Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, 8 June – 10 September 2017

There are black bodies everywhere in filmmaker Arthur Jafa’s exhibition-installation – bodies that are, on one hand, the objects of violence, and on the other the subjects of aesthetic performance. Jafa, whose recent rise to attention in contemporary art follows a long career in independent film, here presents a ‘mix’ of his own work with that of other artists, including Frida Orupabo and Ming Smith; an installation that is as much a theoretical statement of Jafa’s inquiry into what might constitute a ‘black aesthetic’ as it is a retort to the politics of race in America. A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions, then, shuttles between the celebration of black culture in the material form of the performing body, and the political character of being turned into an object by others: as Jafa put it in a conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, ‘I think Black Americans, in particular, are preoccupied with things, because when we came here we were things. We weren’t people. We weren’t human beings. We were things of a very particular sort.’

Refusing to become an object of others is a motif of the show. Jafa’s lauded 2016 video Love is the Message, the Message is Death is absent, but the visual conflict the work sets up – sequences of black people subjected to official violence, shot and forced to the ground by police, and water-cannoned in riots contrast with the physical gesture of falling and reclaiming balance, witnessed in the ecstasy of black gospel culture as much as in hip-hop – is unpacked in much of what is presented here. So the visitor is greeted with a wall-size reproduction of a press photograph of the Marin County courthouse hostage siege, where on 7 August 1970 Jonathan Jackson, younger brother of activist George Jackson, took hostage a judge and others in an attempt to free three black inmates of Soledad State Prison, following a week of racially motivated violence by white prison officers. Gun-toting, young, nervous, Jackson appears as the embodiment of the angry demand of black Americans to be recognised as more than things.

Ghosts of the political past haunt Jafa’s show. A large Confederate flag, dyed black, hangs ominously to one side – behind it, a smaller, similarly blackened Stars and Stripes hangs pathetically. A nearby photograph shows a group of black schoolchildren in segregation-era Virginia saluting the flag of the Union, suggesting complicity. In the context of the recent Charlottesville protests, the blunt implication is that this history still looms over the present.

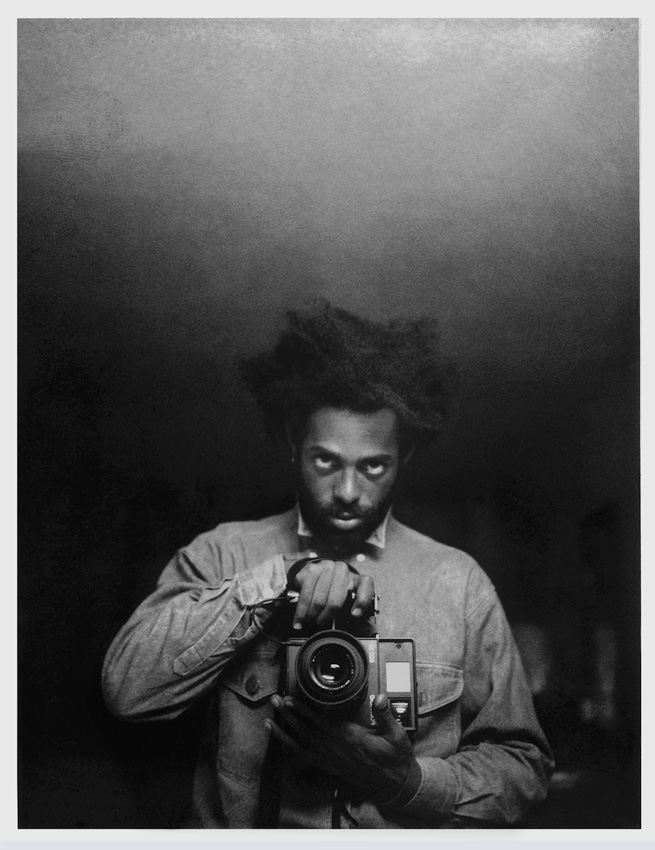

But as the historical focus of the show shifts, political violence and anger towards it unravels into something more ambivalent, more individuated, performative, frustrated. A standup cutout image of the Incredible Hulk, his green skin colour drained to black, pounds his fists furiously into his little bit of earth (LeRage, 2017). He’s the monster he doesn’t want to be – a trope Jafa recalls in his own ironic self-portrait-to-camera Monster (1989). A different kind of monster is present in the photo-collages of Orupabo, female figures formed from pinned-together fragments of what might be colonial ethnographic subjects, poised between subjection and self-invention.

Self-invention becomes a counter to objectification: on projection screens slanting across opposite corners of the circuit of rooms that make up the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, Jafa’s ‘mixes’ of video clips are running: we catch Jimi Hendrix in full flow at Woodstock; a sequence from the US TV dance show Soul Train, hugely popular with black American audiences during the 1970s and 80s; Parliament-Funkadelic’s Bootsy Collins, dressed in a spandex starman outfit, playfully teasing his audience that he’s going to make them come. Performance is escape.

Monster, however, throws down another challenge of Jafa’s aesthetics, that of the ‘objectifying’ power of the camera. You might take or leave Jafa’s rumination that ‘if you point a camera at a Black person, on a psychoanalytic level it functions as a White gaze’ – ‘the gaze’ is an overcirculated trope of contemporary theory – but here it leads the show to the work of photographer Ming Smith. Her photography of the 1970s and 80s, of black musicians onstage, of ordinary people in Harlem and elsewhere, throws out every convention of photo-documentary: low-light, motion-blurred yet not out of focus, Smith’s virtuoso looseness creates an atmospheric sense of place and intimacy, conjured by her rejection of the camera’s intrusive scrutiny.

Smith’s more sociable and societal vision, however, is hemmed in by Jafa’s narrower, almost existential attention to the body’s materiality. Along one wall, a shelf of ring binders stuffed with pages culled from magazines and books are the product of Jafa’s decades-long compiling of a kind of visual lexicon of a historical, diasporic blackness and a contrasting whiteness – fashion photography, celebrities, images from superhero magazines, contemporary architecture and design, ethnographic imagery, cosmetic surgery, tattoos, heavy-metal iconography alongside hip hop alongside traditional African art alongside insiderish contemporary art.

This relentless focus on the body and its performance seems paradoxically to essentialise blackness, draining away the historical contingencies of race. Maybe there’s a pessimism here, that race cannot be transcended, that it will always be with us. In one of the middle rooms, though, a showreel of other films opens some space around these questions – Kahlil Joseph’s Wildcat (2013) offers an idealised vision of the residents of the all-black agricultural town of Grayson, Oklahoma, highlighting the rodeo, cowboy aesthetic, a brilliantly jarring dislocation of stereotypes. This, and an old documentary from the late 1960s, about the frustrations of poor black residents of Venice, California, contrasted with the complacent indifference of suburban middle-class whites, asserts that refusing to be an object means demanding social and economic power and identity, a dimension that Jafa’s aesthetic preoccupations struggle to embody.

Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death is on view at The Store Studios, 180 The Strand, London, through 10 December

From the October 2017 issue of ArtReview