It’s 29 December 1962. Britain is in the grip of that winter’s ‘Big Freeze’: heavy blizzards have swept the country and almost a metre of snow has fallen on Central London. Petar Ouvaliev, Bulgarian émigré and regular contributor to Art News and Review, is marrying his English fiancée, Sonia Joyce, at Chelsea Register Office. Getting there on time has become a problem. So Ouvaliev does what anyone else would and borrows Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor’s Rolls-Royce (with chauffeur). He’s been working on the production of the star couple’s film The V.I.P.s (1963), and as Joyce later recalled, ‘since [Burton and Taylor’s] “liquid lifestyle” meant they never awoke before the afternoon, he knew that the car and chauffeur would be back ready by the time they would need it’.

Ouvaliev, better known in Britain by his adopted name, Pierre Rouve, is on a roll. Ex-diplomat, art critic, broadcaster for the BBC World Service’s Bulgarian section, theatre director and lately film producer (having coproduced the 1960 hit The Millionairess with Peter Sellers and Sophia Loren), Rouve is the embodiment of the deracinated emigrant intellectual – urbane, cultured, polyglot, a consummate connection-maker. His life story is shaped by the forces of the Cold War. During the Second World War he serves in Bulgaria’s diplomatic service, finding himself in London as the land of his birth turned to communism and joined the Soviet Bloc. In December 1948 he abandons his post and applies for leave to remain in the UK, where he lives as a ‘stateless person’. To make ends meet, he starts writing for French and Italian art magazines. His sister, art-historian Dora Ouvaliev, lives in Paris, and has started filing reviews of the art in Paris for the new Art News and Review, which launches in February 1949. Soon, Rouve’s criticism is a mainstay of the publication, alongside writers such as Lawrence Alloway, Reyner Banham and David Sylvester.

As a critic he writes grandiloquent texts loaded with sweeping judgements on the shortcomings of contemporary art. Not far below the surface is a sensitivity to art’s historical migrations and the shifting geopolitical context of his time. Abstraction and figuration, for Rouve, are compromised by the political side-taking of East and West; in a 1953 review praising painter Prunella Clough he writes of ‘the social isolation imposed on modern art by what seems like a combined operation between the Kremlin and the Daily Mail on one side, and the artist’s hypertrophied egotism on the other’.

Born in 1915, he is one of the last generation of travelled, bourgeois European cosmopolitans, before Europe is split by the war and then the Iron Curtain. Rouve’s criticism is that of an Old World humanist, standing up for aesthetic wholeness in the face of a postwar world that he sees busily reducing human beings to cogs in a cybernetic machine. Unlike his contemporaries Banham and Alloway, he’s no technophile; in 1964, closing his report from the Ljubljana Print Biennial, in Eastern Bloc Yugoslavia, Rouve asks, ‘If man must not be a bundle of reflexes, why should he be a sum of mathematical equations? Between trances and computers where do we stand?’

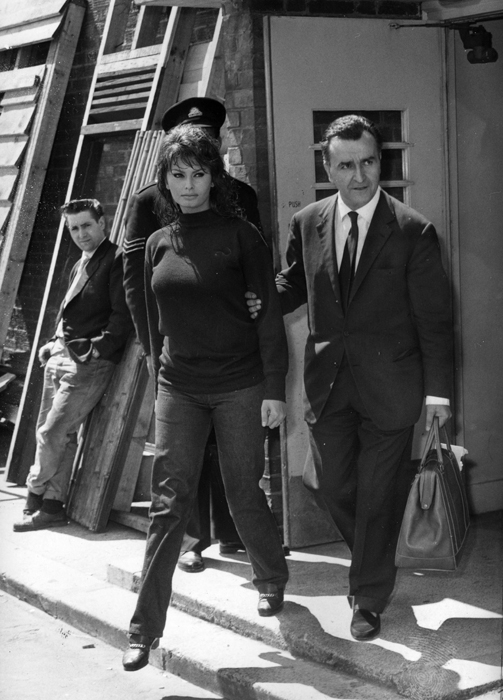

Also unlike writers such as Alloway and Banham, critical voices closely tied to the fortunes of contemporary art in the postwar, Rouve’s criticism is but one strand of his more eclectic, improvised, oddly glamourous trajectory through the 1950s and 60s, as he takes up whatever opportunities an entrepreneurial, stateless exile can find. His connection with Carlo Ponti, Loren’s husband (and an avid art collector), brings him his most important film credit – Rouve becomes executive producer on Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), the Italian director’s cryptic thriller about a fashion photographer in London at the height of the ‘swinging 60s’.

In a scene early on in Blow-Up, Thomas, the David Bailey-esque protagonist, takes a break from the shoot he’s working on to look in on his neighbour, a painter called Bill. Bill is a modern artist. He paints abstract paintings – canvases filled with fine dots, like sprayed paint. Bill is modelled on real-life English painter Ian Stephenson, and the paintings Bill shows Thomas in the movie are indeed by Stephenson, selected by Antonioni when he visited the artist at his studio before shooting for Blow-Up began. The connection is no doubt Rouve. A year or so earlier, Rouve has written a cover feature on Stephenson for The Arts Review (as the publication has been retitled) of 24 December 1964. There, he writes euphorically of Stephenson’s dissolution of form into colour and, ultimately, light: ‘Light veils and unveils. And Stephenson now paints this twofold movement of the invisible from which forms emerge… Colours coalesce in fragile configurations, forms fl utter in transient tensions. And our eye scans time.’

Rouve wants to put the viewer in control, at the centre of things. But it is Antonioni’s fictional Stephenson, Bill, who better captures the ambiguous, paranoid existentialism of 1966: “They don’t mean anything when I do them, just a mess,” he says to Thomas, explaining his paintings. “Afterwards I find something to hang on to… Then it sorts itself out, and adds up. It’s like finding a clue in a detective story.” Naturally Rouve was never far from the detective story himself. In 1970 he attempted to help Bulgarian dissident writer Georgi Markov find work in the British film industry, without success. On 7 September 1978 Markov was assassinated in London by an operative of the Bulgarian secret service (almost certainly with the assistance of the KGB), using a pellet of ricin fired from an umbrella.

From the September 2019 issue of ArtReview