In troubling times, galleries serve up soothing variations on the familiar

The timing of this year’s Berlin Gallery Weekend (29 April – 1 May) was evidently a no-brainer. Its 52 officially participating galleries – plus all the other venues that smartly synced their openings, from scuffling off-spaces to institutions – unveiled new presentations right after the opening festivities of the Venice Biennale. This, of course, invited art-addicted collectors and unwearied international art aficionados to keep partying, spending and, on occasion, soaking up more work by Surrealism-inclined women artists (we see you, Meyer Riegger, with your Meret Oppenheim and Eva Koťátková shows), while bathed in the loquacious afterglow of the first big art event in a while. The organisers’ sneaky plan to seed the Veneto’s clouds before welcoming guests to a suddenly sun-splashed Berlin appears to have worked nicely, too. And at one early opening at least – for the Italianate group show Opera Opera at Deutsche Bank’s Palais Populaire (the exhibitiontouring from Rome’s MAXXI) – Aperol spritzes were again poured out, in case anybody missed them.

Mostly, though, the galleries stayed classy, some offering up relatively thorny and slow-burn fare. Galerie Buchholz, across two spaces, delivered a characteristically oblique and context-free suite of murky, occulted, X-ray-like monochrome photographs by Trisha Donnelly and a febrile, omnidirectional roomful of early works (from 1967–78) by fellow Bay Area non-rationalist Martin Wong, somewhere between funky, lopsided, brown-toned Pop and Blakean rapture: ceramics of angels, winged Coke bottles and laughing coyotes, line drawings of vernacular American architecture and scroll-like text works. At Esther Schipper, David Claerbout’s two glacial video works could be patiently parsed in visual terms – one presented a plane in a hangar, the other a plaintive meld of archival and reconstructed imagery of urchins and down-at-heel adults – though the dense thematic, something to do with the hemispheres of the brain, was even slower to clarify itself.

The components of Claerbout’s show that collectors, as opposed to institutions, were likely to snap up were accompanying drawings featuring the same imagery plus faintly self-conscious, aide memoire-like scribbled notes about the films’ production. This canny format, recalcitrant moving-image plus impulse-buy goods, was redoubled in Konrad Fischer’s Bruce Nauman show, where the black-and-white video Practice (2021) got its Berlin premiere. While inspired by a contract signed by a Canadian government representative and marked with an ‘X’ by a Blackfoot chief who seemingly couldn’t write or read, it finds the octogenarian artist running an elegiac, late-style variation on his repetitive-action wheelhouse as his own body slows, his puffy paw tracing one laborious movement on a scarred table over and over. Upstairs, the gallery – digits evidently uppermost in the mind – saw fit to accompany this with a saleable ragbag of seemingly any smallish work available by Nauman featuring hands. If you weren’t shopping, at this point you might have thrown up your own.

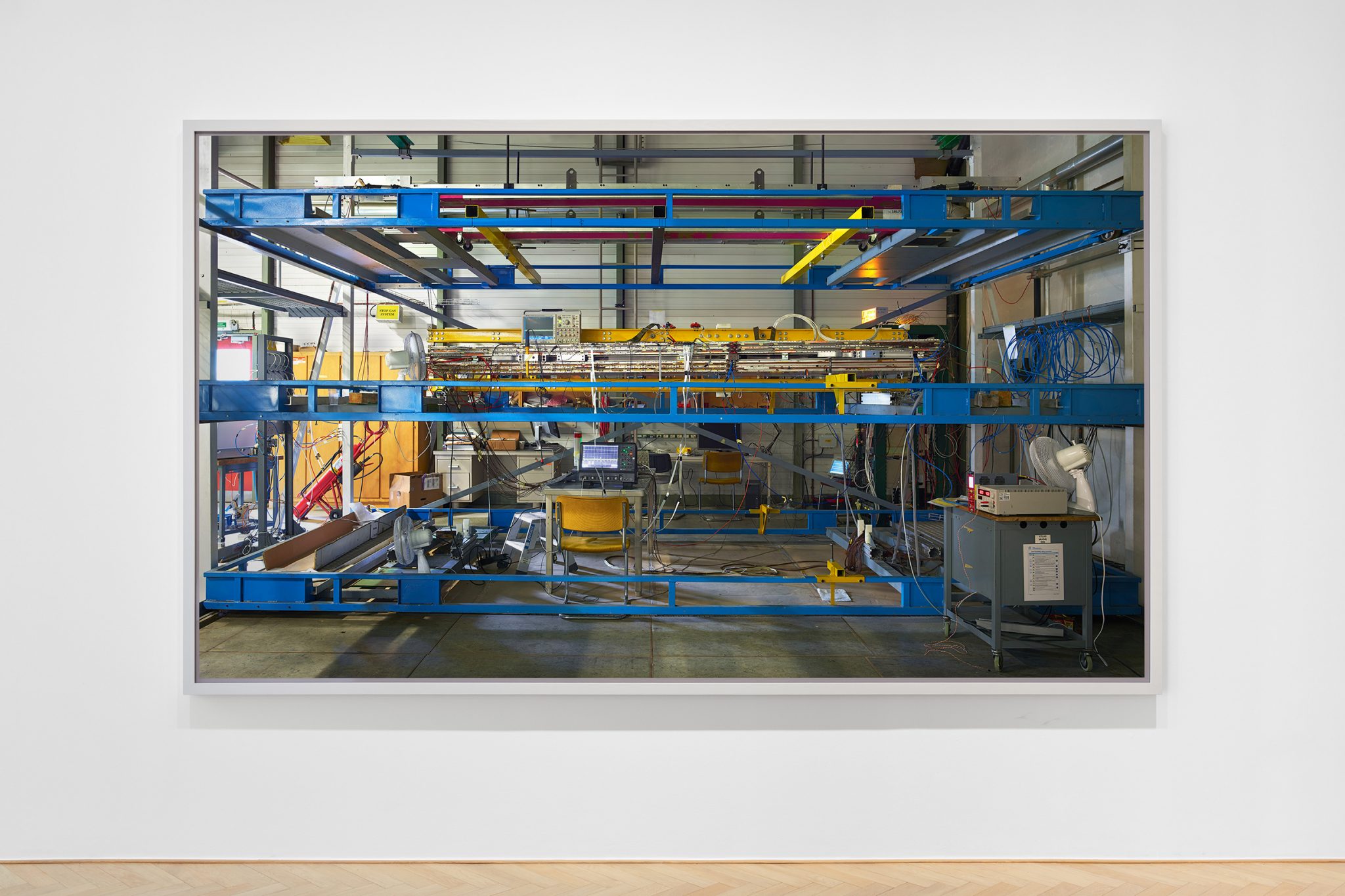

Other galleries and their artists skewed, at a tumultuous time, to grounding and even soothing variations on the familiar. At Barbara Wien, Haegue Yang offered manipulable globular objects festooned with miniature bells plus some tight, satisfying cut-paper collages; at Max Hetzler, Thomas Struth offered familiar yet often downright luscious evidence that he’s not yet done photographing front-facing family groups or incomprehensible, gee-whiz tangles of cabling and electronics at CERN. And if you thought that the venerable Thomas Bayrle, here inaugurating a new space for the historically expansion-resistant Neugerriemschneider, was going to pivot away from print-ready compositions made up of myriad miniaturised images that speak to latter-day humanity’s almost mystical relationship with industrial production, then I have the proverbial bridge in Brooklyn to sell you.

There was, nevertheless, scratchier fare on display elsewhere. Joan Jonas’s overhanging field of Vietnamese bamboo kites, activated in the mind by their animist title, Draw on the Wind (2018), dominated her show in the relatively new, low-slung space Heidi. At the Berlinische Galerie, Nina Canell’s show centred on the self-annihilating Muscle Memory (7 tonnes) (2022), a large, floor-based expanse of seashells that the viewer crunches under their feet, ideally while considering that such natural material, ground up, is a core element in concrete and thus our urban reality. At Tanja Wagner, Anna Witt set up sometimes live, sometimes recorded, and rarely wholly restful detournements of autonomous sensory meridian response, aka ASMR, oriented towards amplifications of soft sounds made by destroying something, eg a dried-out plant.

Tension, destruction, the desire for calm: these conditions, particularly now, are the backdrop for daily life, though at this Berlin Gallery Weekend they were often the deep background. Despite displaced people arriving daily at the city’s main train station and flags of solidarity draped over museum facades, not so many participants here felt duty-bound to say anything about Ukraine, and uneasy justifications might easily offer themselves: it’s been a tough few years market-wise and we need to make some money, art isn’t about daily politics, etc. Sterling Ruby and Sprüth Magers, who are probably both doing fine, broke the conspicuous silence that dominated commercial spaces: while showing ceramics and oversized textile works inside, the American artist plastered windows with a yellow and blue purchasable edition (reading, and sending an itch to the brain, ‘WAS WAR WON’) aimed at benefiting Be an Angel eV, a charitable organisation working with refugees, many of them now coming from Ukraine.

Supporting the same org was the recently reopened Neuenationalgalerie, which not only launched a Barbara Kruger show – her trademark boldface text installation covers the floor, effectively invisible if you’re passing by, includes the endlessly timely George Orwell line about totalitarianism and the boot stamping on someone’s face forever – but presented a week of daily performances of Crimean-born artist Maria Kulikovska’s 254. Here, for an hour at a time, in a sanctioned reconstruction of her samizdat, arrest-causing performance in 2014 at the opening of Manifesta 10 in St Petersburg, Kulikovska lay on the steps of the institution wrapped in her country’s flag, like a covered dead body. (The title refers to the number she was given after Crimea was annexed and she became a refugee in Kiev.) Such gestures of solidarity and awareness- and fundraising aside, much of what was on display during this Gallery Weekend swung, predictably, in wholly different directions. There were the pleasures of the known and unknown; the expected cascades of figurative painting; the repeated sight of artists pursuing their long-term hermetic obsessions; the citywide spectacle of a commercial art scene pulling together and piggybacking. And, amid all of this, the compound – and complicated – illusion of business as usual.