“Why won’t you admit that we’re standing in a cruise ship?”, says my wife. We are at Magali Reus’s exhibition As mist, description, held at South London Gallery in the spring of 2018, and we have reached an impasse. She is also indignant that the gallery has failed to mention this crucial information in the literature. In the assemblages around the room I see the ghosts of many familiar things. Gas meters, the interior design common to corporate lobbies, flower pots and vases, plastic toy model kits with snap-off parts. What I do not see is a cruise ship.

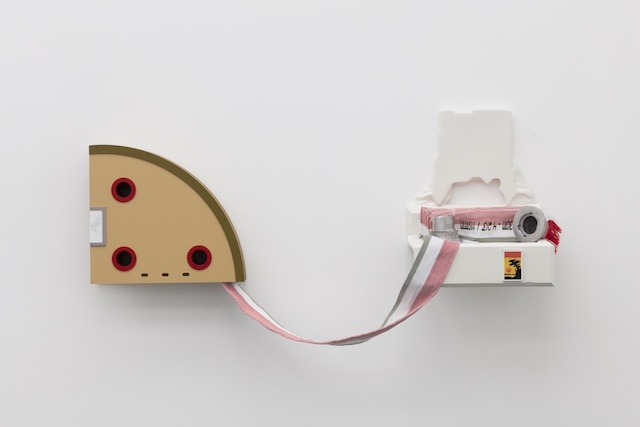

“You can at least agree that this is an onboard firehose,” she says, directing my attention to a length of red, white and green striped fabric coming out of a dispenser on the wall. The end of the fabric is carefully folded on a separate shelf, wedged in position by two pieces of serious-looking metal hardware – the sort of parts you don’t want coming off in your hand when attempting DIY plumbing. I inspect the objects before me, and find their flawless surfaces, and the pernickety, demonstrative manner of their display, unnervingly cool, as if they have travelled from design software to factory to gallery without coming in to contact with anything warmblooded. “More like the reusable hand towels you get in public loos,” I counter, less from a place of conviction than from a reluctance to admit defeat. She sighs, looks at me with a one-two punch of pity and incredulity, and delivers the final blow. “It’s just so… obvious.”

By the time we leave the exhibition I’m facing an unattractive realisation: my wife and I have become the art-viewing equivalent of provincial tourists

By the time we leave the exhibition I’m facing an unattractive realisation: my wife and I have become the art-viewing equivalent of provincial tourists. We are now the kinds of people who will go to any length to maintain their delusion of authority, insisting that the street on which they are lost looks just like their home town, and squabbling over whether the waiter with whom they’re failing to communicate looks more like uncle John or cousin Rob. Because, in the Hand Towel vs Firehose debate, what we were both unwilling to admit was that an unfamiliar object existed beyond our capacity to comprehensively account for it. (That evening I google reviews of the exhibition, and find it confidently summarised as the interior of a whale, and a London Routemaster bus. Apophenia, it seems, is a common condition.)

Nobody wants to be that tourist. As mist, description had made me aware that I’d been harbouring an overfamiliarity with the material world. During the coming weeks, in an attempt to rectify the problem, I try to embrace a state of not knowing, turning to the philosopher Graham Harman as an aid. In his 2010 book Towards Speculative Realism, Harman argues against anthropocentrism, the tendency to perceive phenomena primarily based upon their value to humans. Instead, he makes the case for considering objects as autonomous entities, beyond the limited scope of their role as a tool or possession. ‘To create something’, he says, ‘does not mean to see through to its depths.’ Harman’s point appears to be simple: just as a child must learn that the world does not disappear when they close their eyes, we must also learn that the products of human endeavour move beyond our control and knowledge. Applying this theory to everyday life, however, is considerably more difficult. Opening the fridge one morning to get the milk for my cereal, the appliance I once considered primarily as ‘mine’ is instead an assembly of rubber seals, plastic casings, welded and coated steel, and other alien parts, each the product of different economic, material and labour ecosystems, each with a language, history and lifespan profoundly other to my own. I close the door on this chasm of estrangement, and opt for a banana instead.

Opening the fridge one morning to get the milk for my cereal, the appliance I once considered primarily as ‘mine’ is instead an assembly of rubber seals, plastic casings and other alien parts…each with a language, history and lifespan profoundly other to my own

To the question ‘What kind of art do you like?’ I am yet to reply, ‘Anything that makes me feel fundamentally alienated from the world in which I live every time I open the fridge’. This, however, is precisely what I admire about Reus’s work. She keeps the chasm open. I consider this to be a type of realism: an attempt to speak of the material world, not as we would prefer to see it, but in its own tongue. Today this is no easy task. Little wonder there has been a resurgent interest in handmade arts and craft histories, for nostalgic practices that affirm the primacy of the human touch. The industrial, global and often unknowable life of today’s object offers little in the way of succour, to artist or to viewer.

Exemplary of this realism is Leaves, a series of sculptures for which Reus won the Prix de Rome in 2015. At first glance the objects appear to be oversize padlocks, with metal shanks protruding from the top, and parts of their internal mechanisms exposed. Yet the shanks are incomplete, and in a number of the works, the body of the object is produced from multiple layers, making it impossible to consider the lock as a single, unitary entity, or even as a lock at all. Leaves sets in motion a type of semantic entropy: just as repeating a word over and again distances it from its referent, each iteration of the ‘lock’ further erodes my ability to quantify it. The effect is rather like misplacing a familiar phrase, only to discover that you’ve lost an entire language.

Part of what makes viewing Reus’s sculptures so disorientating is that despite their alienness, they also appear to be entirely plausible. Surfaces are cast, milled and powder-coated, colours unremarkably schematised, each assemblage evidently the result of purposeful design processes. Their familiar, professional bearing is such that my inability to define them is matched by a persistent sensation that at any moment I will be able to. When Leaves was installed at Hepworth Wakefield in 2015, as part of Reus’s exhibition Particle Of Inch, it was shown alongside In Place Of (2015). A series of floor-based sculptures, In Place Of demonstrates Reus’s unsettling ability to stretch the possibilities of classification in multiple and contradictory directions at once. Each work is a variation on a theme: a low, fastidiously well turned-out structure that could convincingly pass as a maquette of a modernist villa or car park, a plinth, a coffee table or even a giant circuitboard, and upon which a variety of miscellaneous and equally fugitive items are displayed.

To view In Place Of is to succumb to an anxiety of taxonomy: the more credible explanations that emerge, the less I feel capable of resolving the nature of the object in question. This combination of uncertainty and self-possession is what gives Reus’s work its distinct psychological profile. It also puts me in mind of Julia Kristeva’s theory of the stranger. The Bulgarian-French writer believes that we are all, to varying degrees, strangers to each other and to ourselves, and that we cover over our inner turmoil by creating an outer shell, learning to ‘settle within the self with a smooth, opaque certainty – an oyster shut under the flooding tide, or the expressionless joy of warm stones’. Just as strangers go unnoticed when dressed in familiar clothes, in Reus’s sculptures, ontological disquiet is presented with the blank confidence of commercial finishing techniques. A portrait of the object for the present day.

Work by Magali Reus appears in The Hepworth Prize for Sculpture, at Hepworth Wakefield, through 20 January

From the December 2018 issue of ArtReview