Why Nauman? For anyone familiar with Bruce Nauman and his wellestablished place in the history of contemporary art, the answer, ‘Because it’s Bruce Nauman’, will suffice. But what will follow, inevitably, are explanations that, since at least the 1990s, have begun to harden into doxa: ‘No other artist has so consistently defied the pull of a recognisable style’. ‘No other artist’s practice has tarried more with incoherence.’ ‘No other artist has moved so effortlessly between sculpture, film, video, performance, photography, installation, etc.’ ‘No other artist has so antagonised his audience.’ ‘No other artist has such important devotees.’ ‘No other artist has managed in art what Beckett managed in literature and theatre.’ ‘No other artist is so tricky.’ ‘No other artist is a cowboy.’ ‘No other artist is smarter.’ ‘No other artist…’

None of these answer exactly ‘why Nauman?’ The artist, now in his seventies, is the subject of a third retrospective, his first in 20 years, and his second at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (though this one opened at the Schaulager in Basel in March). Both this exhibition and Nauman’s previous retrospective were organised by onetime MoMA deputy director and now Rauschenberg Foundation executive director Kathy Halbreich, one of Nauman’s devotees. For Halbreich, the persistence of ‘disappearance’ as ‘act, concept, perceptual probe, magical deceit, working method, and metaphor’ in Nauman’s art is what distinguishes, or at least organises, this year’s retrospective. While preparing her show, this ‘oxymoronic’ appearance of disappearance, Halbreich writes in her introductory essay to the catalogue, ‘surprised – really sideswiped me’, insofar as it offered a new means to understand Nauman’s notoriously difficult practice.

‘Disappearance’ is not Halbreich’s answer to the ‘why Nauman’ question, however. That answer is ‘freedom’. ‘Where freedom begins,’ she writes, ‘the absoluteness of truth disappears and becomes various.’ ‘Freedom demands canniness and care,’ she continues, ‘the developing of questions rather than acceptance of the often seductive deceits and prohibitions of authority. In encouraging the disappearance of certainty, Nauman may be the most political of artists after all.’

What is trauma except failure by another name – failure to represent, failure to incorporate, failure to work through and to sublimate?

One should read these words with great curiosity, because ‘politics’ is not something Nauman is known for. In fact, his ability to sidestep overt political content by bouncing around in the less well illuminated corners of the human psyche – his own psyche, really – is, if not a signature of Nauman’s work, then at least one of its more abiding tropes. If there is a politics to Nauman’s work, it is not one legislated by the work itself, but by the times that have received it. For what Halbreich encapsulates in her statements on freedom is not so much a new reading of Nauman as an evolution of the reception of his work over the years, a reception that can be broken into three main phases: its postminimalist reception from the 1960s and early 70s, the traumatic reception of the 90s and its contemporary reception – a political one – offered up as a new read, a new lease, on Nauman’s relevance today. That these phases only mark periods of Nauman’s reception is important to note, as the work itself does not periodise so easily.

The postminimalist reception of Nauman is the Nauman of process, performance and moving image. This is the Nauman of Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square (Square Dance) (1968) or Walk with Contraposto (1968), the artist’s iconic ‘studio’ works, in which, with only a 16mm film or video camera as audience, Nauman ‘did things’ in the studio, sensing that, at the moment when his peers, such as Robert Smithson, were leaving the studio to engage the dialectics of the outdoors, the studio was diminished – no longer sufficient, no longer necessary – and so open to new possibilities for practice, for actions taken without ends in sight. But this is also the moment of Nauman’s early fibreglass and polyester resin casts, works that were included in seminal exhibitions such as Lucy Lippard’s 1966 Eccentric Abstraction show, a catalogue of challenges to the orthodoxies of Modernism that still hung heavy over the art of that time. Nauman’s work of the 1960s was understood and received squarely within these terms, as work that engaged process, duration and the body, with all its weight and dimension, its presence and obdurateness, its ‘thrownness’ – all things that modernist art sought to sublimate and that Minimalism (as well as Conceptual art, and much Pop art too) sought to sidestep.

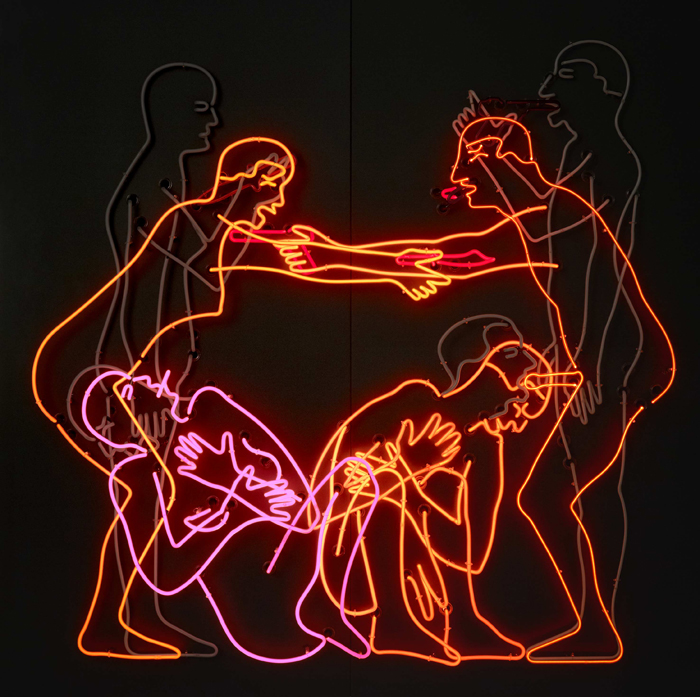

The Nauman of the 1990s, the traumatic Nauman, absorbs this postminimalist reception but expands it in order to make room for signs of subjective distress. This is the Nauman of psychic assault and battery, a vein that was tapped early with Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room (1968), whose disembodied voice creepily exhorts its audience to do just that. It reaches an apex with Clown Torture (1987) and Learned Helplessness in Rats (Rock and Roll Drummer) (1988), video installations in which the audience is again assaulted, but now by images of alien otherness (circus clowns, rats in a maze), subjected to harsh sounds (the torture victim’s pleas, rock ’n’ roll drums). Of the 1995 retrospective, in which most people encountered these works for the first time, art historian Pamela Lee noted that Nauman’s ‘almost hysterical proliferation of artistic procedures’ suggests nothing so much as his ‘inability to master the self’s relation to the world’. What is trauma except failure by another name – failure to represent, failure to incorporate, failure to work through and to sublimate?

The contemporary Nauman, the Nauman of 2018, might then be received as a champion of failure (the ‘pathos of failure’ is what Nauman’s work is about, according to Yve-Alain Bois et al’s Art Since 1900, 2004). If his strategies and aesthetic never seem to cohere, nor has his work achieved any clear meaning. The reason for that, at least according to Halbreich, is that ‘Nauman generously delegates responsibility for creating meaning to us’. The importance of this statement should not be tied to its veracity (recall, Halbreich holds that Nauman’s work disappears the validity of truth) but to the artists, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, for whom such a transfer of responsibility was a foundational condition of possibility for their art.

For Duchamp, the ‘creative act is not performed by the artist alone’, as it is the ‘spectator’ who, in ‘deciphering and interpreting [art’s] inner qualifications… adds his contribution to the creative act’, even when that act entails nothing more than pointing at something, anything, extant in the world. Nauman’s Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage) (2001), a multichannel video installation showing Nauman’s New Mexico studio at night and the very little (though not nothing) that goes on there, makes this lineage explicit. Like Cage’s ‘silence’, which is never nothing, so Nauman says this is my studio, my art. You be the judge of it. But you cannot deny it’s not nothing.

The question, then, is what kind of freedom is born of this doubled negative? A challenge to orthodoxy? A disappearance of certainty? A failure of meaning? And if these beget freedom, what kind of freedom is it? What politics attends to it?

We cannot afford, nor should we accept, a freedom that is predicated upon the ‘disappearance of certainty’ or that cashiers the ‘absoluteness of truth’.

Today, Nauman’s ‘pathos of failure’ has been domesticated by the tech industry, whose startup culture came to terms with its own anxieties by embracing the supposed benefits of creative self-destruction. The first FailCon, ‘a one-day conference for technology entrepreneurs, investors, developers, and designers to study their own and others’ failures’, took place nearly a decade ago. A common mantra around Silicon Valley, ‘Fail Fast, Fail Often’, was one of Stanford University’s most popular continuing education courses before it became a book, authored by Ryan Babineaux and John Krumboltz, in 2013. By the following year, New York magazine’s Kevin Roose had enough material to diagnose startup culture’s new ‘failure fetish’. The slackers had been absorbed by the Googleplex.

This would all have been quite amusing had not real politics in the US gone dark. In 2014 a new racial consciousness and street-level activism emerged in the wake of the deaths of Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner, in New York City, at the hands of the police. The following year, Ta-Nehisi Coates published Between the World and Me, a beautiful, and tragic, exposition of how American history is written on the backs, and in the blood, of black bodies. Then, in 2016, we the people of the United States elected Donald J. Trump to the presidency, and what has followed has been nothing less than a kind of moral bloodshed. Truth and facts – the cornerstones of certainty, and so of action and amelioration – have been massacred by venal foot soldiers for the politics of cynicism.

In 2018 we cannot afford, nor should we accept, the politics that Halbreich puts forward for Nauman. We cannot afford, nor should we accept, a freedom that is predicated upon the ‘disappearance of certainty’ or that cashiers the ‘absoluteness of truth’.

The artist, choreographer and conceptualist Ralph Lemon doesn’t. Writing in the same catalogue, Lemon addresses the politics of Nauman’s 1968 video Wall-Floor Positions:

‘Here was a particular projection of white-male autonomy taking place concurrently with the exigencies of the black civil rights movement, with this culturally defined lack of autonomy, creative and otherwise, and its resistance to organizational racism. (The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in ’65 – a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation.) I try to imagine a black body in an art studio, in the United States, in 1965, negotiating the inspired labor of positioning itself within the perfectly simple architectural confines of wall and floor. I cannot imagine it.’

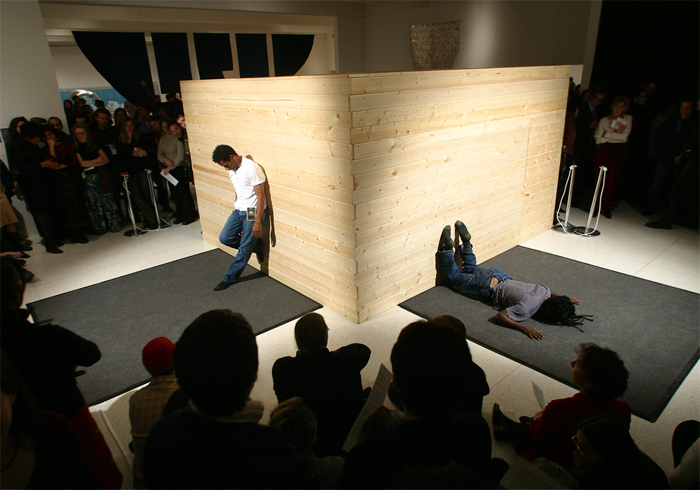

Lemon does not seem uncertain. In 2003, Lemon staged a performance of Nauman’s movement from Wall-Floor Positions before a live audience at the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis. There were two performers rather than just one, and both were black (one was Lemon). Two black bodies, alive, where once there had been only one white body, recorded.

Such an updating of Nauman’s work, an engaged and political reception of it, is generative of new certainties, of new absolute truths. It does point the finger of failure at Nauman, but as if to ask, rhetorically, ‘How could you have missed this?’ The answer to that question of course is freedom, the freedom that Nauman was privileged to enjoy in the 1960s as a young white artist, free to move about the country, and in this studio, as he wished. This freedom that was not, and is still not, shared by all. Nor is it a freedom that comes from a disappearance of certainty, but rather one that becomes explicit, one that appears, against the backdrop of its absence. This is called getting at, and down to, the truth. It’s also called enlightenment. If Nauman is relevant today, it’s because artists such as Ralph Lemon can make his work relevant, not just for us, or for Nauman himself, but for now.

Jonathan T.D. Neil is an associate editor of ArtReview. Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts is on view at MoMA and MoMA PS1, New York, 21 October – 25 February

From the October 2018 issue of ArtReview