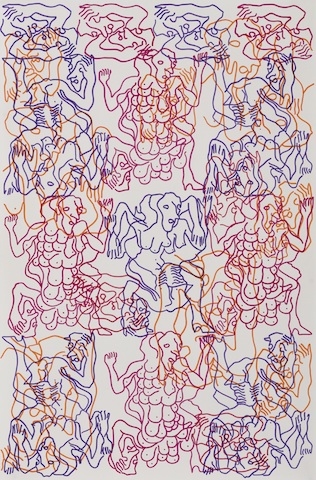

Carlos Amorales at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 23 November – 17 May

It’s appropriate that the first-ever European retrospective of Carlos Amorales’s work is taking place in Amsterdam. It was there that he studied, at the Gerrit Rietveld Akademie and the Rijksakademie, and there that Aguirre Morales took up what he’s called his ‘stage name’, inspired by Mexican lucha libre wrestlers. Borrowing and lending have been central to Amorales’s career ever since. Artists, wrestlers and strangers have adopted his nom de guerre and a bespoke mask for fights and performance, while a digital image bank, Liquid Archive (1999–2010), made with assistants using vector graphics, has constituted the basis for much of his production: it’s also been shared and migrated into record covers, fashion, etc, as part of Amorales’s wider reflection on, and staged sparring with, pop culture, neoliberalism and what the artist calls ‘the globalized assembly-line’. The Stedelijk show, timed to coincide with Amsterdam Art Weekend, will track back through all of that via paintings, drawings, textiles, videos, animations and more, across 14 rooms of the museum, culminating in a new work made specially for the exhibition. Whether there’ll also be fighting – at least of the organised kind – is unconfirmable as we go to press. Of course, the meeting between art and nonart isn’t always disreputable; indeed, the aim of many artists over the past couple of decades has been to eliminate any vestigial line between art and nonart, even if that sometimes means artists making shitty fashion lines (or worse, Banksy).

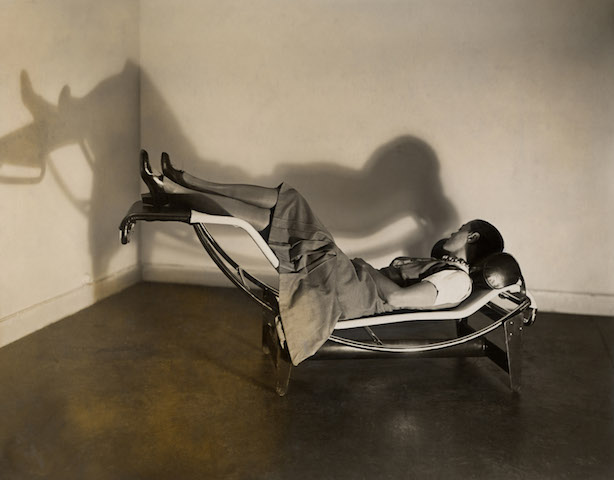

Charlotte Perriand at Foundation Louis Vuitton, Paris, through 24 February

Anyway, we’re taking this generalised dissolving as an excuse to showcase architect and designer Charlotte Perriand, not least because she was a badass. Early on – she lived between 1903 and 1999 – the Frenchwoman collaborated with Le Corbusier, with whom she shared ideas that there was an art to living and one’s environment should support it. (Among other collaborations with Corb, she later designed parts of the Unité d’Habitation housing developments.) After going on to work with Jean Prouvé and becoming immersed in leftist causes and egalitarian design, she pivoted away from expensive materials towards woods and handcraft, and went on to design everything from student housing to ski resorts. Among her classics – made while she was in Le Corbusier’s studio – is the LC4 chaise longue, designed to be deeply sympathetic to the body’s contours. (Albeit, as the initials suggest, pointing to a name other than her own.) In Paris, in a show marking the 20th anniversary of her death, her career will be reexamined via reconstitutions of her environments, an accent on the feminist slant of her work and – bringing us fortuitously back to artistry – works of art chosen by her for her living spaces.

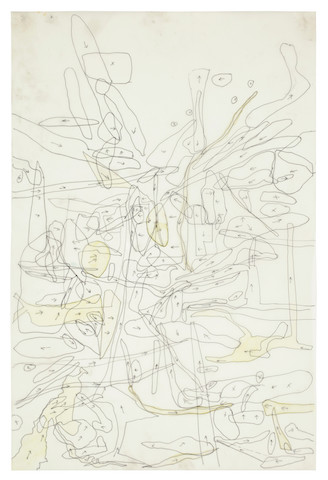

Carroll Dunham and Albert Oehlen at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 30 November – 1 March

Carroll Dunham and Albert Oehlen apparently each see the other as the world’s best living painter of trees. (Alex Katz could not be reached for comment.) Their first-ever show together maybe doesn’t constitute a bout to settle that, and we might not expect the artists to arrive at the opening wearing masks, laceup boots and spandex. But it gives the rest of us a chance to absorb, and compare, the work of two of the more influential daubers of their generation. Oehlen has travelled from self-described ‘bad painting’ in punky, neo-expressionist 1980s West Germany to his present course of near-beautiful, digitally assisted, faintly cynical semiabstractions. Dunham, in the same era, has pursued an obliquely sexualised, cartoonish path in something like the other direction, from abstraction to biomorphic figuration populated by odd characters. As tree painters, they also diverge. Oehlen’s are wintry, leafless silhouettes that serve as graphic motifs within blocky and smeary abstracts, Dunham’s windblown and leafy or felled. One might take a psychological attitude to this – two lions in autumn ruminating on passing time via a useful motif – or just enjoy the spectacle of transatlantic artistic cousins who can handle paint superbly but are allergic to the self-seriousness that might come with that.

Julie Mehretu at LACMA, Los Angeles, through 17 May

The aerial view of a practice occasioned by a midcareer retrospective couldn’t be more apt for Julie Mehretu, since the 35 paintings and 40 works on paper from 1996 onwards at LACMA are likely to be characterised by her signature febrile abstracting of topographies of the urban landscape. The Ethiopia-born American painter’s works overlay figuration and nonrepresentation, blending maps, snippets of architecture, weather charts and more in teeming, omnidirectional, dizzying compositions that contain multitudes but are also specific. Political consciousness – and the imprint of geopolitics and capitalism on places and people – is at the heart of Mehretu’s project, which she views as a form of resistance and embodied possibility. See her three Stadia (2004) paintings, which merge architectural plans of stadiums, quotations of corporate logos and flags of the world; Mogamma: A Painting in Four Parts (2012), which spins off from the layout and buildings of Tahrir Square in Cairo, that public space central to the Arab Spring; or recent paintings that collide images from the 2017 white nationalist ‘Unite the Right’ rally in Charlottesville, California wildfires, Muslim Ban protests and other evidence of our grimly fractured moment. Expect this show, then, to be as timely as her work itself.

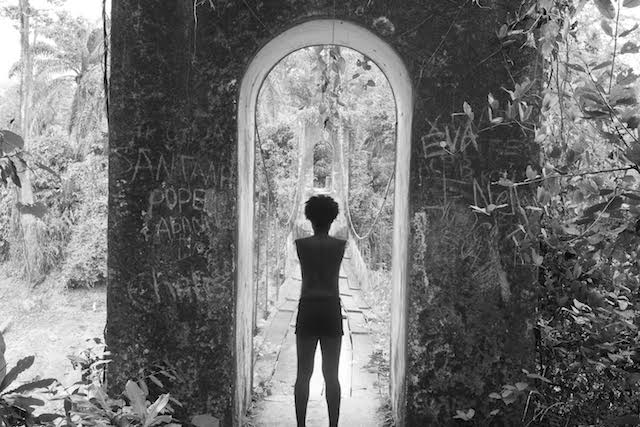

Diaspora at Home at Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, through 31 January

Earlier this year, Bisi Silva, the forward-thinking curator and founder of the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos, died aged just fifty-six. The institution is paying tribute to both her and her desire to create new cultural networks throughout Africa with Diaspora at Home, a collaboration with Paris’s KADIST that is, in turn, part of the latter’s larger project of international collaborations. The nub of the show, for which the eight included artists produced new works in Lagos and entered into dialogue with the local art scene, is that migration and mobility are pretty much the norm within the African subcontinent (and have been since the tenth century, beginning with the trans-Saharan gold trade). Here, some artists bring distant narratives to the city, such as Em’kal Eyongakpa’s recordings of water and sounds from the underreported Cameroonian civil war, Chloé Quenum’s exploration of ‘the transnational journey of fruits from the market of Lagos’ and Bady Dalloul’s unpacking of the history of the city’s North African and Middle Eastern communities. Adding to the sense of dialogue, the show enfolds artists’ residencies and a series of talks and colloquies.

Anna Daučíková at Project Arts Centre, Dublin, through 18 January

On Wikipedia, Anna Daučíková is described as ‘the first Czechoslovak feminist and queer female artist’. On Documenta’s website, meanwhile, Paul B. Preciado says that one could call her that, ‘except that [her] work problematizes the terms of this seemingly simple enunciation. Who can claim to be first? Who can act in a nation’s name? What does it mean to be feminist? Can a subject to whom female gender has been assigned at birth resist becoming female? Who qualifies as an artist?’ Arguably addressing all of this, Daučíková’s art since the 1990s in particular constitutes a space in which she’s observed and questioned, both from inside and out. A moving target, she’s moved from automatic paintings questioning authorship (while working as a glassblower and being what Preciado calls an ‘undercover lesbian’ in 1980s Moscow) to cofounding queer feminist journal Aspekt, to making installations, performances, textual documentation and videos that explore and confound normativity and often focus on sex and aspects of ideological control, as enforced by state surveillance to the Catholic church (eg Scene Book, 2014, an A4 pad containing 36 observational reports, a formalised piece of spying, seemingly by and on the artist herself). In Daučíková’s first show in Ireland, expect a mix of recent and older works, including Thirty-three Situations (2015), which she describes as somewhere between a police dossier, a medical history and a ‘stigmatic script of the individual situations’.

The Assembled Human at Museum Folkwang, Essen, through 15 March

Postinternet art may have lately seemed more like a punchline than a legitimate if evanescent art movement, but the Museum Folkwang is bringing it back. Well, sort of. In The Assembled Human, a few of the better artists drawn into its latterday orbit form the endpoint of a 150-year continuum of mankind’s engagements with the mechanical, ie from the Industrial Revolution to the Information Age, or whatever our current mediated hellscape is called. Naturally, expect the tone to be less than sanguine, since for all that technologies have given us they’ve also taken away – and, from the spinning jenny to A1 and social media, one thing diminished in particular has been a sense of agency, freedom, individuality. In any case, the artist list here is excellent, ranging from Marcel Duchamp and Fernand Léger to Jon Rafman and Ed Atkins, stopping off at figures including Rebecca Horn, Maria Lassnig, Max Ernst and Tony Oursler along the way.

The Extended Mind at Talbot Rice, Edinburgh, through 1 February

Meanwhile, a counterposition might be glimpsed in The Extended Mind, at Talbot Rice, whose loosely McLuhanite proposition is that the mind exists outside of our brains, but is also inherent in our bodies and the world outside us, including the tools and technologies we use, and the ‘techniques we might use to orient our understanding of ourselves’. Twelve artists articulate this broad position, from Gianfranco Baruchello to Daria Martin, Angelo Plessas to Magali Reus; we can expect everything from shadow puppetry of extinct animals, to robots that learn through contact, to excursuses on ‘the impact of electromagnetic waves on our thoughts and cultures’.

Performa 19 at various venues, New York, through 24 November

The aforementioned Atkins is branching out into theatre as part of Performa 19, which makes sense given the wordiness of his previous video work (and his writerly tendencies generally). He’s not the only artist in the long-running New York City-wide performance festival – which this year looks back to the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus to put a stress on interdisciplinary practice – to be spreading his wings. Among the other early announcements of commissions is one by Nairy Baghramian, mixing her interests in dance and theatre with a focus on how the body accommodates itself to architecture, everyday objects and ‘gendered roles in domestic spaces’; a musical by Korakrit Arunanondchai based on Ghost Cinema, a collective postwar ritual in Vietnam involving outdoor screenings that serve as a conduit between the earthly and spirit worlds (we’re looking forward to seeing how that plays out); and another musical by Samson Young that looks set to mash up Chinese folk myth, comic books, Balanchine and Stravinsky. Really.

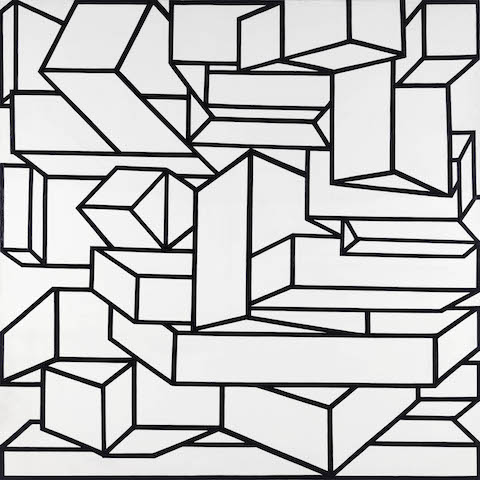

Al Held at White Cube, Hong Kong, through 4 January

Al Held was a boss of hard-edge painting, his work moving from seriocomic geometry in the 1960s – Red Gull, from 1964, looks like both what its title partly describes – a red gull moving through a blue sky with a yellow sun behind it – and a Pop-flavoured closeup of a superhero’s costume. B/W V from 1967–68 predates Michael Craig-Martin with its thick black outlines of a tumble of stacked boxes. Held broke away from Greenbergian formalism and obsessive flatness – he was fascinated by Renaissance volumetrics – and his later works up to his death in 2005 feel at once like serious, intricately composed, brightly coloured systems of interlocking forms, artists’ impressions of fairground rides and high-end sci-fi book covers. Either way, they’re a lot of fun to look at; if you’re in Hong Kong, Modern Maverick begs for a detour. The fact that this writer recently made a lame ‘Al Held broke loose’ joke on social media shouldn’t keep you from taking the American artist seriously, though how you should approach its author is another matter entirely.

From the November 2019 issue of ArtReview