6th Athens Biennale, Various venues, Athens, 26 October – 9 December

The 6th Athens Biennale is subtitled ANTI, and while one can think of numerous geographically and temporally specific reasons why, curators Stefanie Hessler (a regular ArtReview contributor), Kostis Stafylakis and Poka-Yio are evidently adopting a more meta and universal angle. Namely: how to be, or remain, oppositional in a post-truth era and at a moment when dissent is reflexively co-opted by the mainstream? (The all-caps ANTI, you may recall, was the title of Rihanna’s most recent album, which topped the US charts.) ‘To deal with ANTI means to oscillate between power and revolt by internalizing, reenacting or cannibalizing both,’ the organisers write. Which, aside from practical and budgetary concerns, may explain why the art is being set in everyday spaces both physical and virtual: a gym, office, tattoo studio, dating website, migration office, shopping mall, nightclub, etc. Populating these zones will be works, or projects, by more than 100 artists, ‘media creators’ and theorists, among them Monira Al Qadiri, Heather Phillipson, Jon Rafman, Eva Giannakopoulou, and Ryan Trecartin & Lizzie Fitch.

57th Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, 13 October – 25 March

In 1896, just before beginning to give away 90 percent of his huge fortune, steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie dreamed up a smart way of scouting new acquisitions for his Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, as well as educating the general public on contemporary art. This was the Carnegie International, the oldest survey of its kind in North America and just a whisker younger than the Venice Biennale (est 1895). Since then, the CI has seen some phases. Initially annual, it’s now triennial; for almost half its life it was focused exclusively on painting; it was once juried by Marcel Duchamp; and it has served as a platform for thousands of artists, including Salvador Dalí, Alberto Giacometti, René Magritte, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol. For the 57th edition, expect a pan-generational spread among the 32 included names and, avowedly, an emphasis on ‘international’, the roll-call ranging from El Anatsui to Alex Da Corte, Tacita Dean to Park McArthur, a collaboration between South Korean artist/filmmaker Im Heung-soon and Booker-winning novelist Han Kang, and a show-within-the-show, Dig Where You Stand, organised by Cameroonian curator Koyo Kouoh.

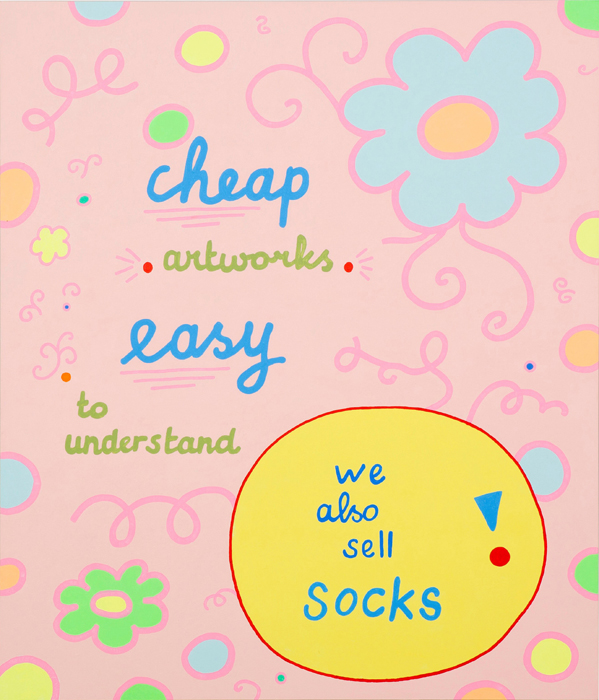

Knock Knock: Humour in Contemporary Art, South London Gallery, through 18 November

Every now and again a London art institution wonders aloud whether art can be funny. Cast your minds back to the Hayward Gallery’s 2008 show Laughing in a Foreign Language, and now cast them forward to the South London Gallery’s Knock Knock: Humour in Contemporary Art. When the former exhibition was launched, the global financial crisis had yet to happen; a decade later, the SLG reckons, we need cheering up – though they’re in a relatively buoyant mood anyway since this show spreads over both the main space and the gallery’s new three-storey annexe in a former fire station. Can art be funny? The artworld is self-serious enough that it maybe doesn’t take much to constitute light relief; but the list of artists here certainly skews to the authentically witty, from Maurizio Cattelan, Rodney Graham, Jayson Musson and Judith Hopf to Hardeep Pandhal, Bedwyr Williams and Amelie von Wulffen – plus, in a few cases, one-liner conceptualism that will probably feel uncommonly at home.

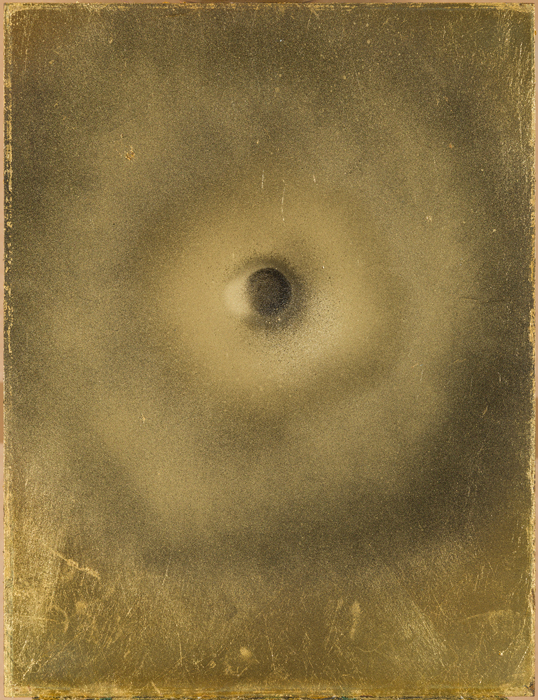

Black Hole: Art and Materiality from Informal to Invisible, GAMeC, Bergamo, 5 October – 6 January

In Bergamo, expect relatively scant laughs from Black Hole: Art and Materiality from Informal to Invisible, though the title is fair warning. The brainchild of new GAMeC’s director Lorenzo Giusti, and the first segment of a three-year, three-exhibition research project looking at the nature of matter, this is a very serious and ambitious show. It starts from the proposition that the twentieth-century popularisation of destabilising scientific theories such as Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and quantum mechanics made representing the world through art untenable. It also, though, underwrote the ‘informal’, deforming styles of Lucio Fontana, Antoni Tàpies, Alberto Burri et al, whose presence leads, here, to figures such as Urs Fischer and Cameron Jamie. The tripartite display goes on to consider the fundamental and universal nature of matter, of which even human nature – hazards Giusti – is composed, instrumentalising artists from Auguste Rodin and Medardo Rosso to the CoBrA painters and, somehow, up to young artists like Florence Peake. And the show closes out, as per the title, with explorations of the material but essentially invisible, including Jol Thomson’s collaborations with scientists over the tenuous nature of neutrinos and Hicham Berrada’s performances, ‘which invite the spectator to a direct experience of the energies and forces emerging from matter’.

Taro Izumi, White Rainbow, London, through 3 November

After that learning curve, let’s backslide into humour, albeit humour with serious intent. In his 2017 show at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, Taro Izumi set up intricate bric-a-brac models of initially uncertain function, positioned alongside diptych photographs: one side featured footballers at crucial moments in matches, the other Japanese kids plonked in Izumi’s constructions so that they replicated those moments, eg a striker in midair during a tackle. Izumi has suggested that part of the rationale behind these works was an imitative heroism, since Japanese football isn’t world-beating (due to short legs, he reckons), and this self-deflation is typical of his effusively cross-media work. In an early piece, 2006’s Lime at the Bottom of the Lake, viewers gazed into a cardboard structure to see him, on video, being squished by a giant hand. In 2010’s Untitled, meanwhile, four plywood walls each feature green fluid seeping from a hole in their centre, while video of the same paint in motion is projected onto and around it. At the core of Izumi’s art, you sense, may be a frustration with life lived through screens and an urgent need to reengage with physicality, a familiar enough subject that he energises with materialist wit.

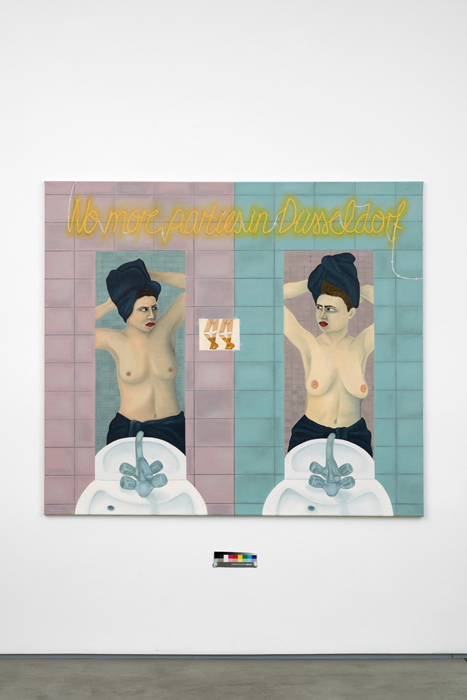

Katja Seib, Sadie Coles HQ, London, 14 November – 19 December

Two years out of the Kunstakademie in her hometown of Düsseldorf, where she studied under Tomma Abts, Katja Seib has a solo show at Sadie Coles HQ: not bad. She’s not an Abts acolyte either, unless you want to broadly consider painting as a site of spiralling, tightly designed complication. Seib paints warmly askew narratives, supposedly built on unrelated iPhone snaps (quite a few selfies, not always clothed), rooted in the real yet smartly estranged. In If not, not (2016), presumably created as her studies ended, Seib appears doubled in twin bathroom mirrors, hair bunched in a towel, one reflection glowering at the other while the Kanye West-referencing line ‘No more parties in Düsseldorf’ unfurls in golden neon across the tiles. Sub-images insinuate themselves postmodernist-style into her work, like the goofy animal drawing on the back of someone’s hand reaching into The Smell of Hollywood (2016), where Seib, or someone, gazes out of a floral-decorated room’s window at the Hollywood sign, arm cocked, as a baseball-capped youth manipulates her back and aqueous plants swirl in the foreground. On that, your guess is as good as ours, and – given that she’s apparently inspired by dreams – maybe as good as hers.

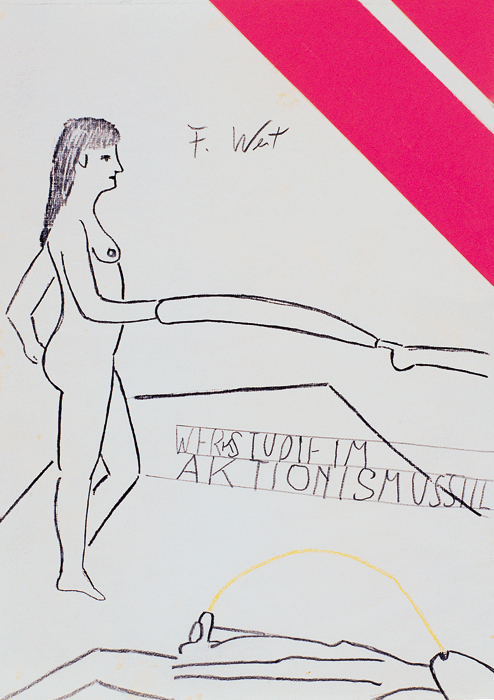

Franz West, Centre Pompidou, Paris, through 10 December

The largest-ever Franz West retrospective will almost certainly demonstrate that, in terms of contemporary sculptural aesthetics, we live in (tiny drumroll) Westworld. The Austrian artist’s lumpy, informal, pomposity-puncturing objects set the tone for a huge amount of recent art production; and his re-designation, via the Adaptives he began during the early 1970s, of sculpture as something to be picked up, played with, sat on or laid upon, was a genuinely game-changing move, refusing art as one-way transmission in favour of horizontality, mutuality, conversation. One imagines the conservators at the Pompidou (and Tate Modern, to where this show tours next year) aren’t delighted about letting audiences manhandle these artefacts, but without that you only have half the work. Here, conversely, six years after his death, and via some 200 works ranging from 1972 to 2012 – including rarely seen early drawings, papier-mâché sculptures from the 1980s, collages, models for outdoor works, furniture pieces and collaborations with artists such as Albert Oehlen and Heimo Zobernig – is West in all his punkish, egalitarian glory.

Pope.L, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, through 27 October

Now in his mid-sixties, and having latterly dropped the ‘William’ from his name, Pope.L is best known for performances, particularly his uncompromising and visceral endurance works: in 1990–91, for Eating the Wall Street Journal, he chewed up the titular financial paper while seated on the American flag; in The Great White Way (2001–09), one of numerous crawl-based pieces, he inched incrementally up the 35km length of Broadway wearing a Superman costume, a skateboard strapped to his back in lieu of a cape. Pope.L’s indictments of black disenfranchisement have lost none of their relevance, obviously. But the artist has also couched blackness and the body in diverse media outside his own frame, as One Thing After Another (Part Two) at Mitchell-Innes & Nash emphasises. Expect, among other things, a new version of the ongoing video project Syllogism, which mingles footage of Pope.L’s cat, the artist trying to balance a cream pie on his genitals and syllogistic statements such as ‘All men are pussies. Socrates is a man. Socrates is a pussy.’ Elsewhere, in what are described as ‘retro’ versions of earlier works, shallow acrylic boxes are filled with crumpled fertiliser bags, splatters of paint and images of Martin Luther King Jr. As so often with Pope.L, a staged collision of readings – here suggestions of growth and degradation concerning the avatar of civil rights – and structural refusal of the obvious nevertheless suggest a crawl through difficulty, towards fecundity, possibility, regrowth.

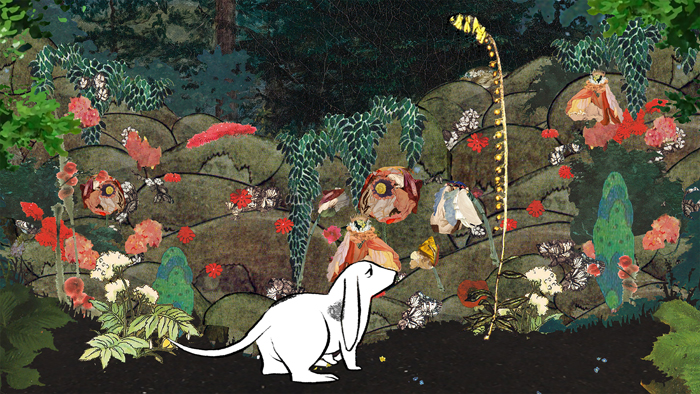

Metahaven, Stedeljik Museum, Amsterdam, 6 October – 24 February

The cultural convergence in which art becomes everything else and, in galleries and institutions, everything else becomes art has been undeniable for years; it’s a mixed bouquet. On one hand you’ve got, say, Metahaven, the consciously elusive, antiauthoritarian Dutch design-slash-art-slash-filmmaking collective (of apparently varying size, currently two) who, a decade into their career, are deservedly receiving their first survey show at the Stedeljik. The exhibition is split into five spaces, the first four showcasing the filmic works that the group have made since 2015 (and that haven’t been shown in the Netherlands before), the fifth compiling highlights of their design, textile and music video projects, presumably including their excellent work for/with experimental electronica auteur Holly Herndon. Premiering in the show, meanwhile, is Eurasia (Questions on Happiness) (2018), a mix of animation and documentary that folds together sci-fi, poetry and folklore and explores areas of the Southeastern Urals and Macedonia where belief trumps objective reality, a historical outlook that – as the show’s whole title, Earth, might indicate – feels to be coming for all of us.

Passageways: On Fashion’s Runway, Kunsthalle Bern, 13 October – 2 December

And then you’ve got projects like Passageways: On Fashion’s Runway. Organised by fashion curator Matthew Linde, it assembles some 30 runway videos and gussies them up in the language of art and cultural theory. The origins of the fashion show, we’re told, ‘reveal a constellation where the body, commerce and modernity converge… runways express the formaldehyde of a culture in flux… these runway experiments reconfigure the relations between audiences, arrangements of space, the carnivalesque body and the haunting of its commodity form,’ etc. We’re not saying they’re wrong. Alongside the runway videos, meanwhile, are original outfits by six of the fashion designers whose work appears in said videos, and a series of commissioned replicas. Which, of course, are not just replicas but objects that ‘rewrite histories of the runway as a suspension of fashion-time’. Duh.

From the October 2018 issue of ArtReview