It’s a few weeks ago and I’m in the garden, perspiring, corkscrewing a posthole digger downward to bore a trio of one-metre holes for a row of fenceposts. Later there will be measured pours of sand and gravel, the ceremonial insertion of steel stakes, some angst involving a spirit level, cementing, a cold beer. But for now it’s basic grunt-work, and amid the periodic oaths, two things loop through this amateur handyman’s brain. Firstly the old saw, attributed to everyone from an anonymous Zen Buddhist to Tom Waits, that says ‘how you do anything is how you do everything’. Secondly, Bruce Nauman’s 1999 video Setting a Good Corner (Allegory and Metaphor), which happens to make the selfsame persuasive point before sailing beyond it.

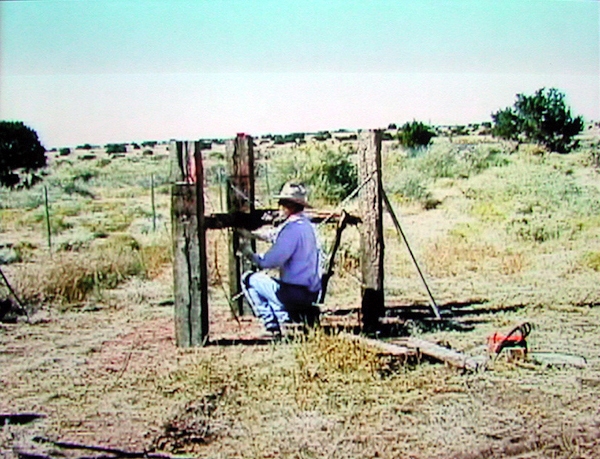

I think about Setting a Good Corner fairly regularly, whether doing something like this or not. Probably my favourite work by Nauman and one of my favourites by anyone, it exists for me, as most artworks do for most people, predominantly as a memory. I first saw it, start to end, in a museum group-show somewhere – those details have evaporated, no matter – suckered by its peacefulness and peculiarity and philosophic progression. Sometime later I saw it all again online; it’s subsequently been taken down. The video is 59 minutes 18 seconds long, one static shot without edits, and documents Nauman, in cowboy hat and workshirt and jeans, on his Las Madres ranch in New Mexico, essaying a tricky task: laying a triangular array of three wooden fenceposts in order to create, yes, a good corner. In a scrolling text at the beginning of the video, Nauman notes that you can’t have a good fence without a good corner. He’s using three-metre cedar railway sleepers as uprights, which have to be perfectly plumb or the whole structure won’t work, and he has carefully selected smooth rather than barbed wire to attach crossbeams, so that – as he writes – he doesn’t end up swearing on video.

The video begins in medias res, two posts already in, shafts sunk halfway into the ground, the earth tamped down. Over the course of the hour, Nauman – overseen by his neighbour and ranch partner, Bill Riggins – gets the third in. He has a similar digger to mine, but his is bright red (mine is black) and, because he’s smart, mechanised. He attaches wooden crossbeams and ties them tight, and finally hauls in a green gate. His wife, Susan Rothenberg, drifts in and out; so do several animals; it’s an ordinary day. At the end of the video there’s another scrolling text in which Riggins gets his neighbourly, comparatively professional say: Nauman did a decent job, he ought to keep his tools where he can find them, his chainsaw could use sharpening. (In a 2001 interview Nauman noted that he included the Riggins testimony because the latter had said, ‘Boy, you’re going to get a lot of criticism on that because people have a lot of different ways of doing those things’.) Then, since the video is on a continuous loop, the work starts over again – because that’s life.

That he subtitles said process ‘allegory and metaphor’ is a dust-dry joke – like you’d watch an artist laying a fencepost for an hour and not immediately, desperately think in terms of allegory and metaphor – but it’s also accurate

Setting a Good Corner is in Nauman’s long tradition of using a formal constraint. Here, everything is defined by the given activity: the video begins when this stretch of necessary and unglamorous work begins, and ends when it ends. That he subtitles said process ‘allegory and metaphor’ is a dust-dry joke – like you’d watch an artist laying a fencepost for an hour and not immediately, desperately think in terms of allegory and metaphor – but it’s also accurate. Upfront, Nauman is talking here about an art of living, of dailiness: patience, preparation, establishing a foundation, taking advice, thinking in stages, doing the (literally) boring stuff, over and over.

In his case, it also inevitably scans as recursive. The good corner he set, back in the 1960s, involved cornering himself in the studio. That work established singular concerns: a famously existential locus, a Beckettian rhythm of repetition that pivoted on itself because, in going round in circles (or walking in a square, or banging the back of his head against a wall), Nauman was getting somewhere vis-à-vis the human condition, living life as it is. From that foundation he went, of course, many other places: into sculpture, neon, holograms, photographs, sound, drawing, installation, printmaking, books, videos of different types. By the time, aged nearly sixty, he got to Setting a Good Corner – which came just before his late-career masterpiece Mapping the Studio I (Fat Chance John Cage) (2001) – he had very little to prove. Maybe he’d reached that point in a creative life where the weight of accumulated understanding begins to slide towards a need to give back. Nauman, in this video, is student and teacher at once, good-humouredly sermonising on the necessity of remaining a student. (Even if you’re, say, the greatest living American artist.) He’s not a neophyte, not a gentleman farmer, but someone can help him fine-tune. True for all of us.

Nauman is student and teacher at once, good-humouredly sermonising on the necessity of remaining a student. He’s not a neophyte, not a gentleman farmer, but someone can help him fine-tune. True for all of us

After a while, it’s increasingly rare to have those experiences where something you thought wasn’t art becomes it. Setting a Good Corner does that, around the point – different for every viewer, probably – where you think: ‘My God, he’s really just going to film the emplacing of a fencepost’. That’s what you get, authentically, while watching it, that art can really be anything and that what makes it so is ticklishly anterior to language. It’s only afterwards, when you’re doing something and your mind drifts back to Nauman and Riggins, that the process reverses: that, outside of the museum or gallery, anything can also be treated as a form of artistry, as philosophy. It’s probably easiest to have that association if you are, indeed, laying a fencepost yourself, but if you work in an analogous spirit – easy there, long as it takes, get it right or the next thing won’t be right – you partake of the principle. Now, Setting a Good Corner could of course appear hokey, cowboy wisdom. But it won’t be owned by such a reading, and as such is of a piece with Nauman’s flickering word-based neons, the endless equivocation right there in the relationship between title and subtitle, everyday diluting highbrow, highfalutin elevating mundane. (You think of Glen Baxter’s incongruous cowboys, opening their mouths to opine on Rothko or whatever.) As for precisely why it’s art and not an instruction video, outside of his making it, even Nauman demurs: ‘It’s probably the part that I can’t say’.

The final twist of the corkscrew, though, is this. Nauman, one day in 1999, had some mandatory work to do on his farm, out there in the real world. To make sure he did it right, he took some local advice; and by setting up a video camera, inserting a standard-length, one-hour videotape, looking attentively at what he taped and making a decision, he also got a work out of it. (A big ‘see what I just did?’ flex, another artist might think.) You might say Nauman also got a permanently installed minimalist sculpture out of it, given that he says himself that he saw the corner as beautiful. And the video itself, while seemingly casual and chancy, happens to be wonderfully deadpan, instructive and like a spore that, once ingested, can rise to the surface of the mind anytime the viewer does honest work later, serving to dignify it, smarten it. That’s a magic trick. But it’s Bruce Nauman, so we shouldn’t be too surprised.

Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts runs at Schaulager, Basel, through 26 August, and at MoMA and MoMA PS1, New York, 21 October – 17 March

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview