‘Fuck the intention of the artist!’, read one of the slogans printed on Michel Majerus’s monumental skateboard ramp if we are dead, so it is (2000). In this light, some might think that scanning and reprinting the artist’s notebooks – and providing transcriptions in German and translations in English – rather misses the point. Many, however, will find the opportunity to read his mind irresistible, especially given that his life and artmaking were cut dramatically short by a plane crash, in 2002, when he was only thirty-five.

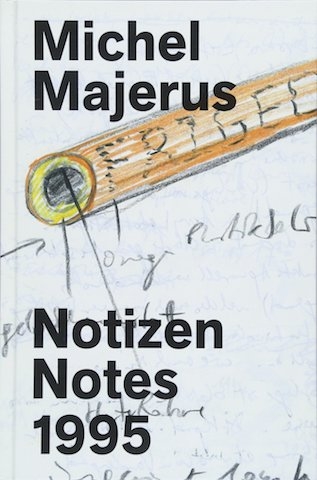

In 1995, having graduated from the arts academy in Stuttgart three years prior, the Luxembourg-born artist was living in Berlin and preparing for no less than five solo exhibitions, including his first ‘midcareer’ retrospective at Kunsthalle Basel. The three notebooks included here (out of 12 written that year, and published in conjunction with a three-part survey exhibition of his rarely shown early works organised by his estate) reveal an artist particularly self-conscious about his own production and place within art history, questioning both his role as a painter and the viewer’s relationship to his paintings, and incessantly comparing himself to the ‘dead suckers’ – a phrase he used for the artists he admired, both living and dead (George Condo, Georg Baselitz and Andy Warhol among them) – whose work he so often appropriated. As with his own work, where pop and youth culture merge with art-historical references, there is no hierarchy to the material included in his notes (it ranges from advertising slogans to grocery lists, from exhibition sketches to personal assignments – ‘analyze the extent to which a conceptual idea like the ones B. Nauman, Sol LeWitt… had, might be decisive for my development’), making for a frenetic read.

Majerus’s work, with its embrace of the self-evidence and ‘apparentness’ of contemporary visual culture, has often been cast as purely ‘intuitive’, editor Brigitte Franzen notes in an accompanying essay, and in challenging this consensus, the book is a valuable art-historical resource. As for these notes being an indispensable ‘key’ to ‘unlock[ing]’ his work, however, as Franzen later disconcertingly suggests (did it need unlocking?), this reviewer was filled with glee to find question marks punctuating the transcription, like last scribbled obstacles resisting interpretation.

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview