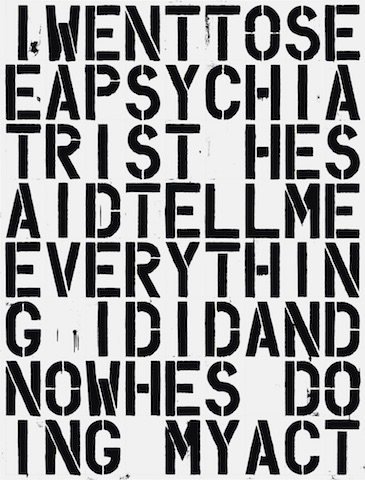

Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 18 September – 6 January

In the post-Watergate USA of the 1970s, cultural activity was inflected by a collapse of trust in governments and politicians, leading, in cinema for example, to a brief golden age for the conspiracy thriller. We can’t quite say – cough – why a comparable sense of disenchantment should exist right now, but look at the art museums, even the most august ones. At the Met, Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy collates a half-century of artists peering, as the institution gracefully summarises it, at the ‘hidden operations of power and the symbiotic suspicion between the government and its citizens’. Made between 1969 and 2016, the 70 works here – by 30 artists, including Hans Haacke, Cady Noland, Trevor Paglen, Raymond Pettibon, Sue Williams and Jim Shaw – trace an arc of diversifying world-weariness from JFK’s assassination to the recent past (eg 9/11), alternating between works that diagnose, uncover and intuit covert webs of power, and ones that ‘dive into the fever dreams of the disaffected’. That the show pointedly stops short of the last American presidential election and its aftermath is perhaps only to be expected. Then again, maybe the title says it all, and this is the Met’s way of quietly trolling the White House.

Black Light: Secret Traditions in Art Since the 1950s at Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, through 21 October

In Spain, Black Light: Secret Traditions in Art Since the 1950s approaches the clandestine from a less politicised angle, constructing an approximately chronological mixture of some 350 works that add up to a thesis on deceptive surfaces and hermetic content. That, and the curatorial need to periodically refresh the art we think we know. The show declares that canonical figures such as Antoni Tàpies, Barnett Newman and Agnes Martin, and other cross-generational luminaries such as William Burroughs, Joan Jonas, Francesco Clemente and Goshka Macuga, have all made work underscored by the notion of art as an entryway to higher cognitive planes, whether said artists are (or were) focused on abstraction, films, installations or whatever. Alchemy, psychedelics, mythology, Gurdjieff-style mysticism: such subtexts can apparently now be paraded without shame, releasing practices and artistic legacies previously mired in dull consensus. Aside from this, pondering why such magical and almost escapist thinking should be of current interest, writer/curator Enrique Juncosa points to, well, how the world is these days, and the fact that a lot of contemporary art is ‘rather boring’. Preach.

True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties at Max Hetzler, Berlin, 14 September – 27 October

And in this respect it’s no surprise when galleries take a backward glance. In True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties, selected externally by veteran Austrian curator Peter Pakesch, Max Hetzler’s Berlin gallery rewinds to the titular decade from the purportedly clearer, though perhaps also nostalgic, perspective of today. The archival work brought together here, by 37 Germans, Austrians and Americans, is situated in a temporal context between two flashpoints, 1968 and 1989 – the apex of the Cold War and its end, respectively –and as being made amid what’s described here as the liberating ‘end of the End of Art’, where artists stopped worrying about Modernism running out of road and either picked up paintbrushes or began addressing consumer society anew. In the process, Pakesch suggests, and between Cologne, New York, Los Angeles and Vienna, they wrung productive tension out of vouchsafing fervent individualism at a postmodern point where the individual as a concept was being undermined, at least by theorists. You can take all this on, or just browse a grouping that makes room for Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sherman, Mike Kelley, Albert Oehlen, Markus Oehlen, Martin Kippenberger et al, and also rewardingly elliptical figures such as Reinhard Mucha, Robert Gober, Liz Larner, Clegg & Guttmann and plenty more.

Gwangju Biennale, 7 September – 11 November

The 12th Gwangju Biennale may not be the first such event to reference ‘borders’, the subject being understandably everywhere these days. But it can claim some kind of precedence. The current subtitle, Imagined Borders, harkens back to the inaugural 1995 edition, Beyond the Borders – in the days when Borders was still a read-and-feed bookshop. In those days there was some expectation that globalisation, of which global biennials were a symptom, would undo borders. Yet here we are. (Meanwhile, Amazon undid Borders.) Art’s role now, the overseers reckon, is to move away from grand narratives and singular authorship and return to ‘the complexities of multiple voices and perspectives’. Here, its purpose is also to emphasise the artistic imaginary. Seven shows by individual curators (or groups of them) do that spadework, moving via 153 artists from 41 countries between everything from individual boundaries transgressed in daily life, to the constrained art of North Korea, to the history of the Gwangju Biennale itself.

Amy Sillman at Camden Arts Centre, London, 28 September – 6 January

Something simpler? How about a solo show by a painter. But then if we choose Amy Sillman’s first British institutional exhibition, straightforwardness is out. The Detroit-born artist’s 30 new works here will tour her knotty yet suave approach to painting, which synthesises postwar abstraction, sultry echoes of South-of-France Matisse, hints of psychedelia, fragments of figuration and a general sense of the bodily. But that’s not the complicated bit. Sillman is also materially heterodox, venturing out not only into printmaking but video animations and zines (her entire back catalogue of these, plus a takeaway new one, will be included here), and this show will additionally feature a site-specific, made-to-fit installation involving double-sided canvases. Similarly to Laura Owens, who also works in conversation with digital media and the prospects for painting it’s crowbarred open, Sillman is an artist whose fundamental inventiveness and verve make questions of the medium’s validity evaporate as you look. She’s also, gallingly, a very good critical writer. Go see.

Fiona Connor at 1301PE, Los Angeles, 8 September – 27 October

Fiona Connor similarly won’t be boxed in. The New Zealander, now in her mid-thirties and resident in Los Angeles for some years, has cofounded one gallery, made an art project out of converting her LA apartment into a project space and initiated a newspaper reading group as well as a loose collective that meets yearly in an old house in Northern Italy. Technically she’s an artist, but her artworks themselves often overlap with the real world, as in the series of meticulously recreated community noticeboards she showed at 1301PE in 2015. Noticeboards being, of course, something of a relic themselves these days. Her latest show at the same gallery is, we know, called Direct Address, and that’s currently all we know; but what’s clear about Connor, for all her dodging and weaving, is that she’s consistently focused on something the digital sphere is doing its best to make obsolete: real-world interactions between people, remaining in (what used to be called) meatspace in general, and all the unpredictable outcomes that can arise.

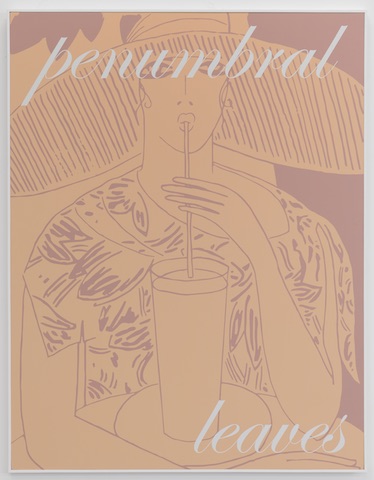

Marco Palmieri at Brand New Gallery, Milan, September – October

We were talking of Italy a moment ago; back there we go. Marco Palmieri, who studied in England but now lives in Rome, draws the iconography of his restrained paintings from package-holiday brochures and the bill of goods they aim to sell: palm trees, statues from antiquity, seashells, etc. On canvas, the classical and the leisurely are levelled as Palmieri reduces everything in his compositions to clean, wispy lines reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s pre-Pop illustration or old New Yorker cartoons, stranding his subject matter further out of time – he’s used the phrase ‘historical androgyny’ to suggest that an artwork can contain the essence of several eras at once. The result, faintly melancholic but also contagiously pleasurable, is like wandering through the vestiges of the Roman empire on a summer’s day.

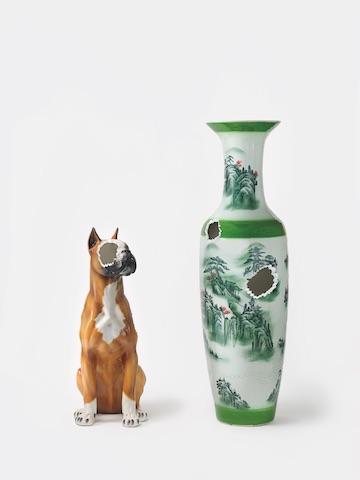

Nina Beier at Kunstforeningen GL Strand, Copenhagen, 15 September – 20 January

In her 2013 series Greens, Nina Beier pressed palm saplings flat so that they become, effectively, an image. This transition is characteristic of the Danish artist’s work, and so is the work’s controlled brutality. Here things are always shuttling, deliberately confusedly, between objecthood and representation. Beier has used human hair to make wigs that are, again, pressed flat and made imagelike, live material gone dead (she compares this to the process where peasant women would sell their hair to survive). She’s taken Chinese-made porcelain sculptures (of dogs, etc) and punched unlovely holes in them. She’s found stock images online, had them made into little sculptures and drowned them in resin-filled glassware. What the result means might be less important than all the things it could mean: ‘empty and open metaphors are created’, the artist said in a 2015 interview. But the outcome, as the ‘large coherent installation’ in this latest institutional show ought to reaffirm, is definitely an art of ingresses, where formerly fixed categories undo themselves and the viewer wanders, cued by a worldly ambience of violence, in the space between.

Marcel Broodthaers at Garage Museum, Moscow, 29 September – 3 February

And, finally, a third artist using palm trees: we didn’t plan this, but associations have a habit of arising from thin air, as Marcel Broodthaers well knew. It feels almost superfluous to recommend a retrospective by the Belgian poet/artist/filmmaker; though the fact that, 42 years after his death, it’s his first solo show in Russia feels notable. Broodthaers’s work, albeit in a delayed manner, shifted the axis of art production, particularly his undoing of museological categories in his sectional ‘conceptual museum’, Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles (1968) and his mutable Décors (1974–76), late-period proposals that created fragmentary narratives from pieces of his earlier work. Any cryptic assembly of objects adding up to something like a domestic space has some Broodthaers in it; so, really, does any artistic practice that moves fluidly between film, two-dimensional work and installation. (Though few are the artists nowadays who were poets until they were forty, and fewer still those who’d ceremonially ditch that practice by embedding 44 published volumes in plaster, as in Pense-Bête (Reminder), 1964.) If you want to wander through spaces you can’t quite trust, with language’s relation to the real world falling apart in front of you, go to Moscow.

From the September 2018 issue of ArtReview