RS Has parenthood affected your art?

AH So the first bit, when I was a new mother, was wild because there were a lot of hormones coursing through my body as a consequence of the very extreme, physical act in giving birth. There’s a lot of adrenaline and so I could get a lot of stuff done. Biologically, all was in place to protect the newborn: I was like a cavewoman, ready to fight off sabre-toothed tigers. My peripheral vision was increased, it was as though my eyes were on the side of my head. The notion of hours and minutes disappeared and time for me was wholly psychedelic. So it was a very free period because everything was totally deregulated. Several years later things are more institutionalised.

RS I often think about the monastic life and how every decision is already made for you, down to the foot you use to cross a threshold.

AH I’m literally thinking about monasteries and convents here: I romanticise that there’s kind of a decadence to that life because it’s so set. Like, you’re in a state of constant focus and holding oneself on a limit of rapture for even the smallest decisions or acts. You’re close to the edge all the time. Hormonally, it must be a really extreme space.

RS You play with the idea of being an artist and a designer. Do you see a distinction between the two?

AH I was recently speaking with someone who’s a product designer and felt they used a different vocabulary to how generally artists tend to speak, a different methodology of decision-making and solutions. The ways in which design problems are identified and resolved seem to exist quite differently to the way that artists deal with problems. And so, even though I agree with you that my practice maybe is quite blurry with regard to design, I think it is very much playing at it, like dressing up in the idea of being a designer. Because my problem-solving methodology wouldn’t make any sense in practical, structural terms. The physics wouldn’t hold up. Things I produce are often physically unstable – even relying on a precariousness of equilibrium – because I’m interested in the image of a solution or the image of a question, or how one asks the question. I feel like the work I’m making is just about making public the questions that are going through my head, rather than solutions.

RS What was the design vocabulary you mentioned?

AH This is based on a couple of conversations with individuals, I’m not trying to declare this as an absolute truth but they often spoke about this term ‘story’. Like, what is the story for this? And while I’m working quite logically through issues, the design process seemed to be more about narrativising situations. I’m almost more mathematical, or wishing to be. As a kid, maths was my absolute favourite subject – I loved it, I was very attracted by the idea of making things equal. It was about being logical.

RS Do you use systems in your work?

AH Mathematical is probably not the right term for it. It’s just about a sense of satisfaction when a conclusion is reached. There is no hidden technique to my process, but normally a system becomes clear to me in how I’m trying to understand things and I can fundamentally recognise myself in it all. I don’t think in a sequential way, which is why the work is the way it is – I want everything to happen at once. I can’t comprehend how you could possibly know how to have one thing before the other.

I wanted to make films, be a movie director, but still now I puzzle over how one would know what frame follows the next one. In fact, I’m more interested in the transitions in films rather than what the content is. For me it needs to be one big thing that happens all at once, a state forever finding its own forms and adapting to variables. Maybe it’s like when you see a big sum on a board: it’s all there.

Ross Simonini is a writer, artist, musician and dialogist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object, Verb

From the October 2021 issue of ArtReview