Reinhard Mucha, Sprüth Magers, London, through 11 May

Arbus’s sustained no-show in London, though, is nothing compared to that of Reinhard Mucha, who specialises in making audiences wait and whose show at Sprüth Magers is his first exhibition in the capital for 30 years. For the pointedly titled Full Take, the hermetic and reclusive German surveys the last four decades of his own production, which has often involved elliptical, meticulously constructed things that look like gorgeously wayward furniture and circle around the interrelated subjects of time, preservation and change. Mucha’s cabinets, drawers and vitrines contain all manner of ephemera, often with a bureaucratic tang that relates the work to Germany’s postwar ‘economic miracle’, though not always. Here, for example, expect works such as Oderin/Untitled (MÄNNER FRAUEN) (1987/1981), an installation combining formerly separate works that unites crisp white-on-black-glass text paintings of ‘Männer’ and ‘Frauen’ and a grey sculptural ensemble, the whole vaguely suggesting an extremely high-end and abstract restroom.

Jeffrey Gibson, New Museum, New York, through 6 September

Sculpting with time, part II: as artist-in-residence at the New Museum, Jeffrey Gibson is both producing something in the unfolding present – garments, essentially – and harkening back to another era. The clothing he’s making, which is going to be activated by photographs and performances, draws on handcraft practices by indigenous tribes before the Europeans turned up: ‘Southeastern river cane basket weaving, Algonquian birch bark biting, and porcupine quillwork’ (Gibson, it bears noting, is of Choctaw/Cherokee ancestry). Judging by his kinetically colourful previous work, we might also expect it to by hypercolourful, as effervescent to look at as it’s underlaid with sadness and – being influenced by Oswald de Andrade’s 1928 ‘Anthropophagic Manifesto’, with its advocacy of the reuse by the colonised of their colonisers’ culture – a pointed merging of older and newer aesthetics, the rural meeting the catwalk.

Eric Baudelaire, Barbara Wien, Berlin, through 13 April

Eric Baudelaire’s practice adapts itself to both galleries and cinemas: he makes what appear to be artworks (photographs, installations, etc) and feature-length films. While for his previous show at Barbara Wien the Salt Lake City-born artist – nominated for the 2019 Marcel Duchamp Prize – showcased his art side, here he presents his 2017 film Also Known as Jihadi. It’s art, then, although that distinction matters less than the ones the film presents between representing and not representing, understanding and not understanding. Drawing on the example of Japanese filmmaker Masao Adachi’s 1969 film AKA Serial Killer – which never showed the convicted murderer Norio Nagayama but rather skewed to the places he’d been – Baudelaire builds up a portrait of the radicalised ‘Abdel Aziz Mekki’ (not his real name, though the film is based on a real person) via key landscapes in his life: the Parisian suburb where he grew up, and then later Egypt, Turkey, Syria For Baudelaire, this kind of circumspection is necessary in order to avoid simplifying the story or reducing it to a simplified understanding, or, indeed, any understanding at all: ‘it belongs to us to compose an affective character through our projections’. Meanwhile a series of related silkscreens, collaboratively made and exploring the relation between art and current events, might help this hazy process along.

Jakob Kolding, Martin Janda, Vienna, 8 March – 20 April

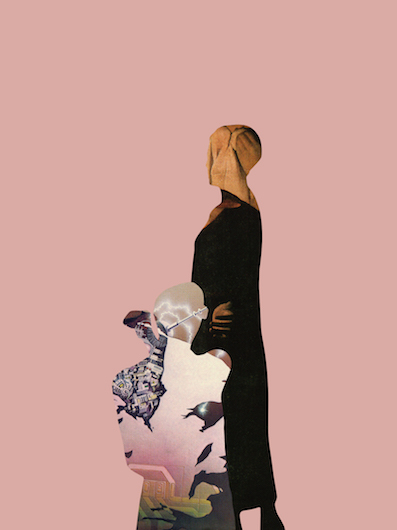

If Jakob Kolding compares his artistic practice to sampling – and he does – then it’s fitting that the dense patchwork of source images in his new show, Pieces, includes Public Enemy. The Denmark-born, Berlin-based artist’s layered prints here, designed to look almost opaque and monochrome at first blush and consisting of a panoply of pictorial elements – Spiderman to Caravaggio, Bernini to jazz drummer Milford Graves – might be visual parallels to the Bomb Squad’s vintage productions for the legendary hip-hop crew; the details have to emerge from a surface of interspersions that can feel almost sheer, though Kolding’s art is more darkly luscious than it is raw. Also on show here are cutout silhouettes filled in with an image from a different source; between these and the prints, Kolding is leveraging ambivalence, estrangement, fragmentation, symbiosis and the coexistence of difference, not for purely formal reasons but to prioritise interconnection over isolation. No accident in this regard that his works feel digitally massaged, but end up leaning contrariwise to the divides that screen life sets up.

Europa Endlos, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, 22 March – 11 August

Speaking of fragmentation: the Kunsthal Charlottenborg’s Europa Endlos, with its double-edged, approximately Kraftwerk-referencing title, opens a week before – at the time of writing – the UK is projected to leave the European Union, and close to the European parliamentary elections. That’s obviously no accident: ‘The exhibition will provide fuel for reflections about the current state of Europe and the future role of the EU,’ write the organisers. Meanwhile, for what is likely to be a melancholy affair offset by a feeling of regrouping, they’ve assembled a starry list of talents from Europe and occasionally outside, from Olafur Eliasson to Fischli/Weiss, Monica Bonvicini to Bouchra Khalili, Jimmie Durham to Wolfgang Tillmans and – no doubt with something trenchant to say about Brexit – Jeremy Deller.

From the March 2019 issue of ArtReview