Art criticism has no set definition and no consensus as to what it is (as art historian James Elkins has gleefully pointed out many times). If we don’t know what it is, does it even exist? A few years ago, the UK Home Office refused my application for residency as an art critic, claiming that art criticism wasn’t writing but a form of advertising. They had a point: the critic’s relationship to the exhibition and the art object is, at least in part, to convey, to involve and to – at least conceptually, but sometimes literally – sell the art. But it’s also, as this collection of short essays, poems, reviews and lists by Maria Fusco proclaims, a lot grittier, muckier and more fun than that. At the centre of the book is a contention of the risky paradox of writing about art, where the writing fixes the absent artwork into a specific meaning. It’s the ‘about’, Fusco contends, that’s the problem. ‘Art writing’, as she refers to it (within which criticism is just one facet), should remain restlessly, endlessly prepositional: not just ‘about’, but also ‘in’, ‘with’, ‘of’, ‘on’ or even ‘off’.

As a slim selection of Fusco’s output from 2005 to 2013 – including texts for exhibitions, presentations for conferences on criticism and pieces for art publications like Art Monthly, Dot Dot Dot and Untitled – the book is unashamedly meta. It comes with its own manifesto, via ‘11 Statements Around Art Writing’, a set of dry dictums cowritten with her coconspirators Yve Lomax, Michael Newman and Julian Rifkin at the now-gone MFA Art Writing programme at Goldsmiths, of which Fusco was founding director (including, ‘6. Art writing is in the situation of the fulcrum’, by which I imagine writing as a crowbar, to be used to pry open, or smash); as well as Fusco’s reading list of comics and postmodern fiction, reprinted from Frieze’s ‘Ideal Syllabus’ series. In between texts about art writing (and more than a few enjoyably enigmatic aphorisms, such as ‘constriction and consistency make a pair of muscular thighs: our heads are happy clenched between these very thighs’), a few short pieces illustrate the ‘in’, ‘of’ and ‘off’ approach, with impressionistic texts that write from the perspective of, say, a sewing machine, or actor Donald Sutherland’s face. Continuing the inner logic of the artwork and seeing where it might go, it’s an approach that’s at times unexpectedly intimate, at others more whimsical, though collected here it also becomes apparent that a preposition indicates placement; removed from the contexts that produced, elicited, inspired or birthed them, some texts end up feeling enigmatic, or a little lost.

A sense of absence, of things referring to other things, permeates the book. Fusco writes, engagingly, about the process of creating a script for artist Ursula Mayer, based on an Ayn Rand play (but doesn’t reproduce the script); a short review of a performance at the Barbican by German composer Heiner Goebbels seems included here precisely because the event was based on transposing a series of texts by T.S. Eliot, Kafka and Beckett into music. But most prominent is the elusiveness of the art writing itself, talked about as a perpetually arriving possibility. ‘What I’m interested in is what art writing might be, rather than what it actually is’, she states in ‘Say Who I Am, or A Broad Private Wink’, calling for writing ‘enacting critical judgements through question after question rather than answer after answer’. What it is, then, is endlessly deferred, and Fusco seems happy to stand on the threshold and gesture towards this wonderful world of pure imagination.

To write not-about art, then, seems to be to deny explanation, to avoid the pretence of objectivity, to involve by immersion. Fusco’s art writing is more akin to the role of the artist, another link continuing a chain of creation. But the activity of criticism Fusco proposes isn’t just passing the buck, it’s more an initial attempt to locate criticality in creativity. This book is a guide to a few approaches, a toolbox in the punk spirit of ‘this is a chord, this is another, now go start a band’. In bouncing around these translations and transmutations in writing as, of and around things, what arises at points, interestingly and unexpectedly, is a confusion of subjectivities, a productive smudging of the ‘I’ that is assumed to be the Receiver, Interpreter and Endpoint of art. What does such writing tell us about art? It tells us to dig deeper; to bring your own goddamn shovel, and then to be the shovel, and to be the hole.

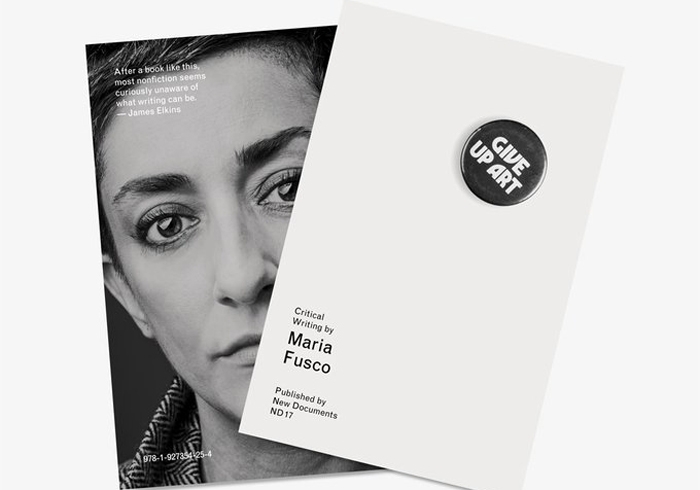

Give Up Art by Maria Fusco, published by New Documents, €28 / £22 (softcover)

From the April 2018 issue of ArtReview