This might be the month the United Kingdom finally leaves the European Union. Or – given the political chaos now engulfing the British political system, including a parliament in open war with a prime minister supposedly committed, ‘do or die’, to leaving on 31 October – it might not.

For many in the Remain camp, the choice by voters (predominantly in England) in the 2016 referendum to leave must have been motored by various forms of xenophobia, racism, ‘Little Englander’ mindset and a nostalgia for the bygone era of British imperial greatness. Whether one agrees with those views or not, there is little doubt that the three years since the Brexit vote have been marked by a renewed focus on the question of cultural ‘identity’ defined on national lines. Along with Donald Trump’s election as US president, Brexit is supposed to represent the rejection of a more cosmopolitan, multiculturalist outlook, as much as it might be a protest against two decades of neoliberal globalisation.

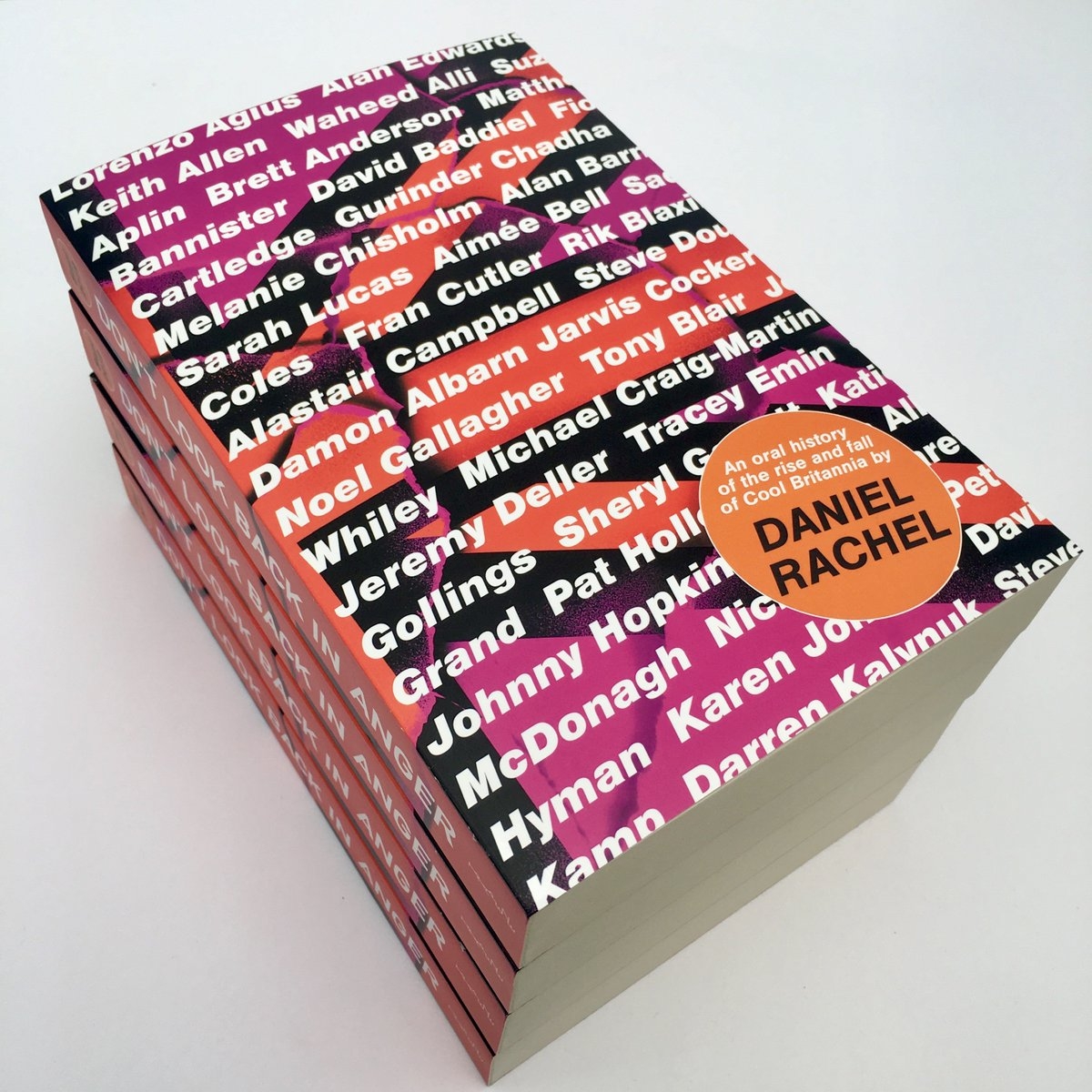

If the state we’re in now is a product of the society that emerged during the 1990s, the last time ‘Britishness’ and ‘Englishness’ became a vivid part of the cultural zeitgeist, it’s perhaps worth taking another look at that decade. Daniel Rachel’s Don’t Look Back in Anger – The rise and fall of Cool Britannia, told by those who were there does just that: it’s a remarkable compilation of interviews offering a vividly detailed chronicle of the extraordinary burst of cultural energy – across pop music, fashion, fiction, TV, film contemporary art and football – that characterised the 90s, from the perspective of some of the key artistic and political figures of the time. Damon Albarn, Noel Gallagher, Tracey Emin, Irvine Welsh and Tony Blair are just a few of the huge cast of Rachel’s subjects.

Rather than present each interview separately, Rachel intercuts his chorus of subjects according to particular moments or topics. It’s a sophisticated and useful literary device, and what emerges is a decade in ‘three acts’: the decrepit, Tory, recession-hit Britain of the late 80s and early 90s, and the catalysing, hedonistic experience of rave in youth culture; the aftermath of rave and emergence of broke-but-can-do creative people across fashion, art and music, and their growing success in the anarchic, drug-fuelled party atmosphere of mid-90s London, epitomised by ‘Britpop’; and the rapid deflation of the ‘Cool Britannia’ bubble after the election of Blair’s New Labour in 1997, via the death of Princess Diana and the global shock of the 9/11 attacks in 2001.

Britpop drives the narrative, but then it was the Britpop bands that were most vividly implicated in mining British cultural history, in their return to 60s-inflected guitar-pop. As Ocean Colour Scene frontman Simon Fowler puts it, ‘Maybe it’s an age thing. Everyone suddenly realised how exciting the sixties were. What would their relationship be with the sixties? Their parents’ record collection.’ That return to songmaking was also in reaction to the dominance of American pop: Suede’s Brett Anderson argues, in a swipe at Nirvana, that ‘if there was anything good that came out of Britpop and Cool Britannia, it was a rejection of American cultural imperialism’.

As many of the interviewees point out, the Union Jack-waving bit of Britpop was the media’s reductive take on these bands’ more ambiguous explorations. Albarn explains that Blur’s breakthrough albums, Modern Life Is Rubbish (1993) and Parklife (1994), were a ‘satirical look at the erosion of an Englishness and the emergence of a new mid-Atlantic, post-European weirdness’. But while it may have been ironic, that turn back to an older cultural iconography still resonated with a generation of listeners in their twenties. Don’t Look Back in Anger isn’t sociological analysis, it’s oral history, but the accounts highlight how cultural iconography and attitude were embedded in social class. Vulgarity, hedonism, bad taste, comedy, sex, drugs and drinking became the cultural vocabulary of the rejection of the repressive, censorious and hypocritical culture of Britain under Margaret Thatcher. As Emin cheerfully recalls of the merchandise she and Sarah Lucas made while running their collaborative ‘shop’, ‘I did a T-shirt that said “HAVE YOU WANKED OVER ME YET”. And Sarah’s T-shirt was “I’M SO FUCKY”. We were years ahead of Loaded magazine and laddism and ladettes.’ Or as Welsh succinctly puts it, ‘Margaret Thatcher was a lower-middle-class bigot who hated working-class plebs… She was an arsehole’.

Don’t Look Back in Anger evokes how Britpop, Young British Art, style-magazine culture, the ‘New Lad’ (and ‘Ladette’) culture and football culture celebrated hedonism and called back, past the Thatcher 80s, to a hazily remembered memory: of the last time youth culture was in the ascendant, tinged with nostalgic attachment to working-class culture. Though, as comedian Meera Syal and Cornershop’s Tjinder Singh rightly point out, it was inevitably a predominantly white culture that was being called back to. The celebratory mood of a ‘New Britain’ embedded in a renewed love of football and beer-drinking struck some as nothing more than a risky retreading of nationalistic jingoism.

But in truth, much of the harking-back to working-class attitudes and pre-Thatcher British culture was a kind of depoliticised eulogy for the destruction of working-class life during the 80s. Similarly, the revival of a distinctly British cultural iconography was less jingoistic nationalism than the surfacing anxiety among ‘Thatcher’s children’ that they didn’t really know what kind of country they now lived in. As a substitute for those destroyed solidarities, there was hedonism and drugs and – the worst innovation of the 90s – the fake togetherness of mass emotionalism, which crystallised in the public grief at the death of Diana. As Jeremy Deller points out, ‘It was a form of hysteria. People could express their own unhappiness with the world… and it became this self-generating thing.’

As the 90s became the 2000s, many gained from neoliberal economic globalisation, and nationalism – and the nation state – were no longer political in the way they had been. In the European Union that took shape in the 90s, European nation states became more integrated. The financial crash of 2008 threw a spanner into these works, and the dereliction of many English communities outside of the big cities – the same communities that were first wasted by deindustrialisation, and from which many young creatives left during the late 80s – has become critical. It was these regions where most voted to leave.

It’s hard to detect a major resurgence of ‘Little Englander’ cultural nationalism today. Ironically, many commentators forget that the twenty- and thirty-somethings of the 90s – the Britpop generation – are the forty- and fifty-somethings of today, a demographic that tended towards Leave in the referendum. In some sense, that generation is looking back in anger.

Don’t Look Back in Anger by Daniel Rachel, Trapeze, £20 (hardcover)

From the October 2019 issue of ArtReview