Huma Bhabha is careful when discussing her art. She reveals little of her intentions, preferring to affect her viewers in nonlinguistic ways. At times, she speaks of what she refuses – eg, the reading of her work through her identity – and, like a subtractive sculptor, she carves away unwanted interpretations, while we, the viewers, are left to behold the remains. Fittingly, Bhabha leaves a fair amount of her work untitled, and the titles she does assign, especially to her shows, often hint at the unknown – We Come in Peace (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2018), They Live (ICA Boston, 2019), Other Forms of Life (The Contemporary Austin, 2018) – with references to aliens, horror films and the supernatural. This is an artist who places imagination at the forefront of her practice, and every piece seems to add another character to her dark, fantastical underworld.

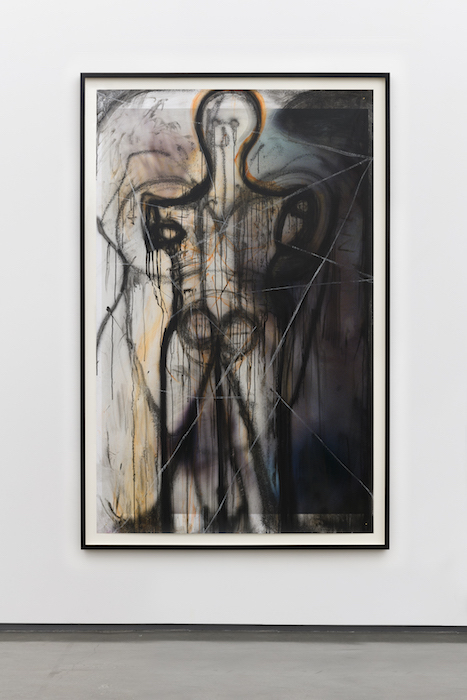

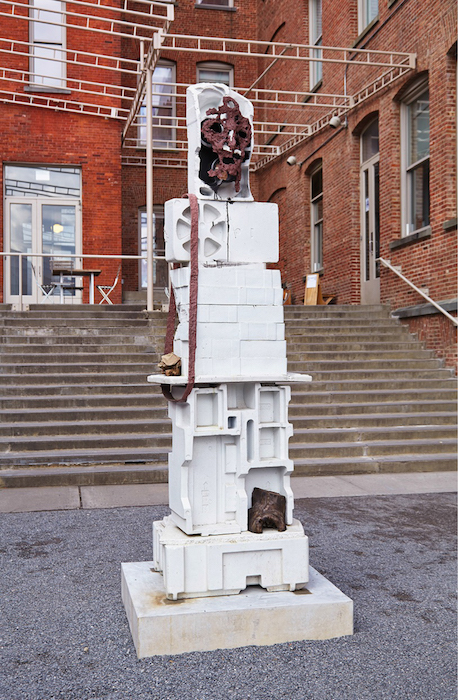

Bhabha’s work is almost entirely figurative, from towering statues to collages to paintings on paper to floating heads on walls. Her exhibitions are populated with creatures that recall vengeful gods – humanoid in form, but not in spirit. As with Giacometti, the energy of her mark-making is most intensified in her faces, which wear expressions that recall the haunted grins of Chinese Guardian lions, the icy stares of Congolese wooden masks, the frozen agony of Francis Bacon’s popes. These idols appear like fetishes from antiquity, and Bhabha’s primary palette encourages this false history: black burns, oxidised rust, murky purples, speckled dirt and startling white. And yet her favoured materials are the immortal polymers of mass production, especially chunks of Styrofoam and plastic, which evoke the dystopic junkyard of the future.

Born in Karachi, Bhabha now works in an old firehouse in what she calls the “extremely urban” city of Poughkeepsie, New York. She moved there in 2002, with her husband, the painter Jason Fox, to escape the high costs and distracting competition of New York. I planned to visit her there in the fall, but she cancelled after feeling a bit overwhelmed with work. So we spoke two months later, on the phone, while she was in a Los Angeles hotel room. She had just installed her untitled solo show at David Kordansky Gallery, and was recovering from an unfortunately timed illness. She sniffled throughout our talk, but her mental acuity was undimmed.

Unpopular interests

ROSS SIMONINI Do you still look at a lot of art?

HUMA BHABHA Seeing my peers is very important to me.

RS It’s funny, a lot of artists don’t feel that way. They stop seeing shows.

HB You have to stay aware of your community. It’s another way of being in reality.

RS You mentioned that you’re not feeling so well right now. What do you do when you’re sick?

HB Just sleep. I brought a book with me but couldn’t read it. The Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories, edited by Jhumpa Lahiri. Seemed like easy material for a trip.

RS Do you read much? I always hear Philip K. Dick associated with your work.

HB I read those a while ago. I watch a lot more science-fiction films than I read now, and 1980s horror movies – before they started with CGI. Early Cronenberg. James Cameron films. Aliens and The Terminator are classics for me. I watch a lot of film and TV. I like old black-and-white movies also.

RS I noticed the film noir The Mask of Dimitrios [1944, starring Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet] is used in one of your new titles. I just watched Laura and The Third Man. Now I’m going through all the Philip Marlowe films.

HB Great movies. Robert Mitchum is good.

RS You were watching a lot of this work when you were growing up in Pakistan?

HB American culture was around, and I just folded it into my culture. It was like speaking two languages at once. I’m comfortable speaking both languages in one sentence. It’s like that.

RS Do you read much horror?

HB Just the classics. Dracula and Frankenstein, which is amazing.

RS I still can’t believe Mary Shelley wrote it at nineteen. The same age you left Pakistan for America.

HB When you’re young, you make the most important choices of your life.

RS What were yours?

HB I met the person I would spend the rest of my life with, and I made the choice to be an artist, pursuing it even though it wasn’t bringing in any money, or shows, or any promise of career success. It took a long time for all of that to come.

RS It felt like a long time to you?

HB It took 15 years after graduating to get my first solo show in New York. Many people I know stopped being artists in that time. They grew out of it, they said. And my work was not fashionable when it was supposed to be. I wasn’t interested in appropriation, which was the 80s, or relational aesthetics and identity, which was the 90s. For me, being original is most important. So my work was dismissed, because I wasn’t doing what other people were doing. It allowed me to do what I wanted to do and to build up my own personal mythology. I could develop interests that were not popular.

RS What other jobs did you work in that period?

HB While I was in grad school at Columbia [University], I worked for an artist for four years. Then I worked at a translation agency as a secretary for four years. Then I got some part-time jobs for graphic designers. Then I decided to take some time o. working, and it happened to be then that I finally got some recognition. I’d been in many group shows but I couldn’t find a gallery to represent me. In 2004 I got my first solo show in New York [at ATM Gallery], though I had also showed at a gallery in Los Angeles that didn’t exist for long. I also got a New York Times review, which put me on the map. Then I was in Greater New York [at PS1] in 2005.

RS Did the recognition change the work for you?

HB I made a lot more work in the last 15 than the previous 15 years, certainly. I had more opportunities, and I met them.

The shuffling

RS Do you have a lot of emotions while making the work? Is it an act of passion?

HB Not so much while I’m working. I spend a lot of time just looking at my work. But the work is emotive.

RS Are you drawn to the horrific?

HB I’m looking for beauty, but that is very different for many people. Gore can be beautiful. I just like intensity. I’m interested in the genre of horror, and I’ve absorbed that into my work. I don’t want to scare somebody. But life is pretty horrific. It keeps us all horrified. It never seems to lessen. We’ve been in a state of war for 20 years. That’s why the younger generation is freaking out, they know they are getting screwed.

RS Is this generation uniquely screwed?

HB Probably not. You know, politics never came into the conversation before. Here, in the States, people never talked about it. Now they do, because things are bad. Things weren’t great before, but they were OK enough that it didn’t affect them. People could be oblivious to it.

RS How was it different when you were coming up?

HB Well, people weren’t looking for younger artists to speculate on. I got a better education working for an artist than I did going to Columbia.

RS Who was the artist?

HB You probably don’t know him. His name is Meyer Vaisman. He was a contemporary of Ashley Bickerton, Richard Prince, Peter Halley. He had a gallery [International With Monument] where he showed these people. It’s funny, most people don’t know his name now, but he was quite an art star then. He worked with Castelli and Sonnabend. He’s still making work, but he lives in Europe. Some people survive the artworld. Some don’t. There’s always a shuffling.

RS Do you think it’s a random shuffle?

HB It always has to do with the quality of your work. You can do all the networking you want, but everything is reevaluated. Even dead people. We look back and wonder: was this person as good as we thought? But one of my favourite artists is Rembrandt. The older he got the better he got. That’s rare.

Always be insecure

RS To me, your work suggests an alternate reality.

HB Maybe it’s the same reality, we just can’t see it.

RS Do you have a specific reality in mind?

HB For me, it’s more about the mark, the material. I do have my own mythology, but I keep that to myself. You respond to it emotionally, but I’m not going to lead you there. I might give you a hint with a title. But sometimes a title just makes it humorous. I think there’s a lot of humour in the work, it’s just a private kind of humour.

RS You sound resistant to language.

HB It’s not my forte. I’m uncomfortable with language. I would not put a text next to a work. I use my hands. I want you to feel.

RS Do you enjoy that mystery around the work?

HB Yeah. It allows me to imagine, and I think imagination is something that people in the artworld don’t consider much.

RS Do you think many artists overly discuss their work?

HB Sure. But I don’t even go there. I just look at the work. I respect conceptual work, but that’s not what I do. I don’t even make preparatory drawings for my sculptures. My work is very intuitive. I’m a formal artist.

RS Do you and your husband talk about art much?

HB Oh yes. I’m very lucky to have found someone like that.

RS Will you open up to him about your mythology?

HB Oh yeah, totally. When you are comfortable with someone, you can sound foolish. We can talk about movies and whatever weird ideas I have.

RS Did you grow up with much religion?

HB My parents weren’t super-religious, but they weren’t nonbelievers either. There’s this idea about that part of the world, that it’s more religious, but it’s the same as here. I’d say it’s even more conservative here now.

RS What about now? No religion?

HB I don’t practise anything. Organised religion doesn’t have the answer to anything. I grew up believing more, but as I grew older I saw that religion was only hurting people.

RS Do you believe in anything outside of religion?

HB Sure. Spirituality and stuff like that.

RS Any superstitions?

HB None.

RS Do you have any beliefs around the ideas in your work, like say extraterrestrials? Or do you not engage with it that way?

HB I don’t engage with it like that. I just use it as a way to stimulate my imagination. And the work does relate to other issues, like militarism. The work is about now, not the future or the past.

RS Would you say your imagination is more or less developed now than in your youth?

HB I think the more you experience, the more connections you can make, and that allows you to strengthen your imagination.

RS One of the uses of horror, or fear, is the way it can stimulate the imagination.

HB I like that. I want people to have a physical sensation in front of my work.

RS What are you afraid of?

HB Regular stuff.

RS Like death?

HB Illness. My family members went through that. You don’t want to be sick for very long.

RS And you’re sick right now. Oh no!

HB [laughs] It’s just the flu. I’m not going to die. It’s just been lingering. The opening is the day after tomorrow and I’ll be fine by then. I think I caught it in the doctor’s office. I normally stay pretty healthy.

RS They say that hospitals are one of the top causes of illness and death.

HB Exactly. Because you never know who is carrying what.

RS You speak so practically but…

HB I’m crazy otherwise [laughs]. I’m not a crazy person in life. Some people are. I’m open but there’s a lot of practicality in my work process.

RS Styrofoam is practical.

HB I use the packing-material kind and the coloured kind used for insulation. For me, it’s like marble. I wasn’t trained as sculptor so I can’t carve marble or stone. Styrofoam is sturdy and light. It made sense to use light materials when you move things by yourself. My process is about a series of practical decisions.

RS Is it a dangerous material to work with, in terms of your respiratory system?

HB Less than resin. Less than fibreglass. I just wear a mask.

RS From the outside you seem to be at a good point in your career. Does it feel that way?

HB Yes. I feel good about the work. I’ve had many great opportunities and they’ve all brought me to new places. As an artist the most important thing is to be aware of what you’re doing. And to always be insecure. Never take anything for granted. My husband says it’s good to stay insecure. It’s a healthy thing.

RS Do you feel stress around the success?

HB I try not to. If I ran out of ideas, that would be bad, but I still have plenty.

An exhibition of new sculptures and drawings by Huma Bhabha is on show at David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, through 14 March

Ross Simonini is an artist and writer based in New York and California

From the March 2020 issue of ArtReview