Editor’s note: this article was first published in the September 2018 issue of ArtReview. It is republished here to coincide with Magic Ben Big Boy, a restaging of an exhibition held at Kiki, an artist-run space in San Francisco’s Mission District, and featuring works by Fecteau, Lutz Bacher and Nayland Blake. The show is on view at 526 West 22nd Street through 20 April 2019.

In the summer I visited Vincent Fecteau at his home in San Francisco, the city in which he’s spent his entire career as an artist. His walls feature works by B. Wurtz and Peter Saul, as well as an ecstatic finger-painting by a little-known local named Tomiko Ishiwatari. Fecteau serves as a volunteer art teacher at a long-term care facility and Ishiwatari had been one of his most enthusiastic students.

Fecteau takes pleasure in resisting the conventions of the professional art life – where he lives, what he looks at, how he thinks and when he works. Born in 1969 in the town of Islip on Long Island, New York, he majored in painting at Wesleyan University, in Connecticut, and then quickly walked away from two-dimensional media. Even now he doesn’t draw, not even as preparatory work. He says he prefers the tactility of sculpture and the slippery nature of the 360-degree object, which can’t fully be perceived from any single perspective. Fittingly, he spent several years working as a florist.

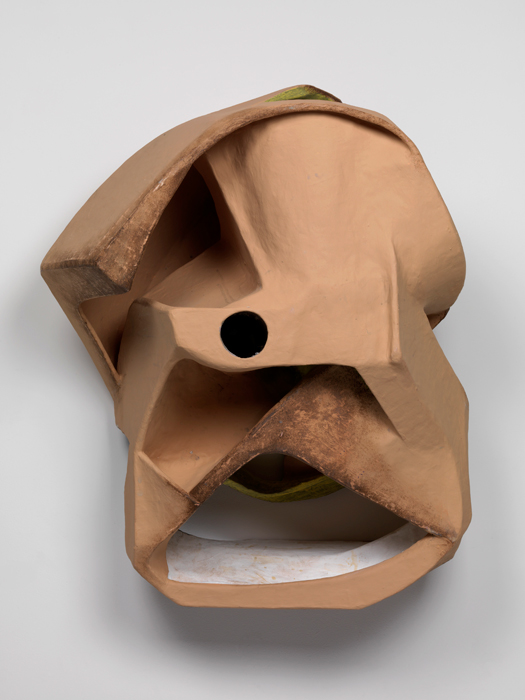

In the mid-1990s, when he began exhibiting, his work was primarily rooted in collage: small dioramas of haunted domestic interiors. Soon after, he developed his characteristic sculptures. These compact, evocative forms are built up slowly, in layers of papier-mâché, and painted in rich, matt colours. While his objects are relatively uniform in size and material, they can look alternately dense and fluid, architectural and corporeal.

In all his work, Fecteau embraces the impermanence of ordinary stuff and has maintained a remarkable consistency throughout his career. With humble materials – shoeboxes, found photos, wicker baskets – he makes the kind of bold, modernist gestures that are usually cast in heavy metals. While the work can appear austere, Fecteau’s process is torturous and emotionally draining. To maintain his sanity, he likes to keep his production level low: usually no more than eight works every 18 months.

Fecteau and I spoke in his studio, a bedroomsize space in the basement of his home. When I arrived, the room was tidy and bare, with two large worktables and little else. He had recently sent his newest body of work (dark, monochromatic, almost gothic sculptures) for a show at Greengrassi in London; but other than some drippings on the floor, there was no sign of art. This seemed to please him. “An empty studio”, he told me, “is the best time in the studio.”

ROSS SIMONINI Living in San Francisco, you’re separated from the mainstream artworld. Was that a choice?

VINCENT FECTEAU It wasn’t initially, but I don’t think I could live in New York now. Growing up on Long Island I always assumed I’d eventually live in Manhattan, but when I moved there for a summer, to intern for Hannah Wilke, I couldn’t handle it… It was just too much for me. Sometimes I even think this city is too much.

RS You came straight here from Wesleyan.

VF Yeah. I’ve lived here since 1991.

RS Do you have an art community here?

VF I do. There are a lot of great artists here.

RS It’s significant that you stayed in the Bay Area. Most artists can’t maintain a career here. They leave.

VF I was able to do it because I got early support from people outside of the Bay Area: Hudson [the founder of Feature Inc.] in New York and Cornelia Grassi in London. I have plenty of friends who have left, because it can be difficult to show outside of San Francisco if you live here. And it’s very difficult to have a sustaining ‘career’ if you don’t show outside of San Francisco.

RS The Bay Area creates singular artists – Bruce Conner, David Ireland, Lutz Bacher…

VF When I first moved here, I came to do AIDS activism with ACT UP. And then I realised why San Francisco was so appealing: it was a bit off the radar, which interested me, it was close to amazing natural beauty and it had a high tolerance for freaks and difference of all kinds. I worked for Nayland Blake for a while, but I wasn’t even sure I wanted to be an artist. Honestly, I’m still always looking for the thing that will be more suitable for me than being an artist.

RS Has anything come close?

VF For several years I’ve been volunteering with an art programme at a local hospital and rehabilitation centre in San Francisco, which I find very rewarding.

RS What would that job be?

VF I don’t know… psychiatric nurse? Or something like that. I had no idea I was interested in that kind of work until I started spending time at the centre. The art programme I work with is more about facilitating the making of work than teaching it. I’m really interested in art that needs to be made and the artists that, despite sometimes sizeable obstacles, make it. For some of these artists, there’s no bigger goal than creating. They may not care about the finished product or even think of these objects as art, but they are completely and totally engaged. I think for some people with compromised communication abilities it becomes their primary way of expressing their internal experience and engaging with the world around them. It’s inspiring.

RS Do you feel that way, making art?

VF Sometimes I do. But there’s so much outside noise that can get in the way when artmaking starts looking more like a career. I actually think the job of the artist is to try to protect the real or true creative act from all the other stuff.

RS: What’s the real part?

VF [long pause] I don’t know.

RS The thing you can’t talk about.

VF Yes. Maybe. I find it almost impossible to articulate. If I understood why, maybe I wouldn’t have to make anything. Sometimes I find it helpful to think of the work as simply evidence of an intention, or a desire, or an impulse. The end result is not that important. Maybe it’s that impulse that is the real or true part.

RS Does your process start with a feeling, or –

VF Always a feeling. I’m completely interested in one’s intuition and the unconscious. My experience of my mind is that it’s an incredibly chaotic place. Although the end result, the sculpture, is finite and very specific, that’s not my experience of the making of it. Which might be why I don’t really have strong attachments for pieces after they are finished. I don’t necessarily recognise them. That said, they must somehow always feel ‘true’ in the end. I’ve thrown away stuff even after working on it for months because it starts to feel false.

RS Do you throw away finished work?

VF No. If I show something, it is finished, and I accept it for what it is. It would feel dishonest to deny this thing that I once felt to be true. As embarrassing as it may be, it’s still true. Things don’t always turn out ‘great’, but that’s kind of irrelevant.

RS Greatness is a small sliver of the human experience. It would be a shame if that’s all art could depict.

VF I recently went to Amsterdam and saw the Van Gogh Museum for the first time. I was so inspired to see all the missteps and experiments, the complexity of this relatively short artistic life. Of course there are those amazing moments but also many things that were full of difficulty and struggle and even failure.

RS Have you ever shown work you thought was a failure at the time?

VF No. Not at the time. In hindsight, of course… but I’m way too self-conscious to do that. I know they’re not all perfect, but I believe they are good enough so as not to completely humiliate me.

RS Do you feel humiliated when you show?

VF Always.

RS Every show?

VF Yes.

RS Me too. I hoped it would go away.

VF I think it gets worse. For me, the desire to be recognised, to be seen, is inherently embarrassing. This last show was very painful. The work in the studio happens over a long period of time in almost complete privacy, and then all of a sudden it’s on public view. And I’m on public view! It’s shocking.

RS But it has to be done.

VF I fantasise about having a regular job, where I don’t have to obsess about what I do when I come home. It’s much less about ‘talent’ than having a drive or obsessiveness that won’t let up. It takes a real intensity. Every artist I know is intense.

RS And all this psychological noise is impossible for a nonartist to understand, probably.

VF There’s that scene in Close Encounters of the Third Kind when Richard Dreyfuss sculpts Devils Tower out of the mashed potatoes, and the wife and kids are looking at him, freaked out and crying. And he says something like, “I know Daddy’s been acting strange recently… I’m sorry… I can’t help it… It’s really important.” That scene really resonated with me. It’s the best description of being an artist that I’ve ever seen in a film. And that’s what it’s like: you’re doing a ridiculous thing, you don’t know why, but you have to.

RS Is your work dealing directly with that conflict?

VF Yes, I never really feel like I have a handle on the situation. I experience the process as flailing, searching blindly in the dark, hoping that something starts to make sense. When it does, it usually comes as a surprise, like it didn’t come from me… and then I know it’s finished.

RS It’s a funny idea, that an artwork has to feel alien to you. It has to be not you. You’d think artists would feel that the object should be a pure expression of their self, but it’s the opposite. It’s about erasing yourself.

VF In a way, but of course it’s still really you. You can run but you can’t hide.

I like the idea of the grand gesture that’s made with the humblest stuff

RS You’re working with vast, abstract ideas, and yet the materials you use are so modest.

VF Well, on the one hand, it’s just the mashed potatoes. You use what’s in front of you. And I like that these little things already exist in the world. I like the idea of the grand gesture that’s made with the humblest stuff.

RS It’s easy.

VF And it’s – relatively – easy. I’m not interested in fighting a medium. Some artists find meaning in the technical process. I don’t. It’s hard enough. I’m interested in why something is made more than how. The sculptures change constantly, sometimes almost violently, so I’m not really thinking about engineering or construction.

RS Has your work ever fallen apart after an exhibition?

VF No. I mean, the collage works are made with magazine pages, so those are light-sensitive, but the papier-mâché seems pretty stable.

RS Was collage your first work?

VF Yes. I was interested in all the references already packed into an art-directed image, and as a material it was readily available. But I think spatially, so although I started with collages, I was soon arranging them in space. I used foamcore because it was easy and cheap, and then when I wanted to make the forms larger and more complex I started using papier-mâché.

RS From the outside, there seems to be such a consistent development in your work through the years.

VF I don’t think about ‘development’. I don’t believe in the linearity of that kind of thinking. The thing I was looking for 25 years ago is the same thing I’m looking for now. In the end, I think we are relatively simple beings.

RS Do you think in terms of improvement?

VF I’ve tried to stop thinking in terms of good and bad when working. I’m convinced that the only relevant judgement to make is whether or not it’s true. I’m never going to get beyond my brain or my abilities. My job is to embrace that fact and dive in.

RS Are you are the same person you’ve always been?

VF I think my essential self is the same. One can change, of course, but I think what is at one’s core is consistent. A truth? A spirit, maybe?

RS Do you see older artists coming to a greater understanding of themselves in their work?

VF I’m not sure it’s an understanding as much as acceptance and maybe celebration. There’s a lot we can do with what we have. It’s a beautiful thing to embrace and celebrate one’s limitations.

RS Do you tend to like artists if you enjoy their work?

VF Not necessarily. There are definitely people whose work I liked but have been disappointed when I actually met them.

RS Does that seem like a contradiction, if the work is an expression of their interior?

VF Not really. There’s another step involved, which is that of the viewer. For the viewer, it’s all about them. What I respond to in a work might not have anything to do with what the artist thought they were doing. I think who the artist is becomes irrelevant at a certain point.

RS You mentioned the word ‘spirit’. Is art sacred to you?

VF I think about art and religion a lot. I think they are very similar. I’m very interested in what it means to have faith. I grew up Catholic, although I don’t consider myself religious in any typical sense. I think the problems with religion, like art, come from the institutions that are created around them. These institutions were established with the intent of protecting, but eventually end up compromising that very thing they were trying to protect. I think both faith and art are simultaneously, maybe paradoxically, incredibly fragile and resilient. And, ultimately, indestructible.

Ross Simonini is an artist and writer living in New York and California

From the September 2018 issue of ArtReview