In his 2013 essay ‘Dub: Red Hot vs Ice Cold’, Richard Skinner describes the emergence of dub music during the 1970s as the encounter of two streams: the warm ‘riddims’ of Jamaican reggae with the icier beats of European and North American metropolises. I was reminded of this confluence by looking at the 15 paintings in Denzil Forrester’s first exhibition at Stephen Friedman, which focuses on his depiction of the London dub and reggae scene of the 80s and 90s. Himself the product of two cultures – having emigrated from Grenada to London with his parents at the age of ten – Forrester was drawn to Hackney’s nightclubs (Four Aces and Phebes, among others) as an art student, sketching the DJs and MCs performing at the makeshift, totemic sound systems and the crowds as they bounced to the rhythm of the bass and swayed back and forth to the flicker of the strobe lights, or just hung around playing dominoes. His resulting canvases, shown across two spaces and a temporary room in the neighbouring, newly built gallery complex, are infused with the energy of a scene experienced and recorded first-hand by Forrester (‘What I used to do was draw to the length of a record – about 3 or 4 minutes… I’d do about 30 or 40 drawings a night’), while serving as a lens onto an important yet little documented subculture.

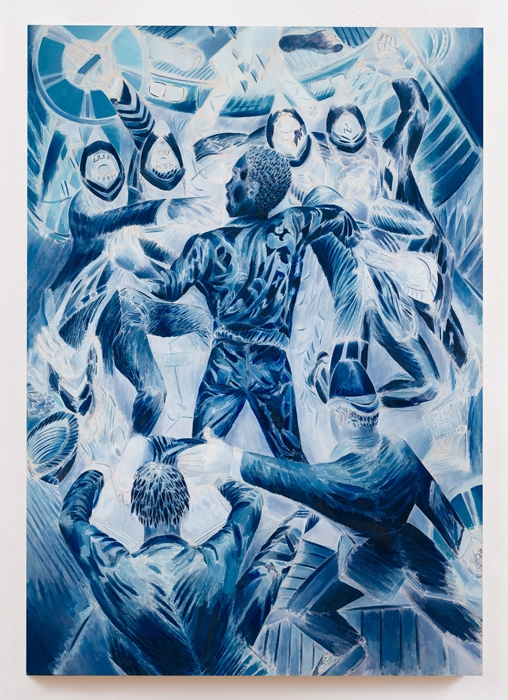

Forrester’s impressionistic use of colours, like Skinner’s dub analogy, oscillates between hot and cold. In the diptych Wolf Singer (1984), the largest painting on view, the green and blue overtones of the background and the dancing musician caught mid-pose (as well as the titular wolf at his feet) are brought into life by a swirl of red and purple defining the people surrounding him: they are dancing or sitting, one holding a book open on his lap. Also structured around a central figure, the blue monochrome Blue Jay (1987) uses a similar composition to more claustrophobic effect by collapsing the perspective. Pictured from behind, it first appears as though Jay is dancing, trancelike, in the midst of a crowd; on closer look, the peripheral figures (one sporting a police uniform) don’t seem to be dancing so much as running towards and threatening him. In which light, Jay’s expressive gestures evoke panic and fear. In the bottom right corner, another open book reads, ‘Buried amongst the dry leaves beneath the forest floor / There to rest in the shade, here lies the Rose’: a reference, we learn from the show’s handout, to the killing of his childhood friend Winston Rose by police in 1981.

These paintings record the physical and cultural spaces in which London’s black British community could converge and escape oppression (police raids during the 1990s led to the closure of most of these clubs). At 63, and now surrounded by the quiet of Cornwall, Forrester continues to paint those scenes, as three recent works attest, using some of his old sketches as basis for the compositions. With the distant light of memory, however, the energy of the original images has faded; the compositions are stiffer, the figures silent; a literal and figurative blue hue has replaced the vibrating contrasts. What remains is the impression of what has been lost.

Denzil Forrester: A Survey at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, 25 April – 29 May 2019

From the Summer 2019 issue of ArtReview