Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 9 June – 27 July

Whereas contemporaries such as Richard Prince, or younger artists such as Wade Guyton, use printing techniques to grant their paintings access to imagery and information beyond the reach of postmodern abstraction, Christopher Wool’s fusions of printing and painting are distinguished by their hermeticism. This may be best illustrated where it would seem most contradicted. Published in conjunction with this exhibition are two books of black-and-white photographs of backwoods Americana (Road and Westtexaspsychosculpture, both 2017), picturing light-industrial detritus abandoned in storage lots, piles of old tyres, dirt tracks winding through wiry cottonwoods, a tornado looming on the horizon. They look out at the world, but something about the attention Wool pays to their tonal textures makes them seem more concerned with how they echo the patterning of his largely black-and-white abstract paintings than with documenting the badlands of Texas or upstate New York. They have no apparent investment in the histories, or even the myths, of the places they show. They are the residues of a process that limits itself to a perfectly judged surface.

Wool has always had the mysterious ability to convert this formalism into a statement of loss, the loss of meaning. The random-looking typographical signs printed onto a series of lithographs, a.k.a. (2016), are even less signifying than the words and phrases of his text paintings of the late 1980s; but even those – with their swaggering expletives and elliptical, situationist quotes – were more about language as a pretext for abstract painting than a conveyor of meaning. The gesture towards communication served to highlight the limitation of the sign to its signifier. This introversion can end up as the self-indulgence of l’art pour l’art, as here in a series of works on paper (all Untitled, 2016), in which an image of stains and drips is a reproduced ground for doodled lines and erasures of painting. Process for process’s sake, avowing its futility, is overridden by an indolent air of generating gratuitous but collectable variants.

this paucity of image material is able to generate grand, looming paintings of astonishing surface complexity

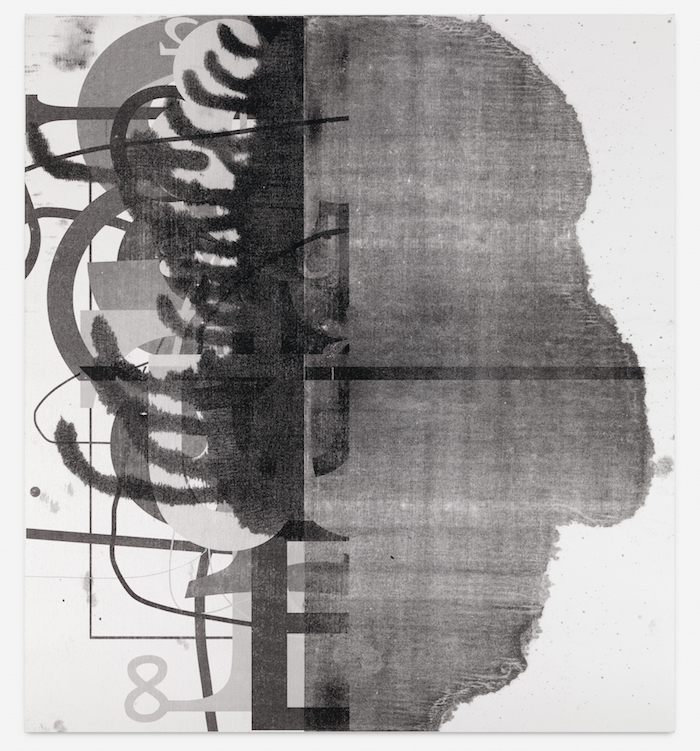

At best, however, in a series of five large paintings, each over 2.75 metres tall (all Untitled, 2016), Wool ekes grave drama out of phasing the image of painting into painting itself. Four silkscreen prints – images of paint spreading into an absorbent surface, to leave a curving, feathered edge – are applied to each canvas to form quarters of what resembles a large single blob of dark seepage. There is an ironic, Beckettian permutational logic – or illogic – at work in the shuffling, mirroring and inverting of these constituent prints to produce variations on these finely textured biomorphic shapes. One painting’s Rorschach image resembles a Darth Vader-ish mask. The broad dot-screen of the prints slips as it unevenly stencils the viscous enamel. Tautologically, these glitches are signs of an image becoming the kind of paint process it is at the same time picturing. The silkscreen’s radical enlargement of a relatively minute incident of facture leaves the silkscreens no detail on which their textures can be based. They are large shadows or silhouettes defaulting to the manual contingencies of the printing process for detail; but this paucity of image material is able to generate grand, looming paintings of astonishing surface complexity.

In Wool’s painstakingly extended exploration of painterly self-reflexivity – paintings made of prints of paintings made of prints, and so on, ad infinitum – the limitation to pattern and texture is a measure of the receding of the original in an ever more mediated world. The static of reproduction replaces the details of sources too insignificant to preserve: drips and stains less real than the paint reproducing them. In a new departure, Wool’s new silkscreen paintings transform this emphasis on pattern into the singularity of images monolithic as Easter Island head sculptures. Fragmentation gels into the focus of plot. The paintings resemble vast silhouettes, concealing an identity they massively hint at, as if however much you strive to make painting exclusively about itself it will end up being about you.

The last room contains another departure: a concrete sculpture on a plinth (Untitled, 2017). Teasingly figurelike, but not quite figurative, it narrowly withdraws from picturing the body that it powerfully intimates, and reverts to a statement of material and texture. But it is still out there, in real space, a radical defector from Wool’s consummately sealed pictorial world, tellingly unable to assume a legible form beyond its bounds.

From the October 2017 issue of ArtReview