Here’s what’s going down in Coconino County: Ignatz Mouse is pursuing a vendetta against Krazy Kat, which he satisfies by launching bricks at his head. Order is fitfully maintained by Officer Bull Pupp, who loves Krazy, who loves Ignatz, who loves bricks. Hundreds of variations on this scenario, played out in George Herriman’s syndicated comic strip from 1913 to 1944, form one of the great bodies of work in popular American art.

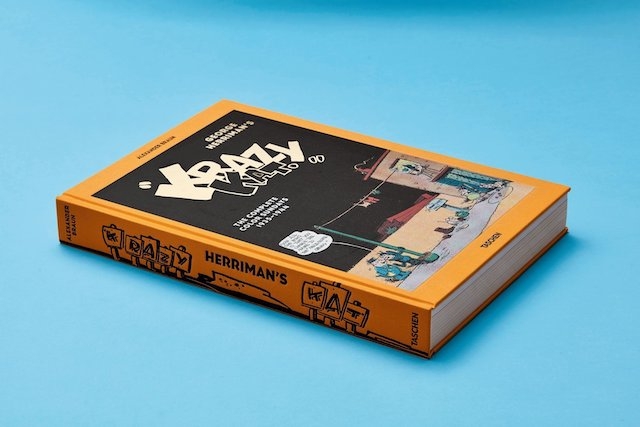

Taschen’s colossal and highly covetable anthology reproduces the colour strips made in the final ten years of Herriman’s life. These blown-up panels make it easier to appreciate the wit concealed in their details, the energy of the artist’s line and his surrealist disregard for continuity: in the course of a 30-second conversation, Ignatz and Krazy might walk from a barren desert through a verdant park and onto a footlit stage. These dreamlike incongruities mean each strip resembles a collage, allowing Herriman to treat individual panels as discrete compositions while experimenting with the overall page design (the conventional comic-strip grid fractured into a constructivist jigsaw or mussed into a scrapbook jumble).

If Herriman’s popularity was built on the charm of his characters, then his artistic reputation relies on this formal and intellectual playfulness. In 1937, sneaky Ignatz reaches out from what appears to be a painted portrait to fire a painted brick at Krazy (Pupp retaliates by painting black bars over the portrait, imprisoning the real and represented mouse). The treachery of images is a recurring theme, with a 1917 strip (reprinted here within an illuminating introduction by Alexander Braun) revolving around ‘oon “peep”… meaning a “pipe” and not a “look”’. Krazy, who is not a cat, and Ignatz, who is not a mouse, smoke the not-a-pipe, and a stoned peace breaks out beneath a cartwheeling sun cross.

These and other nods to Native American mythology jostle with Krazy’s creole and Chinese-heritage platypuses in this multicultural Arizona, and Braun highlights Herriman’s status as a white-passing descendent of Haitian ‘free people of colour’ before suggesting that Krazy started life as an allegory for minority ethnic experience. He cautions against reading the oeuvre exclusively through the prism of colour –¬it doesn’t stand up beyond a wilfully selective reading – but this topsy-turvy community, in which a cat loves a mouse from whom he is protected by a dog, is an apologue for a functioning (which is not to say utopian) American society. Because there is no animosity here. Our hero Krazy receives each brick-blow from Ignatz as a ‘missil of affection’ from his ‘l’il ainjil’, a cluster of hearts bursting from his head; the mischievous Ignatz, meanwhile, is lost without Krazy to play with and never happier than when dozing in Pupp’s adobe jailhouse. The balance of this community is maintained by each part’s fidelity to their own selves. Ignatz must act up; Pupp must order; Krazy must love.

This selection straddles a decade shaped by economic collapse and the rise of fascism, and another marked by resistance and recovery. At the end of our own dishonest decade, it’s worth reflecting on the fact that Herriman’s paean to play and empathy was read by millions of Americans on lazy Sunday afternoons. In late August 1939, Officer Pupp is moved by thoughts of Ignatz’s happy family to reflect that ‘the world walks in beauty’, quoting a Navajo prayer just a few days before W.H. Auden will write in 1 September 1939 that ‘we must love one another or die’. Auden later explained that ‘there must always be two kinds of art: escape-art, for man needs escape as he needs food and deep sleep, and parable-art, that art which shall teach man to unlearn hatred and learn love’. Krazy Kat is both.

George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat”. The Complete Color Sundays 1935–1944, by Alexander Braun, Taschen, £150 (hardcover)

From the January & February 2020 issue of ArtReview