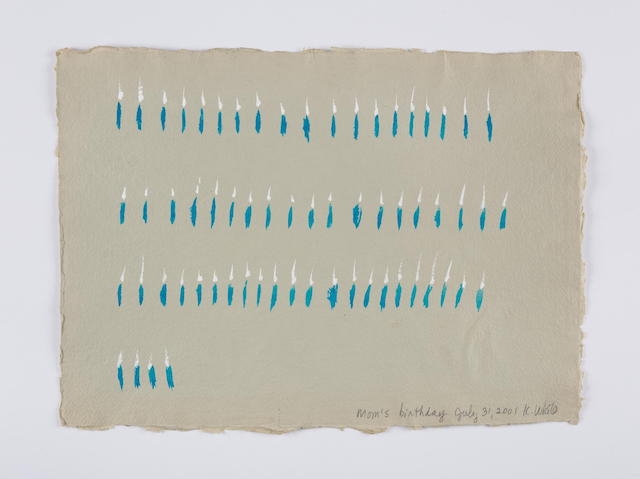

‘Life doesn’t compute,’ the critic Bruce Hainley once offered as a summation of the oeuvre of Hanne Darboven (an armoury of endless looped scrawls and unequivocal equations, neatly inked on graph paper and filling up calendar grids). One is reminded of the resolute will with which the German artist produced those obsessive ledgers when viewing Kathleen White’s A Year of Firsts (2001), a suite of 40 drawings in paint, ink, pastel and other media on rag paper, many accompanied by an explanatory pencilled caption and each marking a separate day in 2001. The New York-based artist is perhaps best known for her work commemorating friends lost to the city’s AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 90s – a time in which death appeared to strike at random, picking off members of her community without logic or reason. White, who died of lung cancer in 2014, created these modest works on paper in response to the concurrent death of her father (also to lung cancer) and loss of her brother to a prison sentencing in March of that year. The spare, abstract compositions, arranged in chronological order to span three gallery walls, track her emotions on each date. The paintings commemorate ‘firsts’ not in the sense of new beginnings, but rather in terms of the inaugural steps of a slow march ever farther from an irrecoverable past. Their oblique, sometimes tortured scrawls are testaments to the impossible task of wresting sense from tragedy.

Some dates are milestones: White dedicates one painting to her brother’s first birthday spent incarcerated, another to the first time she found herself forgetting and then remembering that her father was gone. Others are prosaic: the first trip to the corner store since his death; the first Labor Day since his passing. These are interspersed with still other drawings dedicated to loved ones lost to AIDS as well as to her sister Charlene, who was killed by a drunk driver in 1998 and whose death haunted the White family. In each, the artist’s marking of the date in question is overshadowed by the gesture’s seeming insufficiency in the face of the passage of time. In another week, it would be a year and a week since the anniversary in question. Would the date’s resonance still hold?

While Darboven’s precise notations are intentionally oblique and incoherent, as if to underscore the futility of attempting to create order out of trauma (in the senior artist’s case, the experience of witnessing the Second World War and its aftermath), White’s are tender and confessional in their frank admission of personal loss. Even more direct, albeit less overtly autobiographical, is her four-channel 1988 video installation (mounted in the centre of the gallery), The Spark Between L And D. On four monitors, which play the looped 11-minute video at varying points in its duration, the artist is shown, in a nurse’s dress emblazoned with international flags, intoning the chorus from On Broadway and slapping her face until it appears to bleed profusely. She then proceeds to bandage the entirety of her body while continuing to sing, until her mouth is muffled by gauze, stopping only when she can no longer move. The application of these bandages, stopgaps that do nothing to redress the violent assault upon the artist’s body in the video’s opening, and which ultimately silence her into submission, is an obvious allusion to New York City’s inadequate response during the 1980s to its escalating AIDS crisis. Yet the work additionally calls to mind inner turmoil and the desire for self-harm exacerbated by cosmetic attempts to suppress this urge. Perhaps it also speaks to personal guilt.

While The Spark… finds White fuelled by anger, in her subdued, elegiac paintings of 2001, she has transitioned to – if not acceptance – acknowledgement of the inherent chaos of loss.

Kathleen White: A Year of Firsts at Martos Gallery, New York, 14 December – 27 January

From the March 2018 issue of ArtReview