The title of the latest edition of Prospect New Orleans, the citywide triennial founded in 2008 in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, is The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp. Yes, that’s right, The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp. Seventeen venues house the exhibition’s 73 participating artists, duos and collectives, though the city’s three art museums hold a massive majority share. Apparently based on a poetic quote from musician and educator Archie Shepp about the origins of jazz, the exhibition’s didactics tag on enough generic references to Buddhism, Hinduism and other ideas about art and rebirth to make one wonder whether the artistic director, Trevor Schoonmaker, and his team would have offered such a tepid metaphor about renewal in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. And if not then, why exactly do audiences deserve it now?

However, Prospect.4 does seem to predict the current mainstream debate surrounding public monuments. Indeed, in that regard it appears to have followed the lead of New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu, who spearheaded the removal of several confederate statues in May 2017. “The South lost,” he declared several times. “Its cause was immoral.” Redressing these art-historical legacies, certain works can be plucked out as exemplary. Hank Willis Thomas’s History of the Conquest (2017), a statue of a young black girl riding a close-to-two-metre-tall snail, appears to resemble some queer local folklore; and Rebecca Belmore’s Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother (1991), a massive megaphone handmade from wood and hide, prompts connections between indigenous tradition, monumentality and protest. It is worth consuming a large portion of an afternoon to chase the many colourful flags Odili Donald Odita designed to commemorate important sites in local black history for Indivisible and Invincible: Monuments to Black Liberation and Celebration in the City of New Orleans (2017). Still, the exhibition previously known to put art at the service of the city’s demands cordons this conversation off to institutional spaces or depends too heavily on international biennial stalwarts like Larry Achiampong, Kader Attia, Paulo Nazareth and Yoko Ono. Is Runo Lagomarsino’s eponymous riverside mural If You Don’t Know What the South Is, It’s Simply Because You’re from the North (2017) really so provocative?

At the New Orleans Jazz Museum you may also experience Mardi Gras Indian costumes from Darryl Montana, a centuries-old tradition that melds black and Native American traditions in the postcolonial South; you’ll also discover collages by famed jazz pioneer Louis Armstrong, including one dedicated to his devotion for a certain brand of natural laxative. Biennials are great at cherry-picking, though Prospect.4 lacks the self-awareness that allowed previous iterations to really pinpoint their stakes. ‘I am a tourism promoter,’ the curator of the first Prospect, Dan Cameron, was quoted as saying in The New Yorker. I would appreciate it if Schoonmaker, and biennial leadership, would explain why they felt it was appropriate to install Genevieve Gaignard’s Grassroots (2017) at the Ace Hotel. An exhibition sponsor, the boutique hotel chain is known for a bespoke comfort – the eye they train on every aesthetic decision is guided by an effort to pass as local. Though Gaignard’s installation uses church pews, vintage mirrors and patterned wallpaper, things you’d already expect to find at an Ace Hotel, it is disturbing just how easily a series of slave ship manifests could decorate the lobby, too.

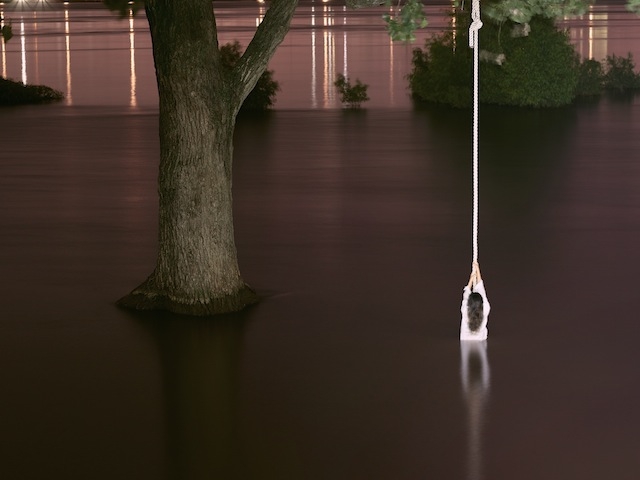

Prospect.4 is an exhibition in spite of the curator. Some of the most beguiling work was captivated by the flood cycles of the Mississippi Delta itself. At UNO – St. Claude Gallery, photographer Jeff Whetstone’s series Batture Ritual (2017) is named after the in-between zone at river’s edge. The images show people, fish and tankers as they make their way up the Mississippi, locals taking evening recreation, others bathing; many of the images were shot at dusk and dawn, though the video of the same name shows the liminal area at all times of day. One image depicts a dead catfish that gleams all over with jewellike flies: the lucid light invokes Dutch still-life paintings from a bygone age of prosperity. The batture, which succumbs to seasonal flooding, is a reminder of the flood risk that pervades New Orleans, a city positioned below sea level; according to NPR, though, New Orleans successfully lobbied the federal government to remove emergency flood ratings that had prevented real-estate investment in areas that had been most affected by Katrina. In Monique Verdin’s photographs, the batture is positioned as a site of disappearance: her show at the Historic New Orleans Collection documents the United Houma Nation, a tribe located in southern Louisiana, and of which Verdin is a member. Mark Dion deliberately positioned Field Station for the Melancholy Biologist (2017) within the flood zone so that it will be destroyed when the river rises in winter. For now, the clapboard shed houses a tiny field-lab full of scientific instruments and animal specimens, but it will be funny when the water releases everything from its current state of captivity, including the contents of a cabinet Dion filled entirely with aspirin.

The total lack of compunction on the part of a single rogue dancer (whoever it was in that Lycra bodysuit, they were feeling themselves) provided many of us with the strongest memory from the Swamp Galaxy Gala, an inaugural event for Prospect.4. Though the crowd’s phone cameras were trained elsewhere, it was actually the city’s mayor who would unwittingly set out the stakes of this edition of the triennial. Earlier editions of Prospect made urgent the larger concerns of the city, and artists notably tailored their contributions to also include financial support and other community-based resources; that biennials are strategic assets (and Prospect’s website states this very clearly) is a trap that curators of this edition succumbed to, clearly unwilling to needle the rampant real-estate market and a growing housing crisis. Who knows what went through Mayor Landrieu’s mind as he delivered his last Prospect commencement. The opening of the exhibition coincided with the mayoral election, and the city would determine his successor; local newspapers displayed pull quotes from leading candidates declaring their intention to stand up to developers. TV appearances, TED Talks, and participation at the Aspen Institute incubator have by now made Landrieu a pundit, and a New York Times editorial even named him a potential democratic presidential nominee. The greatest innovation is happening at the local level, Landrieu says, often to preface his vision of bipartisan compromise during any of his national speaking gigs. Tonight, though, he was far less convincing. “We’ve built schools, hospitals, parks,” he outlined towards the end of his gala speech, “to which Prospect has added considerable value.” I bet it did.

Various venues, New Orleans, 18 November – 25 February

From the January & February 2018 issue of ArtReview