Ties of History: Art in Southeast Asia at Metropolitan Museum of Manila, Vargas Museum and Yuchengco Museum, Manila, through 6 October

Maligayang kaarawan. ‘Flabby, directionless and… looking extremely lethargic and tired.’ Welcome to ArtReview Asia’s autumn previews! Heh, heh, heh… Jokes aside, the borrowed words are T.K. Sabapathy’s verdict on the biennial ASEAN exhibitions and symposiums, launched in 1980. The Singaporean critic was writing on the occasion of the 3rd ASEAN Travelling Exhibition of Painting, Photography and Children’s Art, in 1993 and looking – nervously – forward to where the Association of Southeast Asian Nations might be taking the region’s art in the twenty-first century. ‘Increasingly, the ASEAN exhibitions and symposiums are like cocktail gatherings, filled with pleasantries but impotent and of no consequence,’ he continued, before proposing six actions the event managers could take to increase its potency. Last year marked a key cocktail moment – the 50th anniversary of the founding of ASEAN – and Manila is staging a tripartite exhibition, curated by Patrick D. Flores and titled Ties of History: Art in Southeast Asia, to mark the conclusion of those celebrations. Alongside the usual stuff about mutuality, commonality, regional diversity and neighbourly solidarity, as well as trade, peace, economic growth and an unstated aim of halting the spread of communism, the Bangkok Declaration (the organisation’s founding document, signed by the governments of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand) lists the promotion of Southeast Asian studies as one of ASEAN’s core goals; the association’s first art exhibition was staged in Jakarta one year afterwards. Half a century later, Flores’s contribution takes one artist from each of the ten current ASEAN member states (Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos and Brunei have joined since 1967) and presents an example of their work in each of the exhibition’s three venues. The result is three exhibitions that are the same but different: just the kind of contradictory oneness that a trade confederation like ASEAN is all about. Those artists are Amanda Heng (Singapore), Roberto Feleo (Philippines), Anusapati (Indonesia), Do Hoang Tuong (Vietnam), Chris Chong Chan Fui (Malaysia), Yasmin Jaidin (Brunei), Min Thein Sung (Myanmar), Vuth Lyno (Cambodia), Jedsada Tangtrakulwong (Thailand) and Savanhdary Vongpoothorn (Laos); Flores’s aim is to explore a region and a collection of art practices that is, by necessity, in ‘a condition of constant forming’. Certainly attempts to form the region’s artistic practices into some sort of shape are all the rage with Asia’s art institutions at the moment, if recent exhibitions such as last year’s Sunshower at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo and M+’s current In Search of Southeast Asia in Hong Kong are anything to go by, and there’s no doubt that Southeast Asia offers some of the richest and most intriguing art on the continent right now and is rapidly developing the infrastructure (in the form or public and private art museums) to show it off. Philippine senator Loren Legarda has already stated that she hopes that other ASEAN nations will continue Flores’s project in the form of a biennial exhibition (and acknowledge Manila as the centre of Southeast Asia’s art scene while they are at it). Sabapathy is doubtless sharpening a few pencils, but Flores isn’t one for hanging around and will be the artistic director of the next edition of the great critic’s hometown biennial, which takes place in the city-state next year. In the meantime, those of you who can’t wait for that real biennial fix are spoiled for choice.

12th Gwangju Biennale at various venues, Gwangju, through 11 November

First stop South Korea and the Gwangju Biennale. Last year Sunjung Kim (previously director of Seoul’s influential Artsonje Center) was announced as the new president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation. Her appointment came in the wake of an evolving scandal involving now jailed former South Korean president Park Geun-hye’s administration of a 60-page blacklist of 9,473 cultural figures who were excluded from any kind of government support and funding (Gwangju receives government funds), and consequently marks something of a ‘reset’ for a flagship festival that was founded in 1995 to commemorate the pro-democracy civil uprising of 1980 and its brutal repression by government forces (incidentally the subject of Booker Prize-winning and government-blacklisted novelist Han Kang’s 2014 Human Acts). The 12th edition of the biennial, titled Imagined Borders, features elements – looking at the relations between architecture and nation-building, Southeast Asian migration (you were, of course, expecting that one) and the impact of the Internet, among other things – conceived by no less than 11 curators and academics. In addition, Adrián Villar Rojas, Mike Nelson, Kader Attia and Apichatpong Weerasethakul have been invited to produced new public projects at historic sites throughout the city, while three international organisations – the Palais de Tokyo, Helsinki International Artist Program and Philippine Contemporary Art Network – will produce pavilion projects (in a civic centre, a temple and an art museum respectively), all of which seem designed to spread the biennial’s focus beyond the borders of its traditional home in the bunkerlike Biennial Halls. And, of course, beyond the borders of South Korea too.

Busan Biennale 2018 at Museum of Contemporary Art Busan and the former Bank of Korea building, through 11 November

Still, you will actually have to go there to see it and will probably want to take in another biennial in the port town of Busan while you’re at it. It’s on the other end of a three-hour (or so) bus or car journey from Gwangju. Once there, Paris-based curator Cristina Ricupero (who was involved curatorially in the 2006 Gwangju Biennale) and Berlin-based critic Jörg Heiser will be your artistic directors of an exhibition titled Divided We Stand. Take that, ASEAN! And take this, Gwangju: ‘We think the time of the mega-exhibition, exhausting even the most professional visitor with ever more venues and artworks, is over,’ the dynamic duo state as an opening gambit to their exhibition statement. Their exhibition is going to feature just over 60 artists and focus on the geopolitical and psychological effects of territorial division and secession over the past 70 years or so. Expect Cold War trauma, post-Partition trauma, post-Soviet trauma, post-Yugoslavia trauma, post-9/11 trauma and, somewhere along the way, one presumes, divided-Korea trauma to be addressed. Among those exploring these particular forms of bipolarity will be Yael Bartana, Hsu Chia-Wei, Minouk Lim, Lars von Trier and Ming Wong.

Seoul Mediacity Biennale 2018 at Seoul Museum of Art, through 18 November

Ricupero was also an adviser to the SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016, and you’ll want to head to Seoul next in order to check out the current edition of that fandango (take the TKX, Korea’s fastest train, from Busan and you’ll be there in just under three hours). The first thing you’ll notice is that the event has changed its name and is now the Seoul Mediacity Biennale. The next thing you’ll be aware of is that it’s (controversially) curated by a group of five men (the 2016 edition was devised by an all-women team) drawn from the worlds of dance, literature, environmental protection and economics (that people with expertise in fields other than art are involved is not controversial). And the final thing you’ll remark on is that, until recently, that group used to contain six men, the disappeared member being Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) director Choi Hyo-jun, who is currently suspended following allegations of sexual harassment (which he denies). You’ll have focused on those things because precious little information is available ahead of this biennial, other than the fact that the exhibition is titled A Good Life (which must have sounded like a good idea at the time), that philosophers Aristotle and Ernst Bloch, and novelists Albert Camus and Aldous Huxley will be evoked, that the focus is on a range of media and that the exhibition’s curators are, in somewhat sinister fashion, calling themselves ‘the Collective’. But you’ll remain calm because, as you know by now, collective curating is something that’s happening all over South Korea at the moment.

Francis Alÿs at Art Sonje Center, Seoul, through 4 November

But that’s not to say it’s happening everywhere in South Korea. While the group of 11 are putting together the current iteration of the Gwangju Biennale, Sunjung Kim has popped back to the Artsonje Center to curate a solo exhibition, titled The Logbook of Gibraltar, by Mexico City-based Belgian artist Francis Alÿs. It opens a few days before Gwangju, so don’t get shirty about Kim needing to be in two places at once. Borders and their sociopolitical effects remain the subject here. The two-channel video Don’t Cross the Bridge Before You Get to the River (2008) examines that between Spain and Morocco via groups of children on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar lining up with toy boats made out of shoes and attempting to meet by walking into the water and towards the horizon. In Bridge/Puente (2006), the tension between Cuban migrants and US immigration authorities is the subject matter as a group of fishermen from Havana and Key West line up their boats to create a floating bridge. Elsewhere in the exhibition you’ll find some of the artist’s elegant drawings and a reappearance of those ‘shoeboats’, this time as an installation.

Michael Joo at Art Sonje Center, Seoul, through 14 October

Alongside Alÿs, Artsonje will be hosting another solo exhibition, this one featuring the work of American-Korean Michael Joo. Titled Verfremdungseffekt, which translates from the German as ‘alienation effect’ and is a term originated by Bertolt Brecht in his 1936 essay ‘Alienation Effects in Chinese Acting’ (involving the notion that the audience should be distanced from rather than absorbed into the action and characters on stage), the exhibition is based around a new public artwork (after which the show is titled) commissioned by the Real DMZ Project for the Peace and Culture Plaza in Cheorwon, on the edge of Korea’s demilitarised zone. That installation centres on the collection and displacement of seven natural volcanic boulders around a cast cement work made up of scanned and enlarged fragments of smaller volcanic material collected along the Hantan River. The work itself is inspired by the Seung-il Bridge (you see – that’s the kind of tight connection, with Alÿs as well as the two sides of the river, that curating is all about), which spans the river and is said to have been begun by North Korea in 1948 before being completed by South Korea in 1952. The rock fragments of the central sculpture in Cheorwon were collected by South Korean children and used to play a traditional game (땅따먹기) on the bridge itself, before being scanned and enlarged at a robotic craft workshop. Geological age becomes cultural age becomes technological age. The processes explored to deliver this mix of natural and human displacement form the subject of the exhibition and a new videowork titled Saltation, Traction, Precipitate (2018). At this stage of your trip it’ll be like a second coming of the Busan Biennale: not so flabby now, huh?

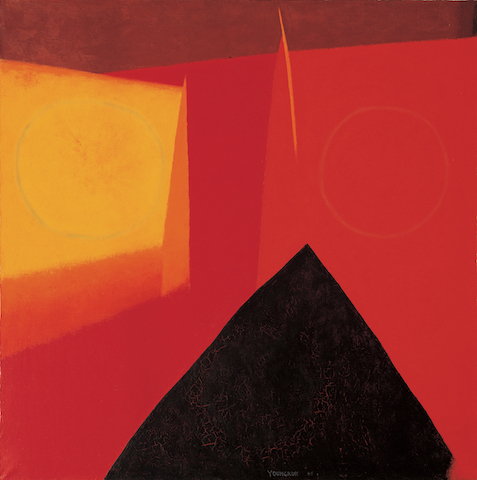

Yoo Youngkuk at Kukje Gallery, Seoul, through 7 October

So let’s ramp it up as we turn to the next stage of your Seoul experience and Korean abstractionist Yoo Youngkuk, who studied art in Tokyo, returned to Korea during the Second World War, made a living as a fisherman and brewer, returned to art during the 1950s, working with a variety of avant-garde groups (among them New Realism and New Figures) before ditching the collective thing (take that, Seoul Mediacity Biennial) in 1964 and working and exhibiting solo until his death in 2002. The abstract landscapes-cum-Colour Field-type paintings (a merging of Eastern and Western traditions) he produced during the latter period are the subject of an exhibition titled Colors from Nature at Seoul’s Kukje Gallery and provide a healthy reminder that there was something other than the now-ubiquitous Dansaekhwa monochrome painting going on in Korea during the second part of the last century.

Norberto Roldan at Silverlens, Manila, through 13 October

While he may not have taken multitasking quite as far as Yoo, Filipino artist Norberto Roldan currently juggles his work as an artist with his role as artistic director of Manila’s longest-running not-for-profit art space, Green Papaya Art Projects in Quezon City. Before all that (and founding the group Black Artists in Asia in 1986, which explored social and political artistic practice), Roldan studied philosophy as an undergraduate, and the title of his latest show at Silverlens – How can you jump over your shadow when you don’t have one anymore? – certainly conjures Martin Heidegger (a 1935 lecture on Immanuel Kant and the limitations of being) and Platonic philosophy, but is more immediately borrowed from Jean Baudrillard’s dedication in Fragments: Cool Memories III, 1991–1995 (1997). The Frenchman has provided the impetus for previous Roldan exhibitions, and you’ll be getting the idea by now that readings of texts generally inform the questions he asks when it comes to the reading of objects and images. And knowing that it is eight years since his last solo exhibition is also to know that he has had plenty of time (other activities allowing) to read. Often deploying a variety of media and materials to create assemblages, Roldan once said that that process ‘builds the context for storytelling without giving the whole story’; so, given that, as an artist, he operates in the slippery territory between objects and meanings, shadows and/or the lack of them should be a subject that’s right up his street.

Part II of previews to follow…

From the Autumn 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia