Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York, 29 June – 18 August

What, if anything, of personal identity are minority and marginalised artists obligated to address in their work? This is the question that Elaine, Let’s Get the Hell Out of Here takes up. The show’s title refers to a remark once made by Joan Mitchell to her friend Elaine de Kooning, as recalled by the latter in 1971, in response to a male reveller’s address to them as ‘women artists’. The qualifier had clearly outstayed its welcome for Mitchell by that time in the mid-1960s, even as second-wave feminist artists around her began to push gender to the front and centre of their own work.

The pieces brought together for this exhibition, curated by Ashton Cooper, demonstrate subtler inflections of lived experience than those present in the identity-political artworks Mitchell would surely have disdained. Featuring 13 artists spanning the decades between Abstract Expressionism (represented by de Kooning and Mitchell as well as Grace Hartigan) and the present, Elaine… maps progressive attempts to grapple with identity by artists who alternately worked outside or slyly subverted the various signifiers of identity foregrounded in the works of their peers from 1960 onward.

Hartigan’s figurative oil Hollywood Interior (1993) is revelatory. A large canvas featuring a pink reclining silhouette with tasselled slippers, surrounded by two outlined women, one on the phone, the other apparently admiring her nails, this witty painting presages by 20 years the recent spate of graphic, tongue-in-cheek takes on the odalisque by young figurative painters such as Mira Dancy. De Kooning’s Edwin Denby (1960), meanwhile, is notable less for its insouciant sensibility than for its sitter. This oil on canvas, imposing and svelte at 2m tall and only 1.2m wide, depicts the elegant, whippet-thin poet and dance critic in a two-piece suit ever-so-slightly set o by a faint lavender halo echoing the hue of his fuchsia tie.

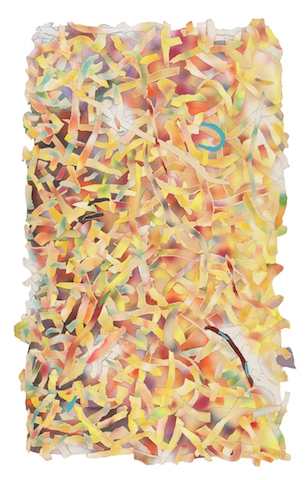

Al Loving’s Untitled (1976), made in the afterglow of the heyday of African-American abstraction, demonstrates an attempt to reconcile the artist’s increasing ambivalence regarding abstraction’s political efficacy with his abiding interest in abstract forms’ ability to captivate the eye. This vibrant paper collage, constructed from hundreds of multicolour squiggled strips, shows Loving’s departure from the hard-edge abstraction that had defined his early career. His use of humble collage brings modernist abstraction down to earth while pointedly stopping short of the direct address that defined many Black Arts Movement works.

Sheila Pepe takes a similar tack with her 2017 textile work On to the Hot Mess. A jury-rigged tangle of nautical towline, rope and shoelaces draped over the divider wall that separates the exhibition from the gallery’s street-facing windows, the piece continues the artist’s investigations into what she has frequently described as ‘hot mess formalism’, in which industrial and domestic fibres are repurposed in the service of dramatic ephemeral installations.

For all of its exemplary selections, the show sometimes seems to lose its conceptual footing by painting its inclusions with the same broad brush that the makers patently eschewed. After all, de Kooning’s decision to depict a gay acquaintance cannot be equated to Loving’s anxiety-borne embrace of collage. By bringing these works together under the auspices of the shared minority status of their makers, the show risks reinforcing the very labels Mitchell chafed against. Why remind the viewer of these labels at all? Because, one might reply, for better or for worse, they continue to inform both the production and reception of these and all artworks. By shining a spotlight on attempts, throughout the decades, to acknowledge personal identity without becoming engulfed by it, Elaine… inspires renewed respect for artists who persevere in full awareness of the uneven playing field.

From the October 2017 issue of ArtReview