When Wilhelm Sasnal’s face pops up on a Skype connection from Kraków, he’s just returned from the Berlin Film Festival, where he and his wife, Anka, premiered Huba (Parasite, 2013), their third feature film collaboration. He’s about to edit some short 16mm films for Take Me to the Other Side, an exhibition at Lismore Castle Arts, County Waterford, Ireland, themed around Hans Christian Andersen. He’s also apportioning time, 13 years after he drew artworld attention for canvases that enlarged and isolated mute details from Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991), to one of his own graphic novels, a mix of fact and invention concerning murder and suicide in Hawaii. And following a gap of two months, he’s about to get back to painting, a prospect he’s evidently relishing.

For other artists, such a footloose stylistic approach might be the headline. For the forty-one-year-old Sasnal, one of the most assured yet mercurial artists of his generation, it’s a sidebar. Yet a relevant one, because his art emerges from an abiding sense that, in terms of the culture of images, everything is levelled, everything can slip contextual bonds, everything can speak in troubling depth.

This goes back. Picture Sasnal, a young metalhead from Tarnów, Poland, seeing album covers for Slayer’s Reign in Blood (1986) and South of Heaven (1988) as what they really were, albeit in repro: paintings. “I loved the music first, but then I loved the images, the upside-down crosses and so on,” says the artist, who in 2001 would paint Kirche (Church), the first of several inverted churches in reductive graphic style, dripping blue paint like blue blood. “In Poland, even if not political, you always have to position yourself in relation to the Catholic Church,” he adds, “because it’s so influential on everyday life.”

‘Visual culture’ may be a punchline for jokes about subpar university degrees, but in Sasnal’s life it has been a crucial assuaging category, the Damascene moment coming when he discovered Bauhaus, the school and aesthetic, through Bauhaus, the goth band. “Before 1989, there was a shortage of many things in Poland, but not of music – you could hear that on the radio – and that was an important moment, when I realised that there was art underneath the band I loved. Everything was equal, either music or this sophisticated art. I didn’t feel excluded.”

I loved the music first, but then I loved the images, the upside-down crosses and so on

That sense of horizontal availability was still powering Sasnal when, in 1999, finishing his studies in Kraków’s Academy of Fine Arts, he found himself “fed up with school and an ‘artistic’ way of looking at things: that the artist is a ‘creator’ in a very old-school, obsolete way. I wanted to get rid of any artistic movement. I just wanted to repaint photographs, where the only important factor is the choice. I didn’t even use colours. I just made drawings on canvas,” he says. “Of course, it’s changed now.”

Now – skimming over an interval in which Sasnal cofounded the deliberately deskilled Ładnie Group of Polish artists, worked briefly in advertising, had his comic strips published and became an artworld luminary – the photograph is effectively just the starting point for an engagement that has gotten, Sasnal says, “slower”. He’s become the kind of painter where the unpredictable needs of the painting take over. But the source material is still primarily photographic and representational, and the result has been an accumulating, off-balance oeuvre of disconnected, atmospheric fragments, extracts, edits, a constellation of black holes in which imagery can come from Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 Holocaust documentary Shoah (as in Shoah (Forest), 2003), from the annals of pop culture or from Sasnal’s own “notebook”, his camera phone.

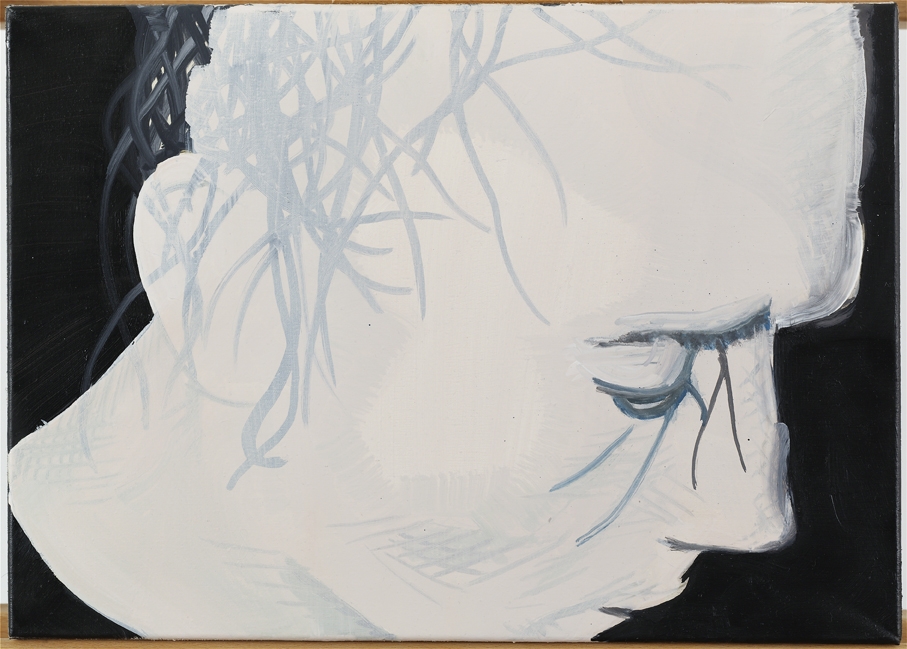

Among Sasnal’s paintings from 2006, for example, are Roy Orbison, from a publicity photo of the singer (‘the saddest person in the world, even when he smiled’, the artist wrote in his 2007 catalogue Lata Walki (Years of Struggle)); a bleached-out painting of his family (Family), where the flash went off accidentally, obliterating features; and portraits of priests accused of wrongdoing, eg, Untitled (Priest 2) and Untitled (Priest 3), which set schematic representations of their features onto loose, brushy backgrounds, faces warping and tangling. There’s a smooth, antiseptic quality about the brushstrokes in each of these that’s both fast and weighted and marks distance from ‘expressive’ painting. It’s technically superb – Sasnal says he believes in “quality and craftsmanship” – but the technique serves withholding as much as giving.

Sasnal’s imagery never tells the whole story. It’s lossy and flattened like a third generation tape recording and skids to peripheries where speech is muffled, for which reason he’s sometimes been characterised as a post-Luc Tuymans painter: see, for example, Kielce (Ski Jump, 2003), a painting of a silhouetted ski jump in a Polish town where Jews were attacked after the war. One might see this as rhetorical concerning what single images can ever really communicate, particularly about large historical events (Sasnal’s great-grandfather was in Auschwitz, and Sasnal has painted contemporary silos that recall concentration camp architecture), or as generously open-ended (Sasnal has repeatedly said that he wants the viewer to find their own readings in his work), or both. Rationales for his use of images are always implied, even if they float below the painted surface.

“Reality is a jigsaw puzzle that’s being put together, but we only see parts”

I ask Sasnal, more generally, how tenable is the hagiographic model of broken narrative that some observers have projected onto his work, in terms of growing up in a Poland that was first Communist, then post-Communist, and that is haunted by a twentieth-century history that is only partly visible. “For me,” he says, “reality is a jigsaw puzzle that’s being put together, but we only see parts – knees, say – and it’s permanently changing. I don’t know where history ends and where the present moment begins. It’s like liquid, or sometimes like mud. It doesn’t have a shape. I know this is an awkward feeling to experience sometimes, when one looks at my paintings. But basically that’s it. And maybe that’s why our films are so hard to watch, because they are broken narratives, and you lose the plot.”

Sociopolitical and locally historical concerns, accordingly, are a will-o’-the-wisp in Sasnal’s work: glimmering, there and not there. The stark recent film Huba (Parasite), for example, made using nonprofessional actors, is indivisible from an idea of ‘bare life’ that feels, firstly, tied specifically to a Polish rural context: it concerns a mother, a baby and an older man, a factory worker, sharing a raw and claustrophobic indoor life. At the same time that it reflects contemporary Poland, though, Sasnal wants the storyline to scale up to something like universality. It also scales down, being based, he says, on his and Anka’s experience of having a difficult second child: “a really harrowing experience, and I did the same for the paintings when I painted myself as a father being sucked by a parasite, by a leech or whatever”.

Getting art to operate like that, expanding and contracting depending on who’s looking, is like trapping lightning or something similar. Press too hard, know too much, and it’ll go inert and narrowly illustrative. Talking to Sasnal, you get the impression he spends as much time working on keeping his creativity alive as he does producing art, and that painting comes first. “For the sake of painting,” he says, “what’s important about being involved in making films is that it doesn’t restrain me from being in the studio every day, restrain me from thinking about painting. I don’t like to think in a dead-end way, where you’re just a painter and you always think about that. Then you start to repeat yourself; you’re just the master of yourself, and you want to be a great master. This is not my aim. I don’t want to get bored of myself, with painting. So it’s also important to be involved in film.”

“If I could say what my films and paintings have in common – then it’s anger and anxiety towards certain subjects”

An attitude to the creative process might be discerned, too, reflexively, in the art itself. An exhibition last year at Hauser & Wirth, Zürich, featured multiple images of downed motorcycle racers and also outer space (via images related to Stanisław Lem’s Solaris, 1961), linked, one would think, by the motif of the protective helmet. This all related, the press release stated, to ‘the sensation of losing control’, and if that’s something that resonates fearfully through the work, it’s also central to Sasnal’s approach, wherein it might be no bad thing.

Navigating through the imagistic thickets of his oeuvre, what feels to hold it together, time and again, is mood, as if Sasnal accepted not knowing exactly what he was doing as long as it felt right. “If I could say what my films and paintings have in common – beyond cropping and angling, because I’m also the cinematographer – then it’s anger and anxiety towards certain subjects,” he says. These are attitudes big enough to encompass worlds and histories, and in Sasnal’s art they do, from the historical cataclysm of the Holocaust to the difficulties of being a parent.

You don’t need to be an armchair psychologist to suspect that this has roots in childhood. Sasnal seems to know it too, and to be actively tapping it. The first feature he made with Anka, the monochromatic, elliptical Swiniopas (Swineherd, 2008), featuring lesbian lovers in rural Poland and an Elvis soundtrack, was loosely based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fable ‘The Swineherd’ (1842); again, the new work for Lismore relates to the author, too. “I was pretty keen on Andersen when I was a kid,” says Sasnal, “not because of the content of the stories but because of the illustrations. There’s an edition from the 1970s with three different illustrators, and they are very scary. Perverse, cruel – they don’t look like they’re for kids at all. They’ve stayed in my mind, and I repainted some of them, maybe six years ago. Then there was Swineherd. And now it’s conscious, getting back to him. But not to the stories: to the atmosphere, the mood, which is obscure, psychedelic and obsolete, and that’s what I like about it.”

Among the paintings at Hauser & Wirth last year was Untitled (J. Ch. Andersen), from 2006. In a blackout sky above a small hemisphere of planet floated a winged moon. Somewhere – perhaps in Andersen’s ‘What the Moon Saw’ (1840) – is the source material, but Sasnal’s version is both voiceless and speaking anew, conversing with crashed bikers and Stanisław Lem and coldly lunar landscapes. It speaks, in context, of the wavering ontology of painted images: the potential for an extracted scene to radiate panoplies of new significations, for a fairytale moon to turn saturnine. For us to be taken, as the Lismore Castle show’s title has it (with a nod to an Aerosmith song), to the other side.

The Andersen-related films for that exhibition, Sasnal tells me, will feature soundtracks derived from mountains of vinyl he recently picked up while spending six months in San Francisco. There’s a relation, for him, between 16mm celluloid and vinyl – this is an artist, after all, who approvingly uses the word “obsolete” in conversation and whose 2013 show at Anton Kern, New York, featured multiple paintings of analogue Kodak film canisters and logos. But what one anticipates is the happenstance conjunction of found image and found sound, fusing in an emotional sphere grander than either alone. You seem like a very instinctive artist, I suggest to Sasnal. “Yes, pretty much,” he says. “Instinctive, but not naive. When I’m working, I rarely do strict projects, because then you can’t exploit the accidents. And this is what I like about it: it’s like life. You can’t plan everything, from the very beginning to the very end.”

Wilhelm Sasnal: Take Me to the Other Side is on show at Lismore Castle Arts, County Waterford, Ireland, from 18 April to 21 September 2014

This article was first published in the April 2014 issue.