In what’s become an oft-cited 2013 speech, the then-chairman of the Hong Kong SAR Basic Law Committee, Qiao Xiaoyang, stated that any future heads of HK’s government ‘must be persons who love the country and love Hong Kong’. China, he implied, should be on an emotional par with any feelings for HK itself. In response, three days later the prodemocratic movement that had recently been known as ‘Occupy Central’ added the specification ‘with Love and Peace’ to their full official name. Love, both parties seemed to agree, is definitely the main issue, while also bolstering the truism that the more vague the language and big words getting bandied about, the touchier the subject being discussed. Hong Kong artist Yip Kin Bon has responded to the relentless blather by editing it out altogether. A blocky newspaper rack made out of wood sits in the middle of the gallery, in it five wispy newspaper pages billowing lightly in the wind. Every single word has been obsessively removed from the pages of Blank (2014), leaving precise, delicate strips of space and thin ribbons of remaining paper. Another similarly dissected newspaper page, sitting framed on the wall, has left one phrase across the top: ‘I’m a Hongkonger.’

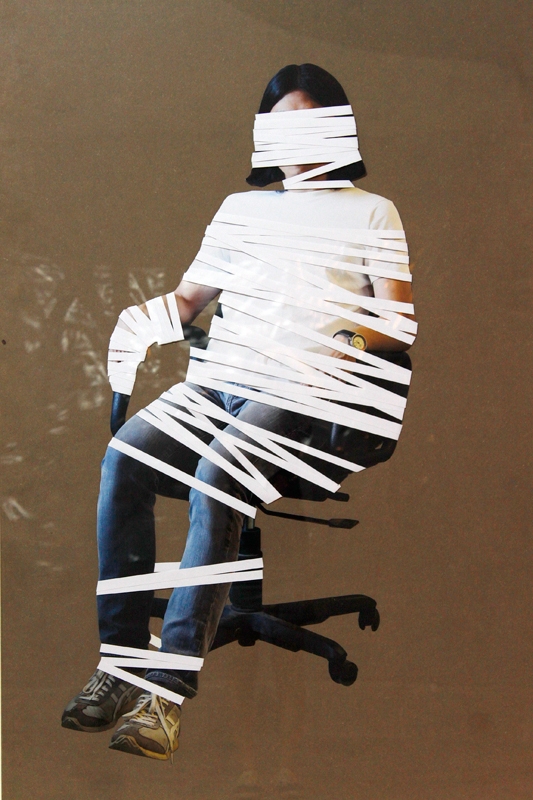

Yip undoubtedly loves his city, but this portrait of his home depicts it as gagged or, like the show’s title, ‘almost black, the white terror / almost white, the black humour’, bound in a nonsense trap. A series of photographic collages titled Stuck in There (2014) captures people on the city’s streets, strips cut from the image filling the outline of their bodies; the effect is as if each is tied up from head to foot, by their own car, or by a shop’s ‘Sale’ signs, or by the city itself. Yip’s method to cut his way out of this, though, only seems to replicate the problem: half of the exhibition is taken up by his interpretation of Qiao’s infamous speech. Speech from Qiao Xiao Yang, 24 March 2013 (2013–14) comprises 250 small newspaper clippings, each held in a small plastic zipper bag. Isolated Cantonese characters from headlines, political figures and the occasional Egg McMuffin dot the two walls, as if, in an attempt to parse the news and its boringly hyperbolic language, Yip has exploded it into fragments and forensically isolated each component.

He doesn’t quite manage to find a new vocabulary, though it becomes a looser, but no less loaded, nonsense, where through the gaps we can at least examine more closely the linguistic trap in which the artist finds his city mired. While the censorial implications of his work are its most obvious connotations (picking up further layers of political melodrama during the show’s run, as the late-September demonstrations spread in Hong Kong and the Chinese media took measures to stop its images spreading over the border), Yip also hints that the double bind is implicit in the ‘Hongkongers’ self-representation, a mundane self-censorship.

This article was first published in the Spring 2015 issue of ArtReview Asia.