Superflex, Tate Modern, London, 3 October – 2 April

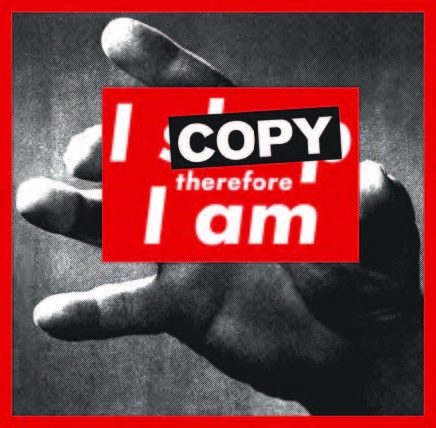

Since their formation in 1993, Danish collective Superflex have, among other exploits, set up a manure-driven biogas system in Tanzania (Supergas, 1997); collaborated with Brazilian farmers to create a sustainable, caffeine-rich soft drink (Guaraná Power, 2003); opened Copyshop (2005–), which queried copyright by offering various types of knockoff under the rubric of art and morphed into several other projects; and tried to get Palestine entered into the Eurovision Song Contest (Palestinian Eurovision, 2008). In 2010 they also did a deal with ArtReview: for a year, we agreed never to mention them by name; we failed (with a little help from our err… friends), with the result that Superflex took control of the features section of an issue two years later, in May 2012. Generally angling themselves towards exposing economic conditions and redistributing the means of production – even if it means legal trouble – Superflex are now the latest recipients of Tate Modern’s Hyundai Commission. Of course the artists are likely to do something new with the Turbine Hall’s vast, reverberant acreage, and as is traditional, Tate and they are keeping totally shtum. If Superflex did feel like revisiting an earlier work, though, we’d be fine with it being the open-source intoxicant they developed with a group of University of Copenhagen students in 2004 (and later expanded into workshops), the peerlessly titled Free Beer.

John Russell, DOGGO (still), 2017, video, 45 min. Courtesy the artist and Kunsthalle Zürich

John Russell, Kunsthalle Zürich, through 12 November

Also riding high in the appellation stakes is John Russell’s DOGGO, a word that, as the Twitter-habitu. English artist doubtless knows, is Internet slang for dog (see also ‘pupper’) but also means to lie low. And since Russell, as a member of gadfly anti-YBA grouping BANK during the 1990s, has previously put together shows entitled Fuck Off and Cocaine Orgasm, maybe this is him lying low. Then again, his solo work since 2000 has been powered by fearlessly in-your-face ugliness and overkill, particularly his trademark computer-generated sci-fi ‘rendered paintings’, where unicorns and purple tentacles sport against fuchsia skies, and daunting books such as the 800-page textual compendium Frozen Tears (2003) and equally sprawling Frozen Tears II a year later. Underlying all of it, seemingly, is a desire to skirt capture by market forces or interpretative ones. The show at Kunsthalle Zürich, featuring six ‘paintings’, nine sculptures, drawings and a feature-length film, is, we’re told, ‘not against or for something, it is not symbolic or realistic, it is not cynical, ironic or serious, it is not painting or sculpture… Whatever words you will choose to describe his works, they are the opposite as well.’ On reflection, we have nothing to add.

Juliette Blightman, Galerie Fons Welters, Amsterdam, through 21 October

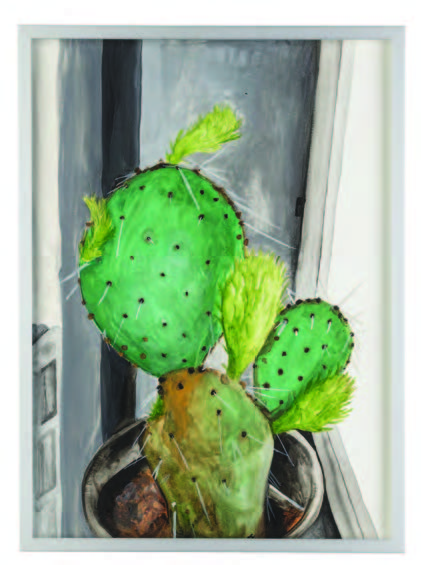

Genuinely lying low, though, is Juliette Blightman. Rewind a few years, and a typical work of the Berlin-based British artist’s would be a pot plant and a film projection of very little happening somewhere indoors, mostly static camerawork, the projector only being very occasionally switched on, giving rhythm and pattern to the gallery’s own timeframe. Blightman locates something weighty in quietude, in nothing moments; isolating them, she gives midafternoon doldrums scale and even something like force, repudiating contemporary art’s ambient pressure to assay grand themes. (Her use of live plants surely tracks back, via time she spent as Cerith Wyn Evans’s assistant during the mid-2000s, to Marcel Broodthaers, another artist interested in refusal.) Latterly, while continuing to make films, she’s established a flexible, hybrid format, interleaving occasional text paintings, canvases and drawings that tend to gravitate to, again, where the action isn’t: an unassuming tree, someone’s back, domestic interiors, swimming baths – and, as if establishing that the absolutely normal can still transgress, not a few penises.

Lyon Biennale, various venues, Lyon, through 7 January

Since its inauguration in 1991 the Lyon Biennale has been one of the more dependable of its kind, afflicted neither by gigantism or curatorial ego, vectoring manageably from a converted sugar factory on the city’s docks. Last time it was Ralph Rugoff’s turn at the curatorial bat, his La vie moderne considering the current status of the modern. Now Pompidou-Metz director Emma Lavigne picks up the thematic baton, this being the second part of a trilogy of Lyon Biennales on the subject of the modern, brainchild of biennale director Thierry Raspail. So Lavigne’s Floating Worlds again asks what modernity means today, interpreting it – via Baudelaire and, the title suggests, Ukiyo-e, but facing the volatile present – as a kind of transience, liquidity, randomness, unfolding. In any case, expect flesh to be put on those bones by a mix of old art and new: David Tudor’s 1968 walkthrough sound sculpture Rainforest, glimpses of the continuum of Tropical Modernism via Lygia Pape, Cildo Meireles, Ernesto Neto and Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, Shimabuku’s kites, Fontana’s slashes and contributions from younger artists including Jorinde Voigt, Ari Benjamin Meyers – themselves both focusing on the auditory – and Pratchaya Phinthong.

Rivane Neuenschwander, Infancy and History (WAR) (detail), 2017, 43 hand-sewn flags, 67 × 42 cm (each). © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Rivane Neuenschwander, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, 3 October – 4 November

Also among the artists here is Rivane Neuenschwander, who has long used fragile materials, chance processes and vibrant colour in an exploration of distribution that updates Latin American Conceptualism, particularly the circulatory, participatory art of Meireles and Hélio Oiticica: takeaway postcards, ribbons printed with wishes and little models made from straws by bored barflies, collected after hours. In Lyon she revisits A Watchword, a work begun in 2012 following protests (the so-called Bus Rebellion) in Brazil, when she started scouring the Internet for words related to protest and printing them on labels. These are pinned on bulletin boards: visitors are invited to take one and sew it onto their clothing, a conversation piece of sorts, making language and sentiment unpredictably mobile. Meanwhile, mobile herself, she’s opening her fifth exhibition at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London, where we can expect ‘new site-specific installations, projections and paintings’. In 2015 another artist represented by Friedman, Paul McDevitt, opened the art/sound project space Farbvision in his Prenzlauer Berg live/work space (having discovered, while renovating, a preserved tile-covered butcher’s shop under what had been a TV retailer). Apparently not daunted by the fact that he already runs a record label, Infinite Greyscale, with fellow artist Cornelius Quabeck, he kept the tiles and commenced an exhibition programme. The modestly scaled shopfront has since bloomed into one of Berlin’s more idiosyncratic venues, where artists and musicians you’d expect in bigger spaces – Paul Housley, electronica act Mouse on Mars’s Jan St Werner, Annika Ström, Stereolab’s Laetitia Sadier – are framed by retro ceramic walls and a general air of informality.

Caroline Achaintre, Farbvision, Berlin, 6 October – 11 November

The latest incumbent is Caroline Achaintre. One might broadly anticipate what the French/German artist will do – she works, as is widely known, between tufty, trailing, wall-based textiles, ceramics and drawings, her art hovering on the edge of eerie figuration, infused with theatricality, and melding all kinds of influences, from modernist design to German Expressionism – but you won’t have seen it anywhere like this.

Condemned To Be Modern, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, through 28 January

To return to Latin America and the continuing modern (which, despite what Bruno Latour said, isn’t going anywhere), over in Los Angeles is Condemned To Be Modern at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, part of Pacific Standard Time but worth considering in isolation. It brings together 21 artists from the past two decades ‘who have responded critically to the history of modernist architecture in Latin America’: here, figures including Jonathas de Andrade, Leonor Antunes, Renata Lucas and Melanie Smith look at the imposition of modernising processes and ideologies through the prism of buildings (new government buildings, public housing, universities and even, as in Brasilia, entire cities) in Brazil, Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela and elsewhere.

Pascal Hachem, The Mosaic Rooms, London, through 2 December

Pascal Hachem’s show at The Mosaic Rooms, the nonprofit showcase (in London’s Kensington) for art from the Arab world, comes wrapped in what might seem at first blush like a glib, paradoxical, even non-title, The show has a long title that I don’t recall anymore. But there’s a pointed intent: the Lebanese artist wants to get at how the past can be held onto in his hometown of Beirut, which has frequently been a city of fragmentation and change. Via a series of mechanised, readymade-based installations, Hachem – who’s in his late thirties and has also founded a design studio, 200grs – appears to be brusquely poeticising that condition. Trousers are suspended above mirrors, a stone where one foot should be, the weighted clothing striking the glass at intervals until it breaks. Elsewhere, wire brushes scrape the wall, revealing earlier layers of paint, and two irons tirelessly flatten a pile of flour, creating a fragile evenness – all of which, the organisers reckon, ‘hints at the impossibility of grasping meaning in the face of successive events’.

Mircea Cantor, Fondazione Giuliani, Rome, 13 October – 16 December

Mircea Cantor makes videos and sculptures that are heavy with allegorical import, and have been diversely interpreted, though they’re often centred – it seems – around the necessity of investiture in the present moment. (Cantor is Romanian, but there’s no way that his work is going to be reduced to that country’s difficult history.) In the three-hour Deeparture (2005), a video for which he placed a wolf and a deer together in a gallery, one might correctly assume that there isn’t a bloodbath, just a tautly stretched condition of anticipation and a reservoir of potential metaphor. In Tracking Happiness (2009), a group of women standing on sand constantly sweep away each other’s footsteps; this, for Cantor, relates to the idea that you can’t follow someone else’s path to find your own happiness. Vertical Attempt (2009), a one-second video featuring a child ‘cutting’ a flow of water with scissors, is endlessly looped, a Sisyphean act in which, nevertheless, the ‘attempt’ registers as optimistic. Cantor has said he’s interested in a condition of suspension because it’s ‘a place to speak about new possibilities’, whereas finishing something doesn’t necessarily bring about anything new. At Fondazione Giuliani, he wraps his show in a characteristically hopeful title: Your Ruins Are My Flag.

Helen Rae, White Columns, New York, through 21 October

New York’s White Columns, particularly since expat Mancunian Matthew Higgs assumed command in 2004 and shifted the venue’s narrative away from emerging artists, has a long history of presenting artists overlooked by the mainstream artworld – not least those with developmental or mental disabilities. In the case of Helen Rae, though, the seventy seven-year-old artist has already – just – become a known property. Rae, who’s lived in Claremont, California, all her life, was born deaf and is nonverbal, and learned to draw three decades or so ago at First Street Gallery, a local support programme. She’s lately had a couple of shows, and some art-fair presentations, of her vivid, fashion magazine-inspired paintings – defined by evocative figural distortions – and has been profiled, aptly enough, in Vogue. One might easily forget the backstory, though. Rae’s paintings hew close to the original photos of dressed-up models in colour and form, but bend away from them in ways that feel profound yet ambiguous, limning all manner of uneasy new emotions on the models’ faces. If this is outsider art, the stress is on the second word, not the first.

From the October 2017 issue of ArtReview