Sharjah Biennial 14, 7 March – 10 June

The 14th Sharjah Biennial since the event’s inception in 1993, subtitled Leaving the Echo Chamber, references a place many of us visit regularly these days, whether browsing news or navigating social media’s layer-cake of shouting matches. It’s a zone where a limited range of viewpoints gets heard, thanks to corporate influence and/or because we’re marooned inside self-designed filter bubbles. Meanwhile, as is all too apparent in the ‘real’ world outside, everything slips and slides fearfully: history is fictionalised, borders are redrawn, eco-catastrophe looms. This biennial, subdivided into three shows curated respectively by Zoe Butt, Omar Kholeif and Claire Tancons, isn’t going to be so gauche as to suggest how to ‘leave’ this dangerous safe space (for that, try Jaron Lanier’s trenchant 2018 manifesto Ten Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now), pat answers not being art’s job and, frankly, curators typically not having those answers.

Instead, the project ‘seeks to put into conversation a series of provocations on how one might re-negotiate the shape, form and function of this chamber, towards a multiplying of the echoes within’. Butt’s segment, including Khadim Ali, Nalini Malani, Lee Mingwei and two dozen others, draws frequently on artists from the global south and themes of human movement and the use of tools. Kholeif’s, in the teeth of technology, looks at concepts of temporality and the possibility of slowing down via artists including Stan Douglas, Ian Cheng and Candice Breitz. And Tancon’s, whose contributors include Laura Lima, writer/musician Jace Clayton and Tracey Rose, is concerned with ‘the alternatively dispossessive and repossessive disposition of diasporisation as an aporetic phenomenon of the contemporary’, a sentence you’d maybe have to inhabit your own special echo chamber to write.

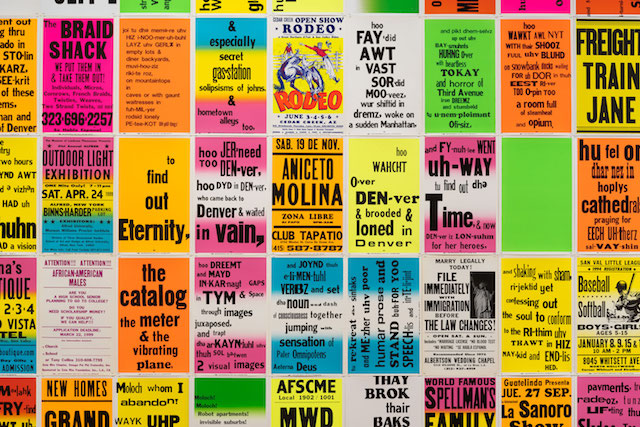

Allen Ruppersberg, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, through 12 May

Obscurantism has not been Allen Ruppersberg’s path, as seen in his retrospective fiesta Intellectual Property: 1968–2018 at the Hammer Museum. The Cleveland-born, longtime Los Angeles resident has, for half a century, sociably reframed conceptual art through the vernacular: visitors to his first solo show, in 1969, titled Location Piece, were redirected from the host gallery to a rented office stuffed with an installation of pop-cultural artefacts, while Ruppersberg’s well-known Where’s Al? (1972) paired up photographs of people – assumedly the artist’s friends – eating, at the beach, etc – with typed texts wondering where he was. Al, in these works, is a trace element displaced into artefacts of the mainstream, just as he is in Al’s Grand Hotel (1971), a fully functioning Hollywood hotel/art project open for a month, and The Novel That Writes Itself (1978–2014), a slanted summary of the artist’s lifetime via 400 letterpress posters in which colourful gradients backdrop texts ranging from actual advertisements for concerts, wrestling matches, etc, to scraps of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl (1956) and random slivers of speech. For the Hammer, Ruppersberg’s central themes are avowedly ‘movement between places, presence and absence, the book as object and subject, memorials, and self-portraiture’: those interests, the artist demonstrates, needn’t sacrifice seriousness when they’re treated breezily.

Brian Calvin, Almine Rech, Paris, 9 March – 13 April

Staying West-Coastal momentarily, the quick way of describing Brian Calvin might be to call him the slacker Alex Katz, with a dash of early Lucian Freud. He emerged during the mid-1990s with crisply painted, cartoon-bright portraits of long-haired, androgynous, fat-lipped, zonked-looking countercultural types, generally doing pretty much nothing. This fact underlined Calvin’s resistance to narrative, though one might glimpse a spectrum of emotions – not least amorphous anxiety – sliding across his bug-eyed young faces. While Calvin occasionally reorients to Californian landscapes, or just mouths (by which he’s clearly captivated), he’s been remarkably consistent over his career, to the point where his paintings feel like old friends, small modulations in his style having disproportionate effects. Here the focus is on paintings of twins, with accompanying drawings.

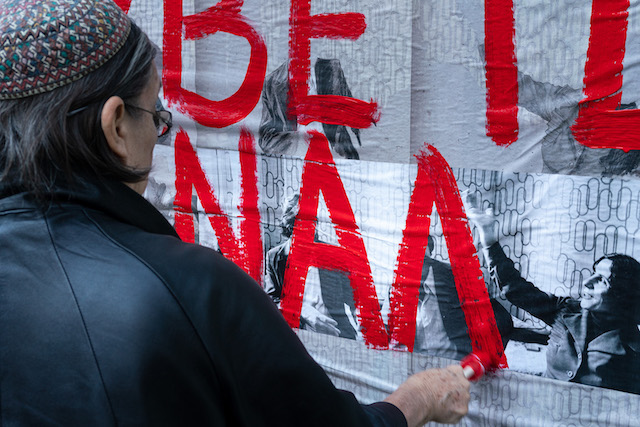

Nil Yalter, Ludwig Museum, Cologne, 9 March – 2 June

Over the past dozen years, particularly since her inclusion in the touring show WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (2007), and not a moment too late given that she turned eighty last year, Nil Yalter has been increasingly recognised as a key figure in the canon of feminist art. And an adaptable and footloose one, too, even leaving aside that her Wikipedia entry contains the sentence ‘In 1956 she travelled to India on foot while practicing pantomime’. Her work ranges from videos such as The Headless Woman or the Belly Dance (1974), in which the Egypt-born Turkish artist wrote text from René Nelli’s Erotique et Civilisations (1972) on her navel and then belly-danced to animate the words, to 1990s works expressed via 3D technologies and interactive CD-ROMs. The key piece in her oeuvre, though – and likely to be a highlight of this first major retrospective, Exile Is A Hard Job – is probably Temporary Dwellings (1974–77), 12 panels mixing Polaroids, drawings and text and delving into the difficult lives of immigrant communities in Paris, New York and Istanbul: a work that was timely then and, for obvious reasons, hasn’t really dated.

Diane Arbus, Hayward Gallery, London, through 6 May

Three years ago the Met Breuer put on a stellar show of Diane Arbus’s early work, a hundred or so small black-and-white photos that repeatedly did what great portrait art does: collapse time, put a gone person in front of you, their liveliness summarised and restored. If you missed that exhibition, it’s now coming to London, with Diane Arbus: In the Beginning constituting the first UK showing of the great photographer’s work in a dozen years. It focuses on the first seven years of her career, and while some of the work feels canonical – images of female impersonators, for example – it is frequently less sensationalist, quieter and subtler, than the images of outcasts, eccentrics and circus performers she’s known for: grainy faces glimpsed in passing taxis, infinitely serious-looking kids, top-hatted old guys in flophouses, performers paused in dressing rooms. There’s nary a dud, as the cliché goes, among these intrepid studies, which set the stage not only for Arbus’s own career but of so many photographers who’ve dwelt on the social margins since. (Remember to pronounce her name Dee-anne.)

From the March 2019 issue of ArtReview