Construction time again

The streets remain a sump in the aftermath of psychotic pyrotechnical New Year’s celebrations. Spent rockets like discarded cigar stubs litter the pavements along with shards of smashed glass. Empty green bottles of yellow-labelled Veuve Clicquot rest beside old statues of Marx and Engels: the markers of ideological opposites sit together in an uneasy truce. The Berlin Wall, astonishingly, has now been down for a longer time than it was up. More than 28 years have passed since the 155km Antifaschistischer Schutzwall – the so-called Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart – separated the city into two halves. So what has changed? Everything and nothing.

Gentrification means there are fewer buildings pockmarked with shrapnel wounds, but look at the electoral map of the city following the federal elections of 2017 – the left still controls what was East Berlin, the centre-right the West. Apart from voters in the outer eastern suburbs, nearly everyone here regards the far-right Alternative für Deutschland as beyond the pale. Berlin’s concerns are different; it is not Germany in the same way that London is not Brexit Britain and New York City is not Trump’s America. But if the politics have remained fundamentally unaltered, the city’s infrastructure is in permanent flux. Berlin is persistently, as Karl Scheffler wrote in Berlin – The Fate of a City (1910), a place ‘condemned always to be becoming but never to be’. The Wall is gone, but cranes remain ubiquitous. Currently under construction, there’s the new U-Bahn extension (U5) buried beneath Unter den Linden and the Rem Koolhaas-designed HQ for press giant Axel Springer. These days the city isn’t the ‘poor-but-sexy’ art factory so beloved of groovy ex-mayor Klaus Wowereit. There’s money now, as evidenced in the enormous converted bunker where the grandiloquent Boros Collection resides. But what about the smaller galleries, those fabled gems, sharp as diamonds, in which the facets of the cutting edge were constantly polished?

Eastern promise

Little remains of the old Wohnzimmer – ‘living-room’ – scene of the early 1990s. This centred on Auguststrasse, now upscale, as slick as the tango dancers at Clärchens Ballhaus. As part of the Boros effect, there are affluent collector depots, such as Me Collectors Room, home to Thomas Olbricht’s hoard. Olbricht, an endocrinologist, has a broad collection spanning genres and epochs that includes a selection of contemporary German greats such as Gerhard Richter and Thomas Demand. Currently on show is a terrific loan from the National Gallery of Australia that chimes with his eclectic treasury – a selection of works by indigenous peoples. Gifted colourists abound here, such as the late Mick Namarari Tjapaltjarri, whose Untitled (Rain Dreaming at Nyunmanu) (1994) has the dizzyingly optical impact of a Bridget Riley or Chris Ofili. Up the road is Pauly Saal, a restaurant favoured by the local art crowd, with Murano chandeliers and sculptures by Daniel Richter and Cosima von Bonin.

All of this a far cry from the days when Leipzig’s Gerd Harry Lybke opened his then modest Eigen + Art outpost on this street. At KW Institute for Contemporary Art Lucy Skaer uses high-production values to create sculptures that reference medieval hunting scenes, as with La Chasse (2017). Elsewhere there are Moroccan rugs and interlinked tables in One Remove (2016), a work that, we learn, responds to the abstract qualities of Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves (1931) – which makes one fear that Auguststrasse might smugly mutate into a twee outpost of Bloomsbury. Parallel, on Linienstrasse, is Neugerriemschneider and the large linen wall-weavings of Andreas Eriksson, among them Weissensee no1 (2017). The woody browns evoke the Swedish forest; laboriously constructed, they imply serious Northern graft. Up the street you buzz your way into a Hof where an old DDR block now serves as Galerie Neu. Here there’s a typically cryptic group show called in search of characters… inspired by artist Philippe Thomas and his exhibition at New York’s Cable Gallery in 1987. Imagine a corporate agency that flogs furniture as readymades. One of Klara Lidén’s trash-aesthetic constructions is included, a Styrofoam sofa – Untitled (Quando in Roma) (2017). Here too is a memorable oil painting by Jill Mulleady, Self Portrait (2017), an angry slice of pained Woolfean domesticity showing a kitchen sink stuffed with things needing a wash-up, plus a pink rubber glove, a green scouring brush.

The landscape is changing

Near Rosenthaler Platz, which is now a noisy hub of hostels for young travellers, KOW is showing Ahmet Öğüt’s Hotel Resistance, a laconically smart series of political gestures. There’s a print photo of Angela Davis that those cool kids can freely walk off with, nodding to Felix Gonzalez-Torres – Let’s imagine you steal this poster (2016). This is followed by scale models of houses due for demolition but whose owners have blocked such plans, as with Pleasure Places of All Kinds, Zurich (2017) – a four-storey building with typical Swiss gables isolated on a mound of earth, surrounded by excavations. The videoworks downstairs are accessed through The Swinging Doors, Germany Edition (2009), a gate made from police riot-shields.

Berlin’s artworld now seems obsessed with the West’s decline and fall as seen through the prism of consumer excess

On the broad expanse of Karl-Marx-Allee is Capitain Petzel. Here, where Russian tanks once parked (replaced today by furniture outlets like Bo Concept), is Stephen Prina’s As He Remembered It, a show inspired by memories of a storefront at night in Los Angeles. Another fake showroom interior, then; another jibe at materialism made with manicured materials. Shiny, pink, planklike objects recall John McCracken. Berlin’s artworld now seems obsessed with the West’s decline and fall as seen through the prism of consumer excess. Just off Unter den Linden is the Schinkel Pavillon, where there are two displays. Oliver Laric’s Panoramafreiheit features work based on Max Klinger’s imperious Beethoven monument (1902). Laric has constructed his tribute out of 17 separate 3D-printed components. They look oddly like those Chinese ice-sculptures from the festival held every winter in Harbin. Prepared to distrust the other show at the Schinkel, of Eliza Douglas’s paintings (given the hype surrounding her collaborations with Anne Imhof), I was in fact tickled by it, which is titled Old Tissues Filled with Tears. Douglas, with her scatter of disarticulated arms and a delirious Cookie Monster, succeeds in lightly amusing.

The Brits (and the Belgians) are coming

Round the corner, the former Palast der Republik is just a memory, while the Hohenzollern Palace is being rebuilt and awaits Neil MacGregor’s tutelage. On Museum Island there is a new Pergamon entrance being completed, but the city is asking, with increasing desperation: is there enough money to finish the renovation job? That evening we take in a dance event at the Volksbühne under its new boss, ex-Tate Modern director Chris Dercon. Fears that the radical line favoured previously at the venue will be ditched for a more mainstream approach may prove justified if the ropey performance of Jerôme Bel’s The show must go on was anything to go by. A bloke at the foot of the stage sticks pop songs on a CD player. We get Every Breath You Take (1983) by The Police while a line of ‘dancers’ stand still and stare at us. I imagine that the avid theatre-lovers of the East are keeping a beady eye on Dercon. They’re thinking: I’ll be watching you.

By the Wall

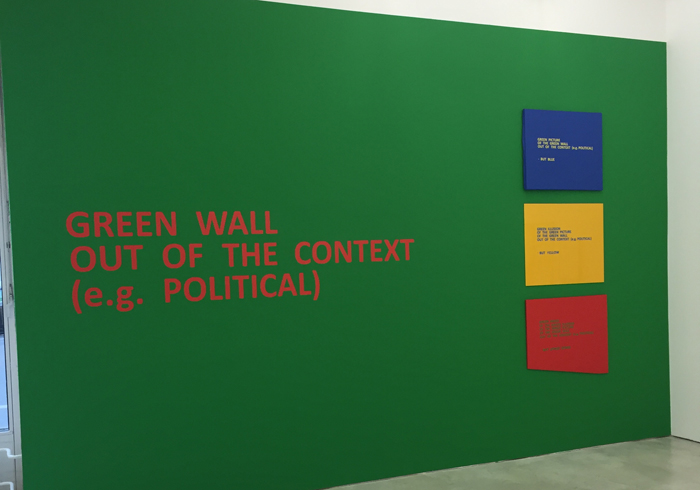

Nothing symbolises persistent tension in Berlin as does the junction of Axel-Springer-Strasse and Rudi-Dutschke-Strasse. The Springer newssheets were said to encourage the targeting of the student movement leader Dutschke before he was shot in 1968. The rightwing press conglomerate wallows in its hollow victory with its aforementioned extension opposite the brilliantly elegant curves of Erich Mendelsohn’s Mosse building. Across the road at Żak/Branicka is Jarosław Kozłowski’s Green Wall (1982/2017) – a polemical work, particularly when sited hard by the old Wall and the Springer empire. The artist’s News Games (2014), appropriately located in the press district, is a line of 17 bags of yesterday’s papers brightened by splatterings of paint in all the colours of the rainbow. Further along Lindenstrasse, the Jewish Museum has a large green road sign at its entrance announcing, confusingly, Welcome to Jerusalem. This proves to be a brilliantly balanced exhibition about the city, and a real curatorial gamble given Trump’s recent pronouncement on its status as capital of Israel. Yael Bartana’s video Inferno (2013) dramatises the destruction of the temple (specifically that of Solomon, in São Paulo) and finishes the show with a hard slap of sobriety. At the Berlinsiche Galerie, Jeanne Mammen’s pungently decadent Weimar drawings square off against the leather-clad sculptural shenanigans of Monica Bonvicini; the latter artist gets spanked. Over in the brutalist church space of König Galerie, Isa Genzken shows more of her showroom dummy mutations. More sneering at shopping, then, this time costarring one of the artist’s familiar copies of the Pergamon’s Nefertiti, here looking glam in shades.

The West is the best?

After many years of mouldering, West Berlin is staging something of a comeback. Contemporary Fine Arts Berlin has re-relocated to Charlottenburg. The photography gallery C/O has also moved from the East and is now at the Amerika Haus, hard by Zoo Station. Here Joel Meyerowitz’s photographs remind us that America’s best days may be past. And at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, a revisionist show (comprising as much documentation as artworks) on the Cold War period reminds us of the city’s schismatic inheritance, and sticks it to the CIA for its (massive and global) interference in the arts. Finding Edition Block is a challenge – the opening of K.P. Brehmer’s retrospective prodding at capitalist realism involves the intriguing sight of gallerist and supermarket heir Alex Sainsbury singing the praises of the late Mark Fisher. There’s still old money here in Charlottenburg, with its gleaming cafés named after George Grosz, the locals indifferent to his scabrous Weltanschauung. The Wall is long gone, but the city still tries to make sense of its mutability. Michael Hoffmann’s new translation of Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), with its theme of urban metamorphosis, is therefore most timely.

Fro the March 2018 issue of ArtReview