John Quin on crime and punishment

‘Good artists borrow, great artists steal’: whether Picasso said this or not, we can be pretty sure he didn’t mean pilfering down at the mall. But looking at the two black-and-white photographs that comprise Smile (1971), one suspects Alain Bizos took those words quite literally. The first photo is of an old surveillance camera and a sign that reads SMILE SHOPLIFTERS YOU ARE ON CAMERA. It sits above the second, a full-faced shot of Bizos grinning.

The real action begins with Vol des lettres V.O.I. (1970), six photographs that show the artist stealing three large adhesive letters that spell out the French for ‘theft’, ‘steal’ and ‘flight’. An emboldened Bizos then graduates to larger sporting items – Vol du jeu de croquet (1971) – and a suitcase, Vol de la valise (1971), whose documentation also captures Bizos legging it down a New York street. These works, strongly recalling early conceptual pieces by Joseph Kosuth, have three components: framed documentation of the action, the photographs of the thefts themselves and the actual item stolen. (Naughty.) With Vol du spot (1971) the joke is intensified by the fact that the nicked light illuminates the work.

These purloined goods implicate both the gallery as ‘fence’ and any putative buyer as a receiver of stolen goods. Proudhon’s notion of all property being theft is thus cheekily and amusingly referenced by enfolding others in a criminal conspiracy. Bizos made these works in the aftermath of the protests in 1968 and the France of JeanLuc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967), with its cell of student Maoists. With Bye-Bye Mao (1976) Bizos charts the declining intellectual influence of Maoism in Paris – plus by extension the triumph of the moneyed bourgeoisie – by showing five posters illustrating the progressive degradation of the Great Helmsman’s image as it is ripped o¬ a hoarding from left to right.

Bizos is clearly still something of an angry soixante-huitard. Mariane-Colère (2010), 48 photographic portraits of young women wearing blue or red Phrygian caps, refers to the republican symbol of Marianne. They frown or scowl, some bare their teeth; a few have their protective glass shattered. For Bizos the Fifth Republic is a conflicted place: the republican icon of the left has been appropriated by the gilets jaunes movement and even coopted by senior politicians into the ludicrous debate over whether burkinis were un-French.

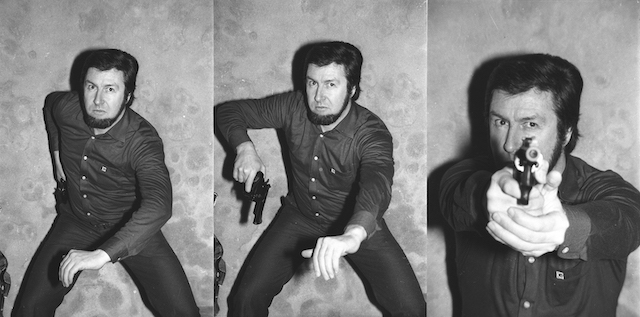

Art about crime and punishment: Bizos ups the stakes with the most surprising body of work here, which features one Jacques Mesrine. Not knowing anything about Mesrine before seeing Bizos’s pictures of a bloke making insolent ‘up yours’ gestures (Le Bras d’honneur, 1979), I took them to be a parody of macho silliness. Le Tir, Jacques Mesrine (triptych) (1979) depicts a figure reaching for his holster, removing his pistol, then pointing the barrel straight at your face. Another photograph, La Guillotine (1979), shows Mesrine’s head protruding from the bottom of a cardboard box, his eyes comically staring upwards – he’s playacting.

And then the reveal, for those unfamiliar with French crime stories: Mesrine was the Ronnie Biggs of France, a Clyde Barrow type, an actual bank robber on the run. He took the piss out of the police and became something of a hero to Bizos and The People. You look again at those determined eyes as he aims that gun and realise that Mesrine had done this for real. In the year the last photo was taken, the police shot him 15 times in his gold BMW on the streets of Paris, an extrajudicial killing. He was forty-two. That decapitation picture was a prophetic gag. The press printed images of his slumped body, but this time it was no act.

Alain Bizos, Politically Incorrect, Polka Galerie, Paris, 15–25 January 2020

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview