William Pope.L, Trinket, 2008 (installation view, Exhibition Hall of the Municipal Auditorium, Kansas City). Photo: E.G. Shempf. Courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

William Pope.L at Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles, through 28 June

William Pope.L has crawled the length of Manhattan’s Broadway, chained himself to a Chase bank via a length of Italian sausage while wearing a skirt made of dollar bills, and sauced and eaten The Wall Street Journal before vomiting it up again. As that work suggests, the pivotal American performance/body artist has long refused to ingest the narrative put forward by the powers that be. And in the wake of the Eric Garner case in particular – see Pope.L’s 2008 performance of self-asphyxiating via white plastic bag, which graced the cover of another art magazine recently – his MOCA show couldn’t be timelier. His largest retrospective thus far convokes several large-scale installations, including Trinket (2008/15), a 15 by 6 metre bespoke American flag blown by industrial fans and appearing, we’re told, to fray at the edges in ‘a potent metaphor for the rigours and complexities of democratic engagement and participation’.

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, scanning process for Phantom (Kingdom of all the animals and all the beasts is my name), 2015. Photo © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané at Esther Schipper, Berlin, through 30 May

Segueing into less threatening headcoverings: viewers at the New Museum Triennial can currently don an Oculus Rift headset that transports them into Brazil’s Mata Atlântica rainforest, courtesy of Daniel Steegmann Mangrané. Forests have been a locus for the Rio-based Catalan artist’s animist perspective for a while now, and the title of his show for Esther Schipper, Spiral Forest, suggests they remain so. It also signposts his yen for geometry, previously expressed via all kinds of reworked and distended grids and nature/culture interfaces, as in Phasmides (2012), his video wherein a stick insect, emblem of nonhuman agency, traverses geometric obstacles in his studio space. Despite the clear overlaps with object-oriented philosophy, Steegmann Mangrané nests more individualistic thinking about humans, nature and systems into his work and is too subtle an artist to be boxed within a trend; his wobbly, willowy, linear sculptures, in particular, engage satisfyingly without exegesis.

Liz Larner, II (inflexion), 2014. Photo: Joshua White. Courtesy the artist, Regen Projects, Los Angeles and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow

Liz Larner at Modern Institute, Glasgow, through 23 May

Wobbly linearity is one of Liz Larner’s modes too, though she’s worked in a wild variety of ways over the last few decades. She often pulls together shapes, textures and colour schemes that don’t seem like natural bedfellows, leading the brain to forge new synaptic connections to countenance them. Some of the American artist’s linear sculptures look like multicoloured scribbles in space – like a kid doodling an Anthony Caro with every colour in the pack, perhaps. Other works have been made from false eyelashes, still others from aircraft cables. Fairly consistent, nevertheless, is a gleefully associativity, Larner proceeding from formalism as if testing how many thoughts and issues it might, heretically, lead to. The field is wide open for this show, in other words – what we saw last were wall-based, glowing ceramic lozenges, thoroughly Larner in barely recalling her earlier work at all.

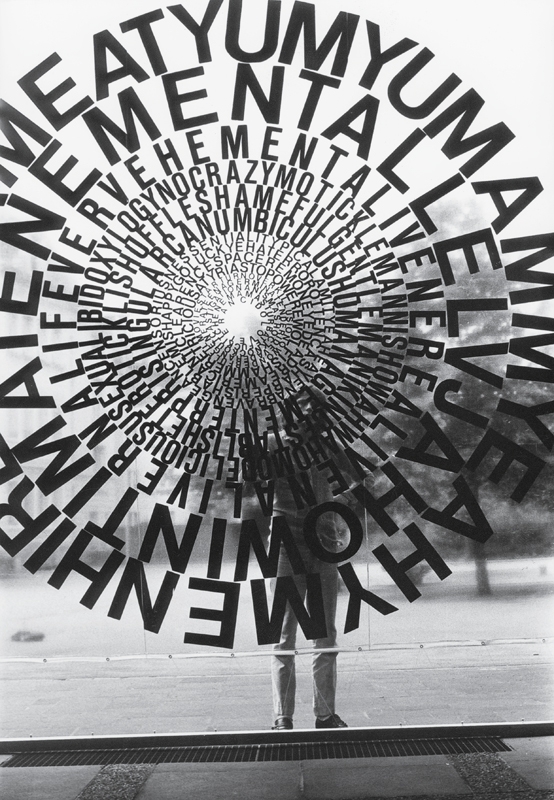

KRIWET, Text-Dia, 1970. Photo: BQ , Berlin. Courtesy Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles and BQ, Berlin

KRIWET at Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles, through 3 May

Few postwar artists have been as expansive, ambitious yet underrecognised as KRIWET, whose career in early-1960s Dusseldorf found him emerging from concrete poetry and translating cybernetics into art (on the basis, as Cherry and Martin notes, that ‘art is information and information is art’), with a particular focus on the effects of overstimulation. It’s taken until recently for the world to catch up with him. For the German artist, reality is a continuous moving field of information, which is perhaps why his work has ranged widely around that field, from club design to radio texts and films about the first Apollo landings, happenings, ‘poem paintings’ and books without capitalisation or punctuation. In his first West Coast show, the gallery has the unenviable task of parsing that fizzing sprawl, though the chaos – the traversal of fragments – is its own painful-pleasurable reward, a percolating picture of the overheated informational world.

Frances Stark, Untitled, 2014. Photo: Marcus Leith. Courtesy Greengrassi, London

Frances Stark at Greengrassi, London, 30 April – 20 June

Some artists, of course, see technology less as a stressor than an opportunity – certainly that’s the case with Frances Stark, whose modern classic My Best Thing (2011), a feature-length video, found her probing the world of online flirting via an extended, sometimes filthy, sometimes tender conversation with an Italian stranger, rendered as a video using computer-generated speech and comically basic avatar-modelling. Self-consciousness is the LA artist’s main material, which she’s continuing to explore through her primary medium, drawing and collage, sometimes edging into abstract poetics: when people talk about the recent importation of the literary, the overflowing textual, into contemporary art, Stark was there very early and is likely to still be there in this, her fifth show with Greengrassi.

Richard Prince, Untitled (portrait), 2014. ©Richard Prince. Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe

Richard Prince at Blum & Poe, Tokyo, through 30 May

Richard Prince’s Instagram-themed artworks, a Jerry Saltz review suggested recently, are ‘genius trolling’, irritating some by appearing utterly easy, sexist, celebratory of banality and tossed-off: big, low-res, pixelated prints enlarging the source and revealing its technical shortcomings, these works gave Peter Schjeldahl, as he wrote, something resembling ‘a wish to be dead’. Their irritant value is high, certainly. As is the unassuming complexity of the comments, which Prince – playing some sort of ambiguous hipster dirty old man – both takes part in and reproduces. As, too, is the variety of the source feeds, which ranges from those of selfie-posting teen girls to those of Prince’s artist friends. Not long ago he was suspended from Instagram for posting his notorious 1983 image of a nude Brooke Shields, Spiritual America. More recently, he got in trouble again when Gagosian exhibited one of his Instagram pictures, featuring an image – this one of a Rastafarian, in a strange echo of his feud with photographer Patrick Cariou – uploaded without accreditation/permission, and the photographer in question sent a cease-and-desist. Let’s see if this show can somehow go off without a hitch.

Peter Land, Boy & Girl, 2012. Photo: Erich Malther. Courtesy Galleri Nicolai Wallner

Peter Land at Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, 24 April – 6 June

Historically, many of Peter Land’s artworks haven’t been complete without a hitch. Ahead of the curve of art-as-slapstick (though a little behind that of Bas Jan Ader), the Danish artist has, in his films from the mid-1990s onwards, fallen down a flight of stairs and off a stepladder, played the cello naked, climbed into a boat and shot a hole in it and sat there sinking, filmed and drawn himself drunk, and offered whiskey to gallery visitors. More recently, he’s focused on drawings and paintings that suggest creepy children’s book illustration, and strange realist sculptures featuring, say, people in bed with enormously distended limbs trailing on the floor. Land, who’s had an up-and-down career, seems genuinely touched by mayhem and, one suspects, gives about as much of a fuck as Prince does. Even if we did know what he was going to show at Nicolai Wallner, we’d rather not spoil the surprise.

Cathy Wilkes, Untitled, 2011. Photo: Tom Little. Courtesy the artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow, The Henry L. Hillman Fund, Carnegie Museum of Art

Cathy Wilkes at Tate Liverpool, through 31 May

One might not necessarily think of Cathy Wilkes as a neo-surrealist, but that’s seemingly how Tate Liverpool is presenting her, exhibiting a decade’s worth of the Irish artist’s work alongside shows by Leonora Carrington and György Kepes in a season entitled Surreal Landscapes. It makes some sense. Wilkes’s tableaux of mannequins and sketchy environments, which she has said are populated by both the living and the dead, have the mixture of specificity and incomprehensibility that characterises first-wave Surrealism. Bits of biblical narrative, for example, intertwine with workaday items such as baby buggies and apricot jam, toy rabbits and electric kettles, while Wilkes’s installations in turn intersect with her abstract paintings. Her art sits, in fact, strangely close to the edge: if she didn’t have a stated interest in intentionality per se, in refusing responsibility for readings (and, of course, if she didn’t have an art-school background), her work could fit into the canon of outsider art. As it is, she’s way inside; but nevertheless the work retains its power to perplex.

Athanasios Argianas, Song Machine (A Chair For Your Memory) series, (vs 3 4 and 5), 2015 (installation view). Photo: Nick Koustenis. Courtesy On Stellar Rays and the artist

Athanasios Argianas at On Stellar Rays, New York, 2 April – 3 May

Athanasios Argianas started out with a recognisable format, one that he sometimes still uses, while evolving it: his Song Machines, elegantly curving linear sculptures, now strung with thin lengths of brass, engraved with lyrical phrases. These suggest analogues for music that unfolds in space, leaving the viewer to move along the object, read and, perhaps, inwardly hear something. The Greek artist, who lives between London and Athens, has long made work that revolves around types of translation and situational adaptation (the latter, of course, particularly an issue in his unsettled homeland), perched midway between sound and space, language and object. Here, alongside several linear sculptures, poetic lines concerning colour and bodies will be etched onto finger cymbals. If neither of the latter will be physically present, they become present in thought: the realm of sculpture, within Argianas’s pointedly open-ended programme, seemingly extends inside one’s mind.

Marina Abramović, Virgin Warrior 1, Pietà (with Jan Fabre), 2005. Courtesy & collection Arsfutura-Serge Le Borgne, Paris. © the artist / VEGAP, Madrid

Jan Fabre at MuKHA, Antwerp, 24 April – 26 July

We began with performance and end with it – specifically that of Jan Fabre, who may not have crawled the length of Broadway but did, for three days in 1980, have himself locked in a room, in which the now-veteran Belgian artist spent his time drawing on things with Bic pens. Indeed, deep-blue Bic hatching is one of his artistic signatures, alongside his fascination with beetles, which he has used to encrust various surfaces. (And one can discern parallels between his relentless line-making and his application of countless bugs’ wings.) He’s made drawings with his own blood, produced 24-hour endurance theatre events and claims everything he does is related somehow to metamorphosis and the human body – even, one would guess, the scarabs, which have shown great capacity for adaptation over millennia. At MuKHA, expect ‘a veritable sea’ of glass-topped tables to feature a huge diversity of mementoes from his performances between 1976 and 2013, and expect it to look gratifyingly off-beam, perhaps not surprisingly given Fabre’s asserting, a few years ago, that ‘an artist should not think about things that are fashionable or actual at the moment. He should simply create.’ Word.

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue of ArtReview.