Christian Boltanski at Centre Pompidou, Paris, through 16 March

It’s a decade now since Christian Boltanski filled Paris’s vast Grand Palais with Personnes (2010), piles of used clothing and the sound of human heartbeats, the latter part of an audio archive that the French artist is compiling to eventually have stored on a distant Japanese island. And it’s 35 years since the mortality-and-memory obsessed Boltanski had his first show at the Centre Pompidou. During that time, as this 50-work show will illuminate, he’s moved from plangent memorials using manipulated, individually lit photographs – particularly Jewish children during the 1930s – to become a maestro of largescale installations both unsettling and absurd. He’s also become his own archivist, having sold Tasmanian collector David Walsh the rights, in 2009, to a 24-hour live feed of his studio until the artist’s death. Boltanski’s controlling instincts extend to this self-designed retrospective, which the institution calls a ‘vast journey into the heart of his work’ and which ticks off a myriad of emblematic pieces, from the desolate memorabilia of Vitrine de référence (1971) to the three-screen Misterios (2017), documenting an installation of three giant trumpets in Patagonia that use the wind to mimic whale song. Why whales? Boltanski reckons these ancient, enduring creatures might have the answers to life’s largest questions; humans certainly don’t.

Judy Chicago at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, through 19 April

At the age of eighty, Judy Chicago is finally receiving an institutional survey in the UK. To be fair, the artist who took a new surname from her hometown has never been forgotten, thanks to her immortal The Dinner Party (1979). This hugely significant feminist artwork serves – excuse the pun – as a history of significant women in civilisation via 39 place settings on embroidered runners, memorialising figures from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Georgia O’Keeffe and, having toured extensively, has apparently been seen by some 15 million people. The rest of Chicago’s oeuvre, though, is rather less known. Baltic’s show traces its 50-year span, from her feminist Land art during the late 60s and early performative works in the desert – Chicago became a teacher at CalArts during the early 70s – to The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2013–16), an exploration of mortality expressed primarily via some 40 porcelain and glass works corresponding to the five stages of grief.

Making Knowing: Craft in Art 1950–2019 at Whitney Museum, New York, through January 2021

Recent decades have seen craft aesthetics like Chicago’s appearing to swing repeatedly back into fashion in reaction to hands-off, fabricated artmaking, but that’s the short version of a longer story. The Whitney’s Making Knowing: Craft in Art 1950–2019 argues for a seven-decade continuum of artists knitting, potting, beading, glassmaking etc, with a myriad of rationales, not least the desire to undercut machismo, reclaim the vernacular and mess with perceived standards concerning what constitutes art. This rubric, articulated through some 80 works by 60 artists, makes for some surprising bedfellows – the bed is covered, obviously, with a handmade quilt – from Eva Hesse to Mike Kelley, Liza Lou to Robert Rauschenberg. It also recasts craft as a form of subversion, linked to queer aesthetics and feminism but also abstraction and popular culture. Meanwhile, and as the title’s dates suggest, in order to avoid presenting a history lesson but rather offer up a living tradition, the show is craftily augmented by new commissions from, inter alia, Shan Goshorn, Simone Leigh and Erin Jane Nelson.

Cadavre exquis at Phi centre, Montreal, through 19 January

At the other end of the spectrum, meanwhile, there’s virtual reality, still knocking on the artworld’s door. As showcased in Cadavre exquis, a range of artists in recent years have taken up the still-nascent technology, from figures you might expect (Olafur Eliasson) to those you mightn’t (hello, Antony Gormley), much of it boosted by the Daniel Birnbaum-helmed startup Acute Art. To the aforementioned artists’ names, this show adds figures including Paul McCarthy, Laurie Anderson, Marina Abramovic and Koo Jeong A, and a curatorial conceit that links high – and low – tech. The choose-your-own-adventure aspect of VR, it’s argued, is similar to the surrealist game of the exquisite corpse, in which multiple makers are involved in the creation of something – there, on paper, here with silly-looking goggles on. Roll up, anyway, and experience soaring sea levels with Abramovic’s ‘troubling yet poetic’ Rising (2018), immerse yourself in a bad-trip Western via McCarthy’s Coach Stage Stage Coach (2017) and travel into outer space with Gormley, if that’s your thing. (Meanwhile, I’m off to get a job doing voiceovers for film trailers.)

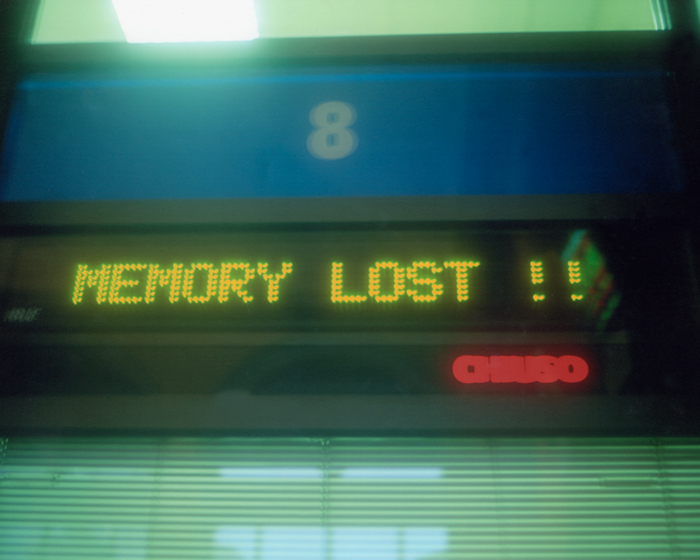

Nan Goldin at Marian Goodman, London, through 11 January

Of late, Nan Goldin’s abilities as an activist against opioid-mongers the Sackler family – and the art institutions that facilitate their artwashing – has threatened to eclipse her artistic career. In the midst of her campaigning, though, she joined Marian Goodman Gallery, and her first show there, Sirens, is a reminder of Goldin’s greatness behind the camera. But it also serves as an extension of her cause. Alongside a mix of historical works including a reedit of her superb The Other Side (1994–2019), the exhibition showcases her new digital slideshow, Memory Lost (2019), ‘recounting a life lived through the lens of drug addiction’, and a seeming counterpart to her legendary 1985 slideshow The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Which would seem like plenty, but the show also includes a new, three-screen video installation, Salome (2019), adopting the Biblical story to emphasise wider themes of seduction, temptation and revenge, and a cooldown selection of sky and landscape photos, a counterpoint to the ravages documented elsewhere.

Bamako Encounters at various venues, Bamako, through 31 January

In 1977 the jazz musicians Abdullah Ibrahim and Max Roach made a record called Streams of Consciousness, remarking as they did so that they hoped one day it’d lend its name to a photography biennale in Mali. That moment has now come: the 12th edition of Bamako Encounters, under artistic director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung and a team of curators, uses the record’s title as a jumping-off point to consider lensbased media as, indeed, a stream of consciousness, any photograph being merely a momentary outcropping of a continuous inner voicing. Beyond that, the idea of a ‘stream’ is also applied here to Africa, its diasporas and its cultures: ‘the flux of ideas, peoples, cultures that flow across and along with rivers like the Niger, Congo, Nile or Mississippi’. Expect articulations on these themes from some 85 photographic artists from the African artworld, including Bouchra Khalili, Guy Woueté, Badr El Hammami, Theaster Gates and The Otolith Group.

Ernesto Neto at MALBA, Buenos Aires, through 16 February

Limber up. An Ernesto Neto artwork generally asks for your participation – he’s one of the major proponents, even anticipators, of relational aesthetics, though his work might also recall the crash-pad vibes of fellow Brazilian Hélio Oiticica and neoconcrete art in general – and this retrospective, Soplo, is 60 works strong. Neto’s art often invites you to climb into tunnels or recline in hammocklike crocheted shapes, touch stocking fabric and whiff the spices he inserts into his art. The institution asserts that this is not just chillout art: Neto, they claim, is interested in the relationship between the individual and the collective, as modelled by the groups of viewers engaging with his art. This establishes a space, potentially at least, for ritual, and Neto wants to stress the spiritual aspects of bodily awareness. Related to that, one room in the show showcases Neto’s recent work with the political and spiritual leaders of the Huni Kuin peoples, indigenous Brazilians and Peruvians who live on the banks of the countries’ rivers.

Isa Genzken at Peder Lund, Oslo, through 15 February

Has Isa Genzken ever had an exhibition in Norway, you ask? Well, last month I’d have said no, but now… anyway, enough blather, the storied German artist is descending on Oslo with, apparently, work from her major phases since the 1980s, including her half-architecture, half-abstraction ‘New Buildings’ maquettes, Nefertiti-referencing assemblages, and – of course – paint-doused mannequins that eerily undercut consumerist urges. As ever with Genzken, the structures of advanced capitalism provide a jumping-off point for art that at once feels critical but also reroutes the energies of what it analyses. That said, you never know with her whether you’re going to get a lively display or an oddly static one: fingers crossed that this show, which features ‘five major sculptural works, as well as two outstanding wall works’, is one of the former.

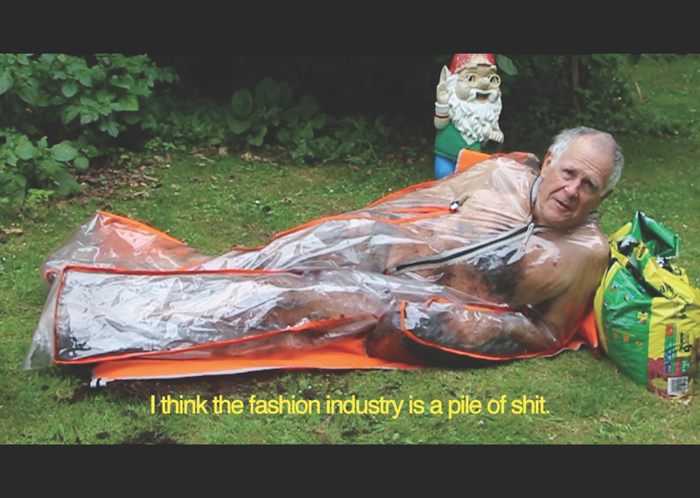

Bloomberg New Contemporaries at South London Gallery, 5 December – 24 February

But enough artists with decades of activity behind them. How about some with, like, hours of activity behind them instead. Every year, Bloomberg New Contemporaries filters the best recent UK fine art graduates through the subjective scrim of guest selectors, this time Ben Rivers, Rana Begum and Sonia Boyce. And, as you might expect, a show that takes the measure of young British art in the twenty-first century is less defined by a guiding style than heterogeneity: the inclusions here range from Paul Jex’s pointed deconstructions of the language of The Guardian’s artist obituaries – noting how many times Anthony Caro’s name was mentioned in his partner’s obit – to Jan Agha’s paintings of angry-faced cartoonish figures, to Annie Mackinnon’s video in which a naked middleaged man in a plastic bag with compost in it, an outfit seemingly responding in some way to climate change, opines to camera that he ‘think[s] the fashion industry is a pile of shit’.

Ren Hang at C/O Berlin, 7 December – 29 February

Ren Hang didn’t live to see his 30th year – depressive, he died by suicide in 2017 – but by the time of his death he’d already achieved plenty. Within the censorious context of contemporary China, Ren’s photography gravitated to gay erotica, which won him the support of fellow iconoclast Ai Weiwei (who included him in the memorably titled 2013 show Fuck Off 2 The Sequel). His work is characterised by beauty and abstraction, bending the bodies of his sitters into unlikely, near-unintelligible shapes in a manner recalling Edward Weston, and mixing iconographic references to Shakespeare’s Ophelia, Leda and the Swan, etc. Ren mixed his artmaking with editorial spreads for high fashion – not least Gucci – and managed to straddle the two by, as Ai pointed out, vouchsafing emptiness and superficiality. At C/O Berlin, a comprehensive retrospective featuring some 150 works explores his bittersweet legacy, its title aptly a tender signoff: Love, Ren Hang.

From the December 2019 issue of ArtReview