‘Everyone’s looking for Banksy,’ read the billboard besides the crossroads in Stuttgart. But I wasn’t looking for Banksy. I was looking for a drink. If I had been looking for the British artist, I wouldn’t have started in south Germany. Even in that case I would have been disappointed, because closer inspection of the small print beneath the poster’s bold claim –‘we have him!’ – revealed that the Staatsgalerie did not, on point of fact, have Banksy. It had a work by Banksy, called Love is in the Bin (2018), which it was displaying for a short time among its permanent collection.

I wasn’t looking for Banksy. I was looking for a drink

I walk past a Banksy every day (his homage to Jean-Michel Basquiat in a central London underpass). I’ve likely walked past many Banksys without noticing. I’ve likely walked past Banksy himself many times without noticing. This is not one of my life’s great regrets. Besides which, high on the list of reasons I was in Stuttgart was to get away from the British artworld, of which (given that his works now sell for millions and are shown at institutions like the Staatsgalerie) the street artist is, whether or not he or anyone else likes it, a part. Contrary to the poster’s assumptions, I was actively avoiding the possibility of bumping into either a or the Banksy.

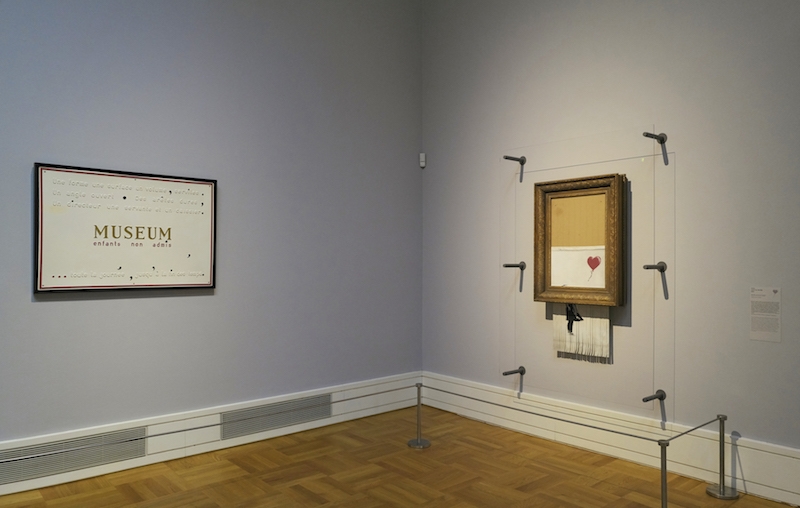

Nonetheless, my unswerving sense of professional duty meant that, the next day, I dragged my friend and my hangover to the museum. As predicted, the famously elusive artist was nowhere to be seen – unless he was disguised as the female invigilator overseeing Love is in the Bin (2018). The wall-hanging sculpture, as I guess it should be called, comprises a gilded frame in which is hidden the shredder that, during an auction last year at Sotheby’s, incompletely destroyed the stencilled drawing (Balloon Girl, 2002) that now dangles half-shredded from its bottom edge. That the only partial success of the operation meant that the original’s sale for £1m was not compromised (the buyer agreed to accept the remains as a new work) is its own story. Not to mention that its exhibition here (and what that entails for its resale value) colours a gesture that seemed to protest the commodification (and institutionalisation) of street art.

In my experience, the public is only invited into ‘discussion’ with works that the curators want semi-secretly to disavow

If the conflation of artist with artwork speaks of the museum’s desperation to capitalise on Banksy’s enviable name recognition (its less well publicised exhibition is by some nobody called Tiepolo), then its installation amidst a series of signs by Marcel Broodthaers speaks to the kind of ‘double-tracking’ that Rosanna Mclaughlin has recently identified as endemic in the artworld. The impression, to put it another way, is of the museum eating its cake while at the same time trying to keep it. A statement reassuring the visitor that Banksy’s temporary admission into the canon is intended to provoke ‘public debate’ is revealing, given that in my experience the public is only invited into ‘discussion’ with works that the curators want semi-secretly to disavow. I found no signs inviting me into discussion with the Tiepolos.

I’m all for the idea that art should be debated rather than dictated, but the specific placement seems less like a dialogue than a dog-whistle. Broodthaers’s playful sign works, which lampoon the ways that critical or commercial value is conferred on objects by artists and museums, might read to those familiar with the semiotics of conceptual art as a joke at the expense of the selfie-takers in front of the Banksy. Perhaps the intention was to elevate Banksy’s unashamedly literal work by placing it alongside one of the twentieth-century’s most brilliant and literate provocateurs, but it felt instead like an attempt to signal over the heads of its presumptive audience.

I admire [Banksy’s] ability to rile those who will accept even the most egregious tat as art if they encounter it in a polished white cube

The work will, it’s true, be moved around the collection, and so the Banksy ‘has to stand up to key works … from Rembrandt to Duchamp and from Holbein to Picasso’. This is patently counterproductive, presuming that the end is anything other than confusing the audience. If you stick Love is in the Bin next to a Holbein, it’s not going to make any sense. This is not (or not only) a question of relative artistic value: if you stick a Duchamp next to a Holbein then it is not going to make any sense, as a one-on-one relationship outside the field of four hundred years of art history, because the works speak different languages and at cross purposes. The museum might instead interrogate why the public is so captivated by an artist who speaks directly to his public and disrupts the established structures of power. Which seems, at this particular moment in European political history, like a discussion worth having.

I don’t have strong feelings about Banksy, though I admire his ability to rile people in the artworld who will nonetheless accept even the most egregious tat if they encounter it in a polished white cube. But using the artist’s popularity to lure unsuspecting visitors into the permanent collection, and to assume that all art speaks the same universal language, ignores that a meaning emerges not only in dialogue with the canonical history of visual art but, in Banksy’s case, with the subcultures of street art, political activism and underground music. To acknowledge as much is to take to heart the lesson of Broodthaers’s signs, namely that the museum is not the only space in which culture exists or in which conversations around culture can take place. The billboard poster promoting the exhibition, incidentally, had been tagged by a local street artist. There’s dialogue.

Online exclusive published on 27 November 2019